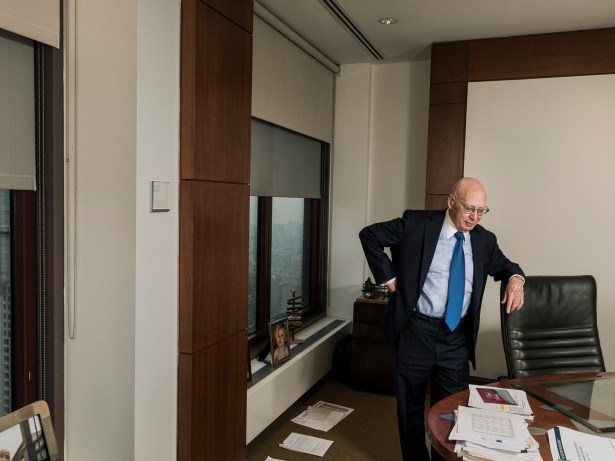

From Developing to Debt Brokering, Richard Bassuk Has Done It All

By Danielle Balbi and Cathy Cunningham February 8, 2017 9:00 am

reprints

Before we began interviewing Richard Bassuk at his West 57th Street office in mid-January, he said, “Firstly, I have a longer history than many of the people who you interview. And as my wife sometimes says, ‘If you live long enough, you get experience in lots of things.’ ”

So far, his wife of 52 years, Eslyn, has been right. The 76-year-old Bassuk recounted to us how he started out practicing tax law and wound up at Starrett Housing developing apartments in Iran—right before the late-1970s revolution that turned the nation from American ally to enemy. Afterward, he left the principal side of the business and formed The Singer & Bassuk Organization with Andy Singer. Five years ago, the two friends parted ways and Bassuk joined Greystone’s Stephen Rosenberg in creating the Greystone Bassuk Group.

Now, as the co-chairman and chief executive officer of the advisory firm, Bassuk has pushed the company’s reach far past debt placement. In just the last few years, Bassuk, a father of two sons and grandfather of two girls, has brought on Paul Fried from L&L Holding Company to head up equity placement and Allison Berman from Katten Muchin Rosenmann to oversee the firm’s EB-5 regional center. They’re expanding on the impressive Rolodex he and his colleagues have amassed over the years, which includes major New York City players such as BLDG Management, L+M Development Partners, RXR Realty and Taconic Investment Partners.

Commercial Observer: Where did you grow up?

Bassuk: I was born in Brooklyn. I moved to Great Neck when I was 8 or 9. I went to The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. I thought I wanted to be in accounting and finance. After going through school, I quickly decided I didn’t want to do that, and so I went on to law school. I went to Harvard [University].

While I was at The Wharton School, I started a broker-dealer firm [Bassuk Mutual Service Corp., buying and selling securities]. When I graduated from Harvard—between recruiting people from Wharton and Harvard—I had about 300 people working for me.

How old were you at the time?

Twenty-three.

Jeez. What are we doing?

It sounds better than it really is. But it was really very good. In my [second or third] year at Harvard, I had worked for one of the big Wall Street firms—Franklin Roosevelt’s firm, Carter Ledyard—we represented American Express and all the major brokerages. Carter Ledyard has since lost a lot of its steam, but in those days it was really a very interesting place to be. I went back to Carter Ledyard when I graduated from law school [keeping his broker-dealer firm], and my deal with them was that I would only come back if I could practice tax law. That was one of the most foolish things that anybody could possibly do.

Why did tax law appeal to you in the first place?

I thought that to really get to the heart of business transactions, if you understand the tax side, you’ll really have a very good insight into how everything works. That was generally true. So I practiced tax law. I went for my Masters in taxation. I ran my broker dealership, which at that time was doing extremely well. In fact, in the New York area, we were one of the major producers of mutual fund sales. While I was doing that, I was approached by Stanley Egener, who had been the No. 1 mutual fund manager the year before and ran the OppenheimerFund, and his partner, Archer Scherl, who had been representing my broker dealership. They asked me if I wanted to start a mutual fund advisory company with them. I gave it the amount of thought that was justified—about five and a half seconds—before saying yes. But I had to do two things: I had to stop practicing law, and I had to sell my broker dealership because it would have been a conflict of interest.

We started a fund called the Side Fund. In 1971, we sold it to Neuberger Berman. My partner went over and became the president of all their mutual funds. I decided that I wanted to change fields. I thought mutual funds would have a very difficult time—boy, was that another bad call—so I decided I would go into the real estate business.

Your grandfather, Jacob Bassuk, was in real estate, correct?

My grandfather [and other members of my] family had been involved in real estate. And I thought with the bundle of characteristics and knowledge I had developed, that it would be a good place to be. In fact, it turns out that I was right.

I went to a company called Starrett Housing in 1973. Six years later I became the president of the company. I accounted for probably in that interim period maybe 70 or 80 percent of the net profits because I ran the development business, and at that time, in 1974, Starrett decided to build in Iran. Why Iran? Because people came to us and said there’s an opportunity there: No one had good housing. So we did a market study and looked at how many people had Mercedes and BMWs. In Tehran, there were 50,000-some-odd people who had those, and there was no housing of any consequence in the city.

Starrett had built the Empire State Building, so [when we opened up a sales office] I put a big Empire State Building [model] outside the sales door. And the Iranians came. People lined up around the block with bags of cash [literally]. In your lifetime you see things that are hard to believe. When you feel the energy that goes on in these kinds of cases, it’s terrific.

Were you building luxury condominiums?

We did. We built 14,000 units for the Iranian government, of which we had no investment. We built 1,600 condos in eight different buildings for the Iranian people—people who owned places in the bazaar, the professionals. It was the place to be in Iran.

Interestingly, in Iran, the Israelis were very close to the Shah. They were his bodyguards. Starrett had been a Jewish firm, and they came to me and said, “You know, you better be careful. We hear that there are things that are happening in the government which are not going to be good.” Now, I had moved 500 American families over there. We had almost 3,000 people working on the site—it was a huge project. So when I heard that, I went to see the U.S. ambassador and said, “Listen, I’m not going to do anything precipitous. I want to just talk to you about what I’ve heard.” I told him I heard that the Shah was going to be deposed. He said, “Forget it! Not happening. No, not something of that sort.”

I didn’t believe it, so we started moving our families out, but we kept our office open. When the revolution came, they encircled our office. They turned off the water. They turned off the heat. They turned off the electric. And I’m sitting in New York—in those days you had telexes—and they’re telexing back and forth, “What should we do?” I said, “Do what you need to do to take care of yourselves.” They took our people at gunpoint down to the hanging square in Tehran.

Now the story has a happy twist. Earlier, when the Shah was in power, we had been infiltrated by his secret police, the Savak. But I knew that. And when I called meetings I would put radios around the circumference of our meeting room to try to drown out anyone who was trying [to record our conversation]. What happened was that [Ruhollah] Khomeini’s people had also infiltrated us, and so when they took our people down to the square, the people who had been infiltrating us stepped forward and said to one of the Ayatollahs, “These are good people. They’ve brought technology here. They’ve taught us all kinds of things. They’ve brought wonderful housing. They haven’t bribed anyone. They are really the best. Give them back their passports and we will stand in their place.” That’s a pretty remarkable thing for people to say. We took our people out to Greece, and then we negotiated with the Iranian government. They invited us to come back and continue. When the hostages were taken [in 1979] we of course then had to take everyone out. That movie Argo was so much like it.

[Later on], in 1986, Starrett had built the first 80/20, [called Manhattan Park], in New York on Roosevelt Island, 1,100 units, 880 market-rate, 220 low-income. And like everything else, we learned the ropes. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority was supposed to put a subway station on the island, and it was supposed to be there two years before we finished. It came two years after. We had very little way of getting people to the island except for the tram. So we defaulted on what was then the largest Federal Housing Authority mortgage in the country.

How much was that for?

$160 million roughly. Today, it would be peanuts, but back then….

Someone told me, “There’s a person who can help you. It’s a person who operates out of a little retail strip in Virginia. The person’s name is Stephen Rosenberg.” Steve Rosenberg today is the chairman of Greystone and has built that one-man company to 7,500 people. Stephen came, we worked together, we became very good friends and we stayed very good friends.

How did you end up joint venturing with him?

Life is a fortuity. You never quite know what causes different things.

I decided I wanted to buy Starrett. I couldn’t make a deal with the owners so I left in 1994. I then formed a [The Singer & Bassuk Organization] with my good friend Andy Singer. He had been Starrett’s mortgage broker in deals. He had said to me, “Richard, you’ve been a principal all your life. Why don’t you come over and see how you like being on the agency side of the business?” I said, “I don’t know whether I could stand it.” When you’re used to making your own decisions, you then still want to be in a position where that’s the case. But I said, “Andy, let’s do this.”

Andy is a very smart guy and we’re still very good friends. I found it much easier to be a representative of someone in a case than it is to be a principal. On the other hand, personality-wise and outlook-wise, I had a different view of how things were done. If you grow up as being a principal, it’s very hard to just say, “Yes sir.” I didn’t. So I started with different clients and I knew construction. I knew development. I knew management. I knew the sales side. And so people would come. I became part of their team.

I got to a point where my eyesight got very bad. And doing several billion dollars a year [in business], I did it with two people besides myself. When my eyesight became bad—now it’s good, it’s been fixed—I needed to [hire] more people because I just couldn’t handle what had to be done. I said to Andy that we have to move [to a bigger space]. He said, “You know, Scott and I really don’t want to have to move.” That was week one. Week two, I’m having lunch with Stephen Rosenberg, and I’m telling Stephen about the problem I’m having with my eyes. He says to me, “Richard, you have undoubtedly the best clients of any person I know in New York. You have a track record—which I don’t know anyone who has a better one. Why don’t we joint venture?” And I did it. That was five years ago.

Do you think you’ve inherited any of your grandfather’s traits in terms of your work ethic?

Probably. I work very hard at what I do. My wife says I work too hard. But you know what, when you love what you do, you get into it. Nothing just happens. You have to go and you have to make it happen. It’s the nature of business. It’s the nature of politics. It’s the nature of human relationships. And if you don’t do it, you lose something. Or at least I would lose something. That’s all part and parcel of what we do now.

What made your grandfather move here in the first place?

Probably a pogrom in Russia. Trying to flee. It’s a story you hear again and again, and it’s one of the things that really has contributed to the flourishing of our country. People say, “We don’t want to have people who are different.” But there’s energy and strength that comes from having people who want to make their mark. If they don’t do it, their kids will do it, or their grandkids will do it. And that’s unique. I don’t think there’s any other country in the world that has that kind of thing.

My grandfather came over to this country when he was 12, with just the shirt on his back. He became a buttonhole maker, and then a tailor. Then he went into insurance and then he started buying real estate during the Depression. And he assembled a whole portfolio. He was terrific.

During World War II, your family was involved in bringing families over to the United States, right?

When World War II came in 1939 and 1940, my grandfather had already developed his real estate business and my uncle had a chain of furniture stores. To get a family over from Europe in those days, you had to vouch for them. You had to say they had a place to live and had a place to work. What they did is set up their own little operation to bring these people over [where they’d work in the furniture store and live in his grandfather’s buildings]. Together, they brought over several hundred families. That’s something I tell to my sons and I tell it to my two little tiny granddaughters, who are 5 and 6. I don’t know how much of it resonates, but you never know. Children remember certain things. I want them to think about what they can do for people, how the world works and how to be a good human being.