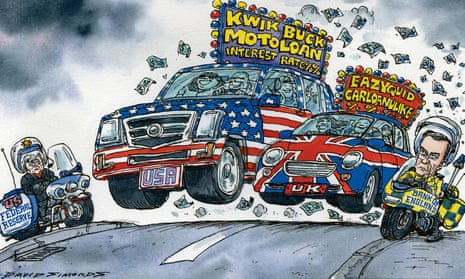

Could it be 2005 and 2006 all over again? Industry figures last week showed that UK credit-card debt has soared while the savings rate has plunged to an all-time low. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, data shows that late last year car loans were being taken out at a faster rate than any time in US history.

Almost everyone in America leases a car or buys it using cheap credit. Except that they don’t take the opportunity to lower their outgoings and cut their monthly loan bills. Instead, they take the cheap credit and buy a bigger car. A much bigger car.

This applies as much to those on low incomes as the wealthy. And the same trend can be seen in the UK.

In 2008 it was the mortgage sector in the US that triggered the worst global financial crash since 1929. US house buyers on low incomes were sold homes by lenders using teaser rates that offered massive discounts for two or three years on standard fixed rates. Refinancing was easy as long as the base rate remained low.

Once the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates, it become financially crippling to refinance a mortgage and arrears began to creep upwards.

By 2006, millions of American families were in financial trouble and by 2008 hundreds of thousands were handing the keys of their homes back, leaving the banks with huge debts on their balance sheets.

Today the US central bank is again raising interest rates, and the jump in credit costs is hitting the finances of low-income families, forcing them into arrears or to default on their loans.

But the situation is very different to 2008 and even the years leading up to it. Car loans are an important component of the credit market, but are still dwarfed by home loans. As such, it is unlikely that dodgy car-loan books will see the big lenders getting themselves in such deep trouble.

The lenders, and especially the big banks, have much bigger reserves, giving them deeper pockets when the times comes to cover their losses.

The regulators are also alive to a problem they blatantly ignored ahead of the last crash.

Last November, the New York Federal Reserve bank warned that arrears in the sub-prime car-loan sector were a “significant concern”. The Bank of England has also voiced concern about rising household debts levels and last week promised a review of banks’ lending standards.

It is likely that the cause of the next crash will come from a dark corner of the financial services industry that regulators believe is insignificant until it whacks them on the nose. But, at least for now, they are not the complacent animals of yesteryear and will snap at the big financial firms to keep their practices in order.

Another detail from 2008 that is absent in 2017 is the role of credit agencies, which ranked the worst sub-prime loans as triple-A in 2005 and 2006. These days the regulators have more realistic data to hand.

There are also quirks in the official figures that give a false picture of consumers’ financial position. For instance, the official figures show a collapse in the savings rate is to a significant degree the result of pension funds switching funds out of risky assets and into safer ones following the Brexit vote.

This depresses the incomes of pensioners’ funds and drags down the savings rate, but is a technical issue and doesn’t indicate that pensioners are on a spree, suddenly spending all their savings.

Nonetheless, the regulators need to remain vigilant. Even low rates of default can ripple through the financial system. And should a crash be avoided in the UK, it could still happen in the US, where a Donald Trump inspired credit boom is predicted by many – with an accompanying hangover.

An air war over Europe?

Of all the warnings that pro-Brexit voters chose to ignore last June, the notion that planes might cease to link this island to the continent barely figured on the Project Fear register. Nine months on, with the pound depressed, food prices up, and article 50 triggered, it might be worth hesitating a little longer when Ryanair repeats that there is a “distinct possibility of no flights” for a period when Brexit happens.

Of course, Europe’s biggest airline has form when it comes to courting publicity, and many of its chief executive’s wider views on politics come across as headline-hunting exercises. But the Irish airline has a finely tuned sense for aviation agreements, and an ear for blarney, through its disputes with the European commission and its navigation of local employment and taxation laws. So it is worth noting that it has not been impressed by the Department for Exiting the EU’s promises to prioritise airlines’ concerns.

The clock is ticking on Britain’s two-year separation, but as Ryanair points out, its own flight schedules need to be fixed a year before that, effectively doubling the speed of Britain’s dash into turbulence. And many of Britain’s international flying rights do not exist outside the EU: there is no fallback agreement.

The idea of grounded planes sounds preposterous to British ears; less so to continental airlines and governments, which might appreciate a new competitive advantage. More likely is that in 12 months’ time Britain will face either the further relocation of Ryanair routes – and some of easyJet’s – or have to accept Europe’s terms for associate membership of its common aviation area.

However, with flights to Europe accounting for two-thirds of all UK air traffic, March 2019 could bring plane-free skies not seen since Eyjafjallajökull exhaled its ash in 2010. Such a scenario remains unlikely, because surely a deal will be reached. But the very possibility will make Remainers shake their heads in wonder. Britain has the largest aviation industry in Europe, and to preserve it, ministers must now beg and wheedle to reclaim its rights, which they have just signed away.

A mission impossible for Paramount boss?

Don’t envy Jim Gianopulos, the new head of Paramount Pictures. Running a Hollywood studio remains a glamorous job, but amid the premieres and parties the challenges are piling up.

The US film industry is threatened by the rise of the Netflix-led streaming companies, by rampant piracy and by the popularity of alternative distractions, such as gaming and social media.

Then there are obstacles specific to Paramount and its lowly competitor Sony. It is very difficult competing with big hitters like Disney – owner of the Star Wars and Marvel Comics franchises – and Warner Bros, the studio behind the Harry Potter universe, and both studio minnows also have struggling parent groups.

Gianopulos has some decent properties at his disposal, including the Mission: Impossible series, but he has to take one decision for the greater cultural good. Please, Jim, let the latest Transformers film – due for release in June – be the last.