The reign of Louis XVI, the final Bourbon king of France, was a varied and eventful one, but when we think of him and his queen Marie Antoinette, certain associations inevitably pop into our minds. Perhaps we think of the couple’s ostentatious wealth, as exemplified by their palace at Versailles. Or, maybe we recall their blasé attitude towards the working poor, as reflected in Marie Antoinette’s famous quip, “Let them eat cake.” Some of us may think immediately of the grim machine responsible for the royal couple’s untimely end, the guillotine.

This historical shorthand may be the best we can do when we’re trying to absorb the whole of human history, but it doesn’t present us with a very well-rounded picture of an era or its important actors. In fact, sometimes it doesn’t deliver a very accurate picture at all. For instance, Marie Antoinette, forever identified with the contemptuous phrase “Let them eat cake,” never actually spoke those words. Yet, this tidbit of misinformation has defined her for generations.

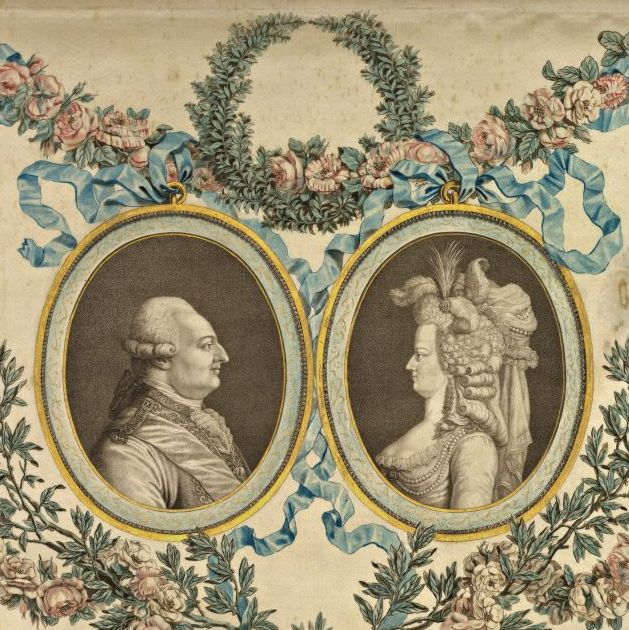

History is made by people – people who have likes and dislikes, who love and hate, who possess virtues as well as flaws. Kings and queens, living on a large stage, experience more spectacular successes and more dramatic failures than most of us, but ultimately they are just people. Today, on the anniversary of King Louis XVI's execution in 1793, we spotlight some facts about him and his wife Marie Antoinette that may help to add a human dimension to our understanding of these often maligned historical figures.

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were barely in their teens when they married

In the days of the European monarchies, marriage was less a matter of personal inclination than political expediency. Governments interested in forming alliances with other countries would as a matter of course attempt to unite their leaders with the offspring of other royalty. This was the case for Louis-Auguste, third son of the dauphin of France, grandson of King Louis XV.

Louis-Auguste was not a promising specimen. His grandfather, the king, considered him “ungainly” and “dimwitted”; kinder appraisers regarded him as shy and withdrawn, living in the shadow of an attractive older brother being groomed for the crown. This brother died young, however, and Louis-Auguste the loner was thrust into a public role as the heir apparent to the throne.

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna was born in Vienna, the beautiful daughter of Emperor Francis I. Unlike Louis-Auguste, who had a rather austere upbringing, she was a very social child with a close family and many friends. She liked playing music and dancing and was reportedly very talented at both. Her mother Maria Theresa, acting as queen after the death of the emperor, planned to unite Austria with its former enemy France through marriage. Most likely, Antonia would not have been selected to fulfill this duty, but her older, eligible sisters had died from an outbreak of smallpox. Not yet 12 years old, she was promised to the future king of France.

Marriages often took place by proxy in those days; Maria Antonia was married to Louis in 1768, without having met him (her brother stood in). In 1770, she was finally sent to France for the formal marriage ceremony. She was 14 at the time, Louis was 15. On the big day, Louis donned a suit of silver, and Marie wore a lilac dress dripping with diamonds and pearls. There were over 5,000 guests, and a crowd of 200,000 watched the concluding fireworks display. Two occurrences of that day could be seen as bad omens for the marriage: a big storm, which threatened ominously during the ceremony, and a riot at the fireworks display that resulted in hundreds of people getting trampled.

Louis and Marie’s royal bedroom was on the quiet side

Since they were more or less children at the time, we would not be surprised today that nothing much happened at first when Louis and Marie were thrust together. One of the key reasons for royal marriages, however, was to produce heirs, and this was expected to happen with some alacrity. In the case of the royal couple, a long night stretched into seven years, a situation that not only personally distressed the members of the royal household, but which in time became a political liability.

Several reasons have been proposed for the fact that the marriage went unconsummated for seven years. Louis, self-conscious and insecure, may not have been very interested in sex, unlike his licentious grandfather, who lambasted him for his reluctance. Marie, who was interested in sex, became increasingly frustrated with this state of affairs. Her mother eventually sent Marie’s brother Joseph to town to find out what the problem was. Joseph referred to the royals as “two complete blunderers” and didn’t discover any good reason why the sheets remained so cold in the royal bedchamber other than a lack of inclination or, perhaps, a lack of education.

Joseph’s straight talk during his visit seemed to produce results; the couple sent him a thank-you letter and produced four children in relatively quick succession. Some wags wondered if the children were Louis’s, given Marie’s almost understandable interest in other men at court, but no one was able to prove otherwise. The long delay had done damage to Louis’ reputation as king, however, with some critics contending that a man who could not perform on a personal level was likely to be just as ineffective as a leader. Some ill-advised policies advanced by Louis did nothing to contradict this point of view.

Louis spent more time on padlocks than wedlock

Since Louis didn’t seem very interested in a vivacious young bride, what exactly was he interested in? Although it wasn’t the kind of working with his hands that the French may have preferred, what Louis liked to do was work with metal and wood.

Unencumbered with learning how to be kingly at a young age, Louis found himself drawn to the solitary pursuits of lock making and carpentry. The royal locksmith, a man named François Gamain, befriended him and taught him how to make locks from scratch. It wasn’t long before Louis became interested in carpentry and began to make furniture. If his path in life hadn’t been preordained, it seems likely that Louis would have been a simple craftsman rather than a king. On the other hand, being king allowed Louis to explore his interests on an extravagant level, given that the palace at Versailles was his playground.

Once, Louis attempted to use his talents to reach out to his wife. He crafted her a spinning wheel, a considerate present for a clotheshorse like Marie Antoinette, who averaged over 200 new dresses per year. The story goes that Marie thanked him courteously and then gave it away to one of her attendants.

Later on, Louis had much worse luck with his old friend from the locksmith shop. Nervous about the revolutionary fervor bubbling up in France, Louis asked Gamain to craft an iron chest with a special lock to protect important papers. By this time, Gamain had secretly joined the revolutionary cause. Marie warned Louis that Gamain might be untrustworthy, but Louis could not believe that his friend of 20 years would betray him. He did, and the betrayal led to the discovery of the iron chest by the ministers seeking to overthrow the king.

Marie Antoinette liked flowers and chocolates, Queen-style

While Louis was busy making locks and spinning wheels, Marie was indulging her taste for luxury. Raised by her family in a homespun manner, often helping out with chores and playing with “common” children, Marie nonetheless took to the role of queen with gusto. She became notorious for her pricey fashions and expensively sculpted hair. A party girl, she planned and attended innumerable dances, once famously playing a trick on her homebody husband to get out the door sooner. Louis usually went to bed at 11 p.m., so the mischievous Marie set the clocks back so that he went to bed earlier without realizing it.

Two of Marie’s favorite things were, ironically enough, things we associate with romance: flowers and chocolate. Flowers were almost an obsession with the queen, who papered her walls with flowered wallpaper, decorated all of her commissioned furniture with flower motifs (perhaps Louis should have put a daisy or two on that spinning wheel), and tended the real thing in her own personal flower garden on her mini-estate at Versailles, Petit Trianon. She even commissioned a unique perfume, whose floral sent was a mixture of orange blossom, jasmine, iris, and rose. (Some historians have contended that this unique scent aided in the capture of the king and queen when they tried to flee to Austria during the height of the revolution.)

As for chocolate, Marie had her own chocolate maker on the premises at Versailles. Her favorite form of chocolate was in liquid form; she’d begin every day with a hot cup of chocolate with whipped cream, often enhanced by orange blossom. A special tea set was dedicated to the purpose. Chocolate was still largely a luxury item in 18th century France, so a steady diet of chocolate was the kind of luxury only available to a queen. Such personal indulgences no doubt added fire to the ire of the revolutionaries.

Louis was a homebody and a bookworm

As the story about the clock makes clear, Louis was not exactly a party animal. While Marie enjoyed music, dancing, and gambling, Louis’ idea of a pleasant evening was to enjoy a good book by the fireside and retire early. Louis XVI had one of the most impressive personal libraries of his day, almost 8,000 carefully arranged volumes of bound leather. Unlike Marie, whose education was spotty, Louis was well-educated and continued to be interested in learning once he became king. Although he no doubt read the philosophy and political thinking that was current, he was a big fan of history and even read fiction. Robinson Crusoe was one of his favorite fictional works. The choice is not that surprising for a man who probably wished he were on a desert island at times.

Louis’s extensive reading fostered enlightened aims. He advocated the abolition of serfdom, an increase in religious tolerance, and fewer taxes on the poor. He supported the American Revolution, hoping to weaken the British Empire. However, these aims were blocked at every juncture by a hostile aristocracy desperate to preserve the social structure in France and irritated that their money was funding foreign wars. A frustrated populace soon blamed the king and the nobility for inaction and revolutionary attitudes began to foment. For a king who tried very hard to be popular and fair, asserting more than once that he “wanted to be loved” by the people, this development was dismaying.

Marie Antoinette was not the monster as portrayed in the media

Political pamphleteers of the day did much to deride Marie Antoinette for her profligate spending habits, nicknaming her “Madame Déficit.” They often portrayed her as an ignorant woman who treated her social inferiors with disregard at best and contempt at worst. Much of this character assassination was simply invented. Although Marie Antoinette was guilty of sins against decorum and exhibited a certain insensitivity to the value of money, she was a person who liked people and bore little resemblance to the cold villain portrayed by her detractors.

Marie was especially fond of children, possibly because she had been childless for so long, and she adopted a number of children during her reign. When one of her maids died, Marie adopted the woman’s orphaned daughter, who became a companion to Marie’s own first daughter. Similarly, when an usher and his wife died suddenly, Marie adopted the three children, paying for two girls to enter a convent while the third became a companion for her son Louis-Charles. Most strikingly, she baptized and took into her care a Senegalese boy presented to her as a gift, who normally would have been pressed into service.

Other examples of her kindness abound. Out for a carriage ride, one of her attendants accidentally ran over a winegrower in the field. Marie Antoinette flew out of the carriage to attend personally to the hurt man. She paid for his care and supported his family until he was able to work again. It wasn’t the first time she and Louis picked up the bill; they even took financial care of the families hurt in the stampede on their wedding day.

Together with Louis, Marie gave liberally to charity. She established a home for unwed mothers; patronized the Maison Philanthropique, a society for the aged, widowed, and blind; and made frequent visits to poor families, giving them food and money. During the famine of 1787, she sold the royal flatware to provide grain for struggling families, and the royal family ate cheaper grain so there would be more food to go around.

All of this is not to say that Marie Antoinette was not a spendthrift who wasted millions of dollars on unnecessary luxuries, but she was also capable of a Christian kindness that her enemies chose to ignore.

Louis XVI was not a cat person

Although he was generally a fair and gentle man, Louis XVI did bear some hatred in his heart for one particular race of creatures: cats.

It’s anyone’s guess where this hatred stemmed from, but a likely source would be his grandfather, Louis XV, who adored cats. Affection was an absent commodity between Louis and his grandfather, and he was unlikely to share enthusiasm for anything that his grandfather loved. Furthermore, Louis XV had allowed his cats to breed indiscriminately, and they overran the grounds at Versailles. There are stories that Louis-Auguste may have been scratched by one of these cats as a child.

Aside from lock making and reading, one of Louis’s greatest passions was hunting. When not pursuing animals in the field, he would often hunt and shoot the cats overrunning the Versailles grounds. Once he accidentally shot a female courtier’s cat, thinking it was one of the feral Versailles cats. He apologized profusely and bought the woman a new one.

It should be noted in Louis’s defense that household cats were not as common in the 18th century as they are now, and his distaste for them was not unusual. For centuries, cats had been regarded as somewhat evil creatures in Europe, and during religious times of the year, they were regularly rounded up, tortured, and killed. At Metz, near France’s northeastern border, “Cat Wednesday” was a Lenten tradition in which 13 cats in a cage were burned alive in front of a cheering crowd. This tradition came to an end during Louis’s lifetime. It’s unlikely that Louis would have tortured cats; he just didn’t seem to want them in his house. Luckily, his wife preferred dogs.

Marie Antoinette was an unhappy victim of pornographers

Always somewhat unpopular in France owing to her provenance (the French and Austrians had disliked each other for hundreds of years), Marie Antoinette was one of the most attacked public figures in the history of France. Often, the attacks on her took on a very unwholesome hue. Even before revolutionary fervor took hold of the country, pamphleteers published satirical, often obscene libelles intended to smear the Queen’s reputation.

The childlessness of the royal couple was no doubt responsible for the initial attacks, which focused just as frequently on Louis. As time went on, however, speculations about the Queen’s love life independent of her husband became rife. At various times, Marie was accused of sleeping with her brother-in-law, generals of the army, other women (apparently, women of Austrian background were considered by many French to be inclined towards lesbianism), and even her son. Marie became a scapegoat for the nation’s ills, her alleged moral failings representative of the monarchy’s evidently debauched character. For pornographic publishers, vilifying the queen while also engaging in cheap (and profitable) titillation was a win-win situation.

All of this slander would be so much hot air if it didn’t have real-life consequences. One of the most troubling is the fate of Marie’s close friend, the Princess de Lamballe, who was superintendent of the royal household. Scurrilous publications had depicted the princess as the queen’s lesbian lover, and public sentiment was against her. After a show trial, she was marched into the streets and attacked by a violent mob. Some accounts mention mutilation and sexual violation as part of the attack, although these accounts have been disputed; what is not disputed is that she was beaten and beheaded, her head stuck on a pike and marched around Paris. Some accounts say that the head was tauntingly raised up so that Marie could view it from her cell in the Temple tower, where she was imprisoned.

Although Marie Antoinette likely had lovers during her reign (most notably, the Swedish count Axel von Fersen, with whom she exchanged love letters written in an elaborate code), the perversion attributed to her by her detractors was simply more fuel for the fire of hatred intended to weaken the regime. The character assassination was effective; upon her death at the guillotine on October 16, 1793, rabid crowds dipped their handkerchiefs in the queen’s blood and cheered when her disembodied head was raised up for view. The power of the press was rarely used for such ignominious ends.