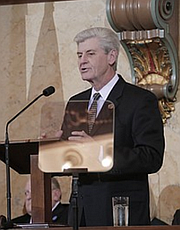

The state’s system of mental-health care is the subject of a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit, which alleges that Mississippi over-relies on institutionalization instead of using community-based services for citizens. Gov. Phil Bryant (pictured) wants to oversee the system himself. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — L.S., now 19 years old, has a dream of becoming a chef, but has cycled in and out of mental and behavioral health institutions throughout his life. As a young teenager, in 2010, he sued then-Gov. Haley Barbour along with several other children in the state to receive the services he needs.

Now, L.S. is aging out of a system that can serve his intellectual disability and mental-health needs. Last week his lawyers argued that consolidating his case with a related lawsuit against the state would jeopardize his access to mental services.

Lydia Wright, a Southern Poverty Law Center attorney, represented L.S. in the courtroom last week. She said he hopes to work in a kitchen someday as well as get his driver's license—both achievable goals, Wright said, if L.S. gets access to help he needs for his intellectual disability and mental-health disorders.

"L.S. needs care; he has been waiting since he was 13 years old ... for community-based services," Wright told U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate on Feb. 10.

Research in the psychology and psychiatry fields show little to no evidence that hospitals and residential treatment centers are effective in helping a person with mental-health needs. A 2015 Cambridge University study found that children raised in institutions "are exposed to extreme psychosocial deprivation," which can lead to behavioral and developmental problems like higher inattention, lower working memory and a higher chance of developing attention deficit disorders.

Group homes, therapy and other services that enable people to stay engaged in their daily lives while receiving treatment, on the other hand, have proved to be beneficial to those who need treatment—as well as more cost-effective.

The Troupe v. Barbour case, as L.S.'s lawsuit is known, was originally a class-action lawsuit against Mississippi's system of mental-health care for youth. Now, it is an individual case on behalf of L.S., who will age out of eligibility for services under Medicaid on Oct. 21, 2018.

Lawyers for L.S. argue that a magistrate judge's decision to consolidate his case with the Department of Justice lawsuit filed against the state for adults seeking mental-health services is harmful to L.S.

Mental Health in the Capitol

The State of Mississippi has been sued twice for its mental health-care system. First in 2010, the Troupe v. Barbour lawsuit addressed the state's over-reliance on institutionalization for kids, then the Department of Justice sued the State in August 2016 for its over-reliance on institutionalization in its adult mental health-care system.

"Every day, hundreds of adults with mental illness are unnecessarily and illegally segregated in Mississippi's state-run psychiatric hospitals or are at serious risk of entering these institution," the DOJ complaint says. "They enter and remain in these isolating institutions because the State of Mississippi has failed to provide them sufficient community-based mental health services."

The attorney general's office tried to fend off the DOJ lawsuit last year, and for the most part has blamed the Legislature for not appropriating additional funds to the department in the 2016 session.

"Last legislative session I called on the governor and legislative leadership to provide DMH with an additional $12 million to keep us from getting sued, but they instead refused to provide the additional $12 million and cut the DMH budget by $8 million. We were promptly sued," an op-ed from Attorney General Jim Hood says.

This legislative session, in a last-minute change, Sen. Buck Clarke, R-Hollandale, brought up a bill that he said would help the state deal with both mental-health lawsuits. Senate Bill 2567 would have made the Mississippi Department of Mental Health an executive agency, with the governor in charge of appointing the executive director instead of the state board of mental health.

Sen. Clarke gave several reasons why senators should support the bill, including pay raises the board approved for those in management. Clarke said putting the agency under the governor's direction would provide the necessary "oversight."

"I think it's just having the governor's oversight over their budgets and their direction ... if we're trying to comply with the DOJ to go from this institutional care that they had a problem with and go more community-based, that's going to cost money, and we're going to (have to) close down large hospital facilities and move people out," Clarke told reporters after the bill passed the Senate by two votes.

The bill was held on a motion to reconsider, however, and some senators changed their initial votes on Feb. 13, and the Senate killed the bill by three votes.

The Board of Mental Health, whose members the governor appoints, vehemently opposed the bill that essentially benches the board making them advisory in nature only. Its chairman, Richard Barry, explained his issues with the bill in a letter in a letter. "The purpose of having a board is to avoid political interference, provide continuity of quality care and professional oversight of services," Barry wrote in a letter opposing Senate Bill 2567.

Gov. Phil Bryant wrote an op-ed on Feb. 3, published in The Clarion-Ledger, warning that the state's mental health-care system is still potentially ripe for a federal takeover.

"Nothing within the governing structure or state law requires the executive director (of DMH) to report to the governor's office or any other elected official. That is troublesome," Bryant wrote Feb. 3.

"Clearly, something must change if we are to fulfill our moral obligation to those fighting mental illness and their families. Doing nothing will only embolden the status quo and leave those in the care of MDMH further behind." The Secret Report

On the Senate floor, Sen. Clarke mentioned a report, which the public or press do not have access to, called the TAC report, which likely provides the clearest and most accurate snapshot of Mississippi's mental-health services. The State asked a circuit court to put the report under a protective order back in 2015, when they were negotiating with DOJ, trying to fend off litigation. Clarke told senators last week that the report suggests that Mississippi put DMH under the governor's control. He explained the report further on Feb. 13.

"(The report has) been made available to the Legislature to look at ... because it could be pertinent to the appropriations process and it may be (used for) changing our funding models to better help the Department of Mental Health," Clarke told the Senate on Feb. 13. "It's my understanding ... that the issue with the Department of Justice is institutional care versus community-based and the model Mississippi has been following all these years is not what the DOJ would like—thus the lawsuit."

Sen. Hob Bryan, D-Amory, who led the initial charge against the bill last week, said he had not seen statements from the Department of Justice claiming it supported SB 2567 or the report.

"I would certainly like to read (it)," Bryan said. "The difficulty here is once again we are asked to make a decision with long-ranging implications without the knowledge we need to make that decision."

Sen. Tommy Gollott, R-Biloxi, who serves on the PEER Committee, asked the Senate to kill the bill so that the oversight group could look into the situation and report back to the Legislature next year. Senators killed the bill by three votes Feb. 13; in the meantime, the U.S. district court could decide to make the TAC report public.

The Clarion-Ledger initially sued to see the report back in 2015, and the fight for the TAC report to be made public continued last Friday in court. Leonard Van Slyke, representing that newspaper, told Judge Wingate that the Hinds County Circuit Court erred in entering a protective order on the study. Van Slyke pointed out that the report is likely one of the only documents that "gives us the real facts in the case" and also said that all participants in the study were told and were aware that it would be made public.

The state's original defense for concealing the report was the ongoing negotiations with DOJ before they sued last August.

Jim Shelson, an attorney representing the State of Mississippi, asked Judge Wingate to uphold the magistrate judge's ruling on the TAC report, saying the report was created and exchanged for the purposes of negotiations between the state and the Department of Justice. He argued in a brief Monday that the report could not be admitted as evidence in the case.

Editorial: Stop the Mental Health Politicking

The JFP Editorial Board calls for state lawmakers to stop politics with Mississippi residents' lives.

Troupe v. Barbour and the DOJ's August lawsuit were combined back in December 2016. On Feb. 10, lawyers representing the state asked Judge Wingate to keep the two cases consolidated, saying that both center around de-institutionalization for the state. Shelson argued that seeking unspecified relief for L.S. alone was not necessarily possible especially if community-based services are at the heart of that relief. "Relief as to one is relief to all ... effects (of de-institutionalization) cannot be confined to L.S...they can't single him out for those services," Shelson argued Feb. 10.

Wright argued that to keep the cases consolidated would likely mean L.S. would age out of Medicaid eligibility for services by the time the DOJ case went to court. Shelson said it was impossible to tell how long discovery would take in the case—and pointed out that now that L.S.'s case was individual, a settlement could be reached separately without de-consolidating the two cases.

Wright disagreed.

"The prejudice is 110 percent on the back of L.S. who is 19 years old and right now sitting in a facility waiting for services," Wright said.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter @arielle_amara.