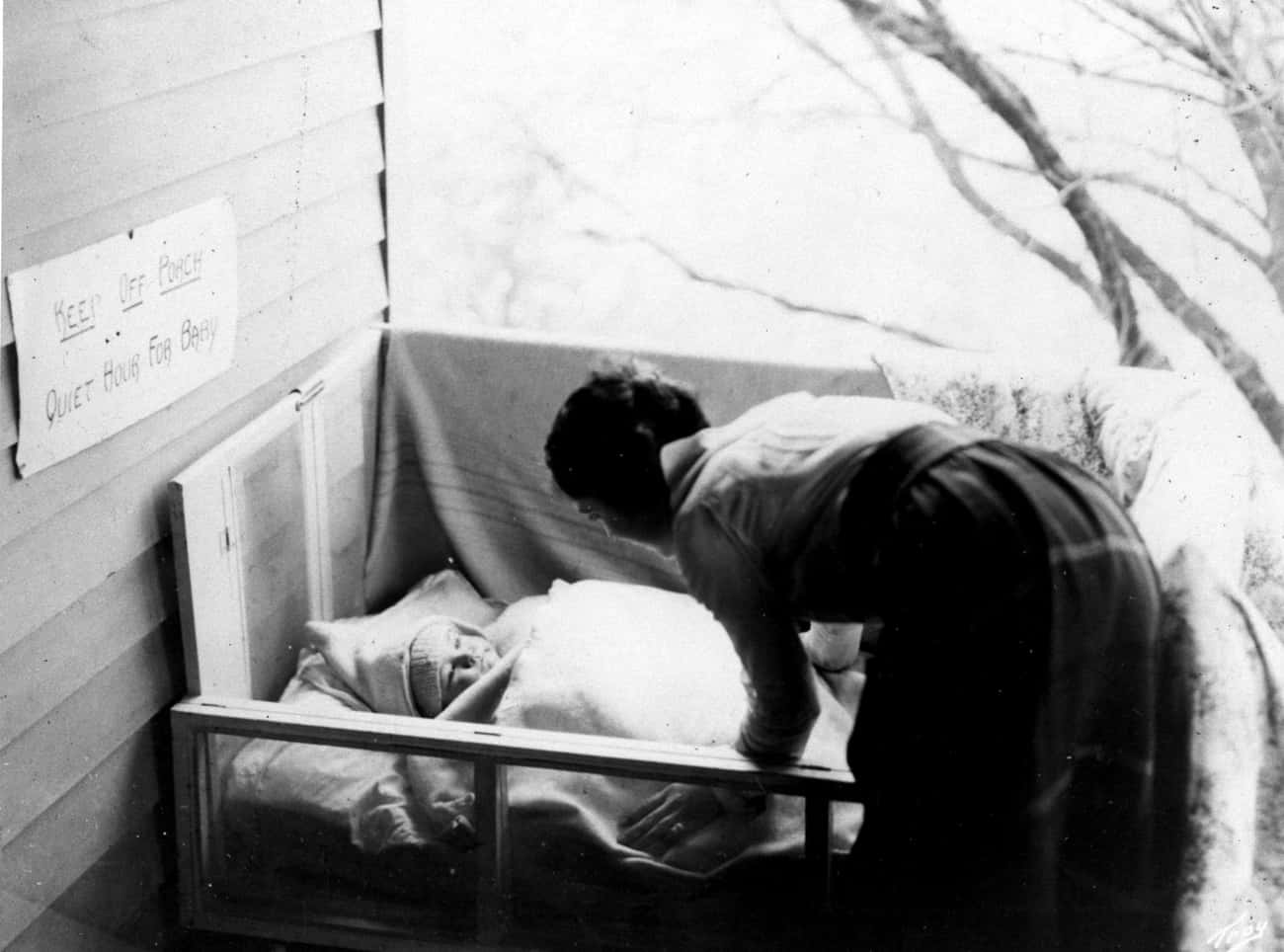

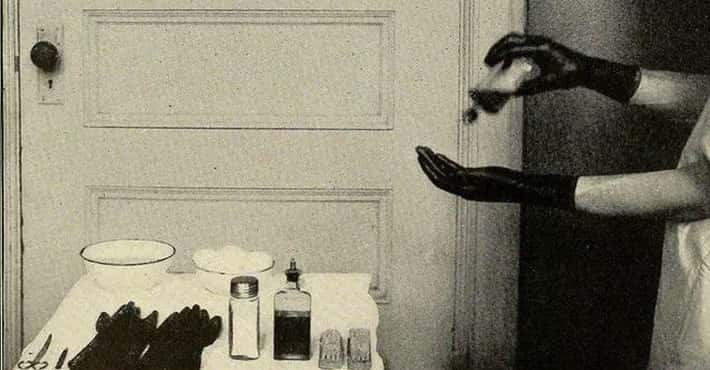

The Dystopian Program Of "Practice Babies" Where Orphan Infants Were Used To Train Expectant Mothers

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

Orphaned Babies Were Contracted Out To Local Universities

Universities like Cornell and Eastern Illinois State Teachers' College ventured out to local orphanages to find babies to use for practice. They entered into formal agreements with the institutions, basically leasing children for a time or until one side was unhappy with the arrangement.

There were a few instances where young children were willingly given over to a university by an unwed mother ill-prepared to take care of her child but not willing to give him or her up completely. One child in at the University of Nebraska was handed over for 30 weeks. The class that took care of her knew "that her people are very poor, practically destitute. The care of baby Kathryn Marie will receive in the training school will probably be far better than that which she could be given at home during the same time period."

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

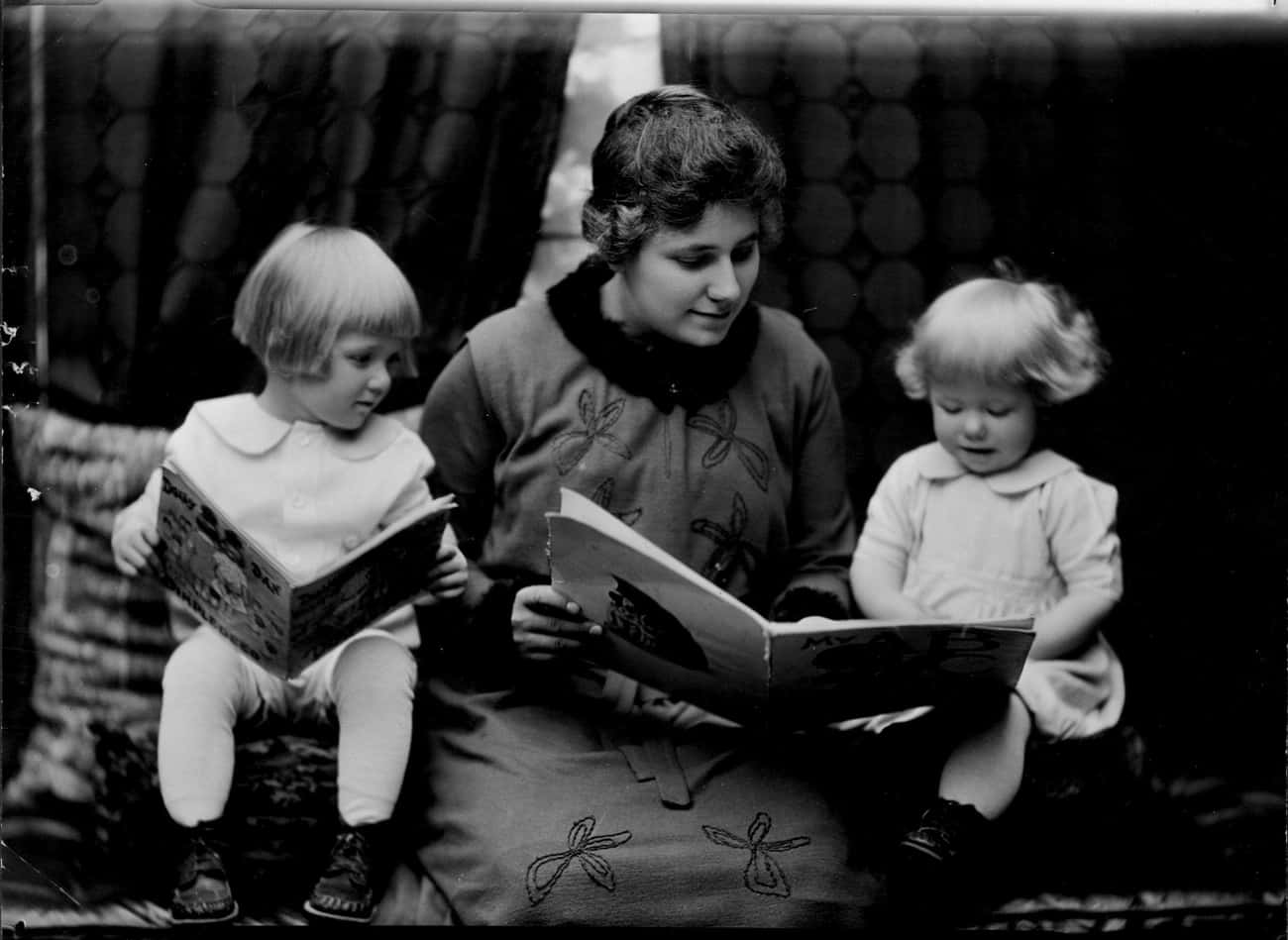

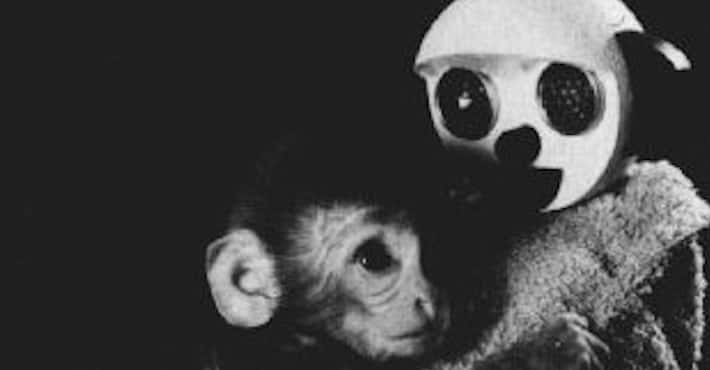

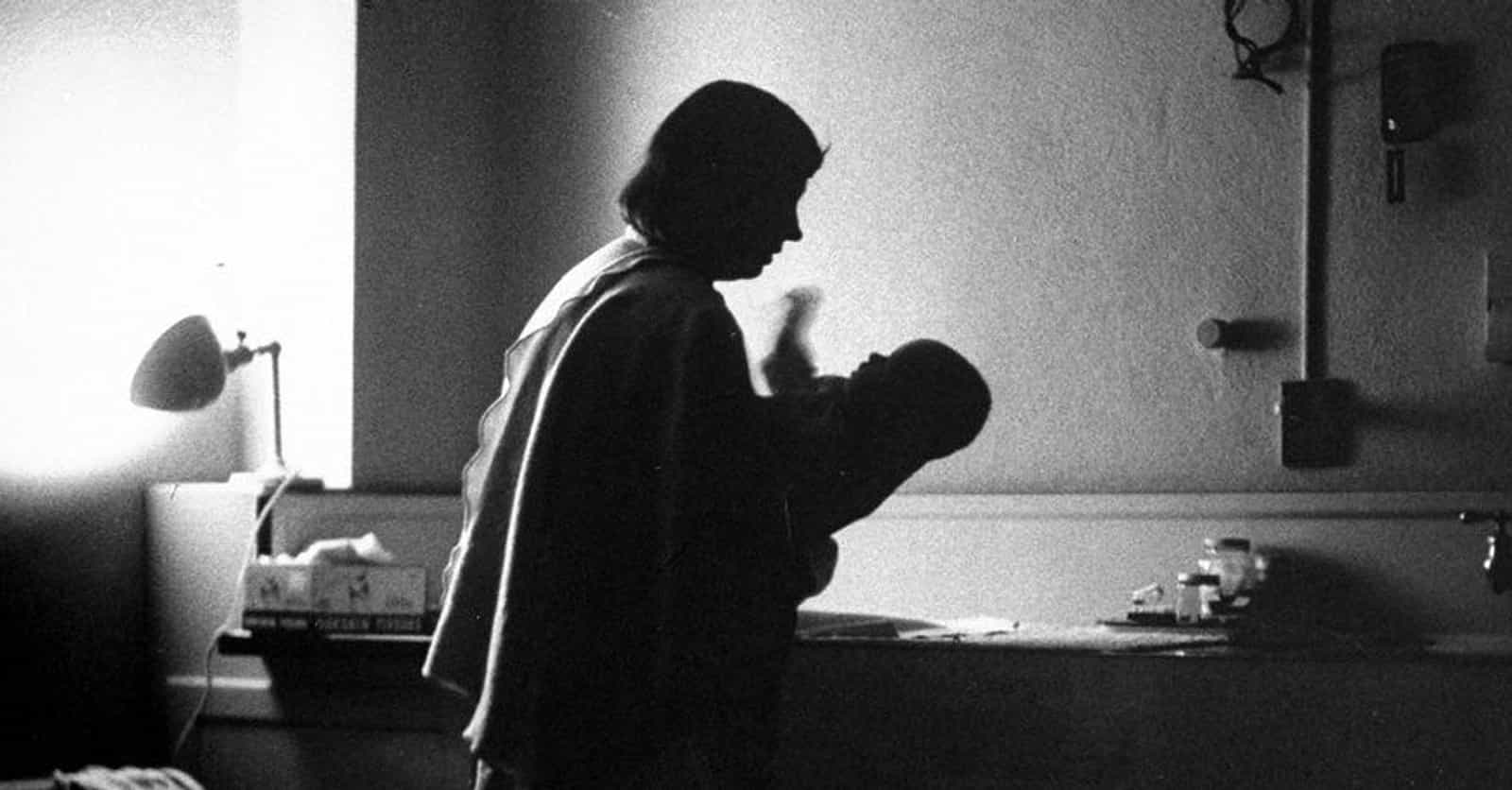

The Program Had Good Intentions But Fostered Emotional Detachment

Little attention was paid to practice babies when they were first used, but as media attention grew, there was increased controversy. The intent of the programs was to train mothers and to help children in need, "at the orphanage, there were not enough hands, and in this program, there were too many."

In 1954, the Child Welfare Department in Illinois looked at the program at Eastern Illinois State College and cried foul, calling it "not a normal setting." Other critics like Mrs. Babette Penner, director of the Women’s Services Division of United Charities, cautioned about the "anxieties there are in a child who is given a bottle in 12 or more pairs of arms." Former practice babies like Shirley Kirkman echo this, claiming she has spent her life unable to love and "dead inside" from the lack of forming strong relationships during the first years of her life.

Because no records were maintained on the infants that would allow for follow-up research, it's impossible to know how many of the children may suffer from these issues. However, psychiatrists warn "if a child doesn't form one really tight bond in the first years of life, it sometimes happens that he or she can develop attachment disorder."

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

Domecon Babies Were Highly Desirable When It Came To Adoption

There is evidence babies who received special attention in a home economics program were in demand when it came to adoptions. In 1929, Rebecca Murphy, a practice baby at the University of Maine, was sought out by 35 applicants. The babies had been well taken care of and were in good health (both desirable characteristics), and "prospective adoptive parents in this era desired Domecon babies because they had been raised according to the most up-to-date scientific principles."

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

Babies Were Given Last Names Derived From Their Practice Status

In the interest of anonymity, the children were given the surname that indicated their position as a practice baby. At Cornell University, the children were named Domecon - for domestic economics - and at Eastern Illinois State College, they were given a last name of North or South, indicating the building at which they were raised. At the University of Nebraska and others, the last names of babies were simply kept from the student mothers and they went by first names only.

The Babies Would Be Cared For By Numerous Women A Day

Although it varied depending upon the program, practice babies could be cared for by as few as eight and as many as 30 "mothers" at a time. In rare instances, one mother could have a baby for several days, but it was just as likely one woman would put the baby down for a nap and another would be there when the infant awoke. The length of time a baby would be in the care of the home economics class varied as well. It could last 30 weeks or one to two years.

- Photo: Cornell University Library / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The Babies Were Fed A Strict, Scientifically Engineered Diet

Many of the babies that entered the practice baby program were mal- or undernourished, and the food they were given by the student mothers benefited them greatly. The regimented and scientific diet emphasized nutritious foods and scheduled feedings. Children like Bobby Domecon were essentially saved by the program, arriving in a sickly state but thriving during the two years he spent as a practice baby.

- Photo: Cornell University Library / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

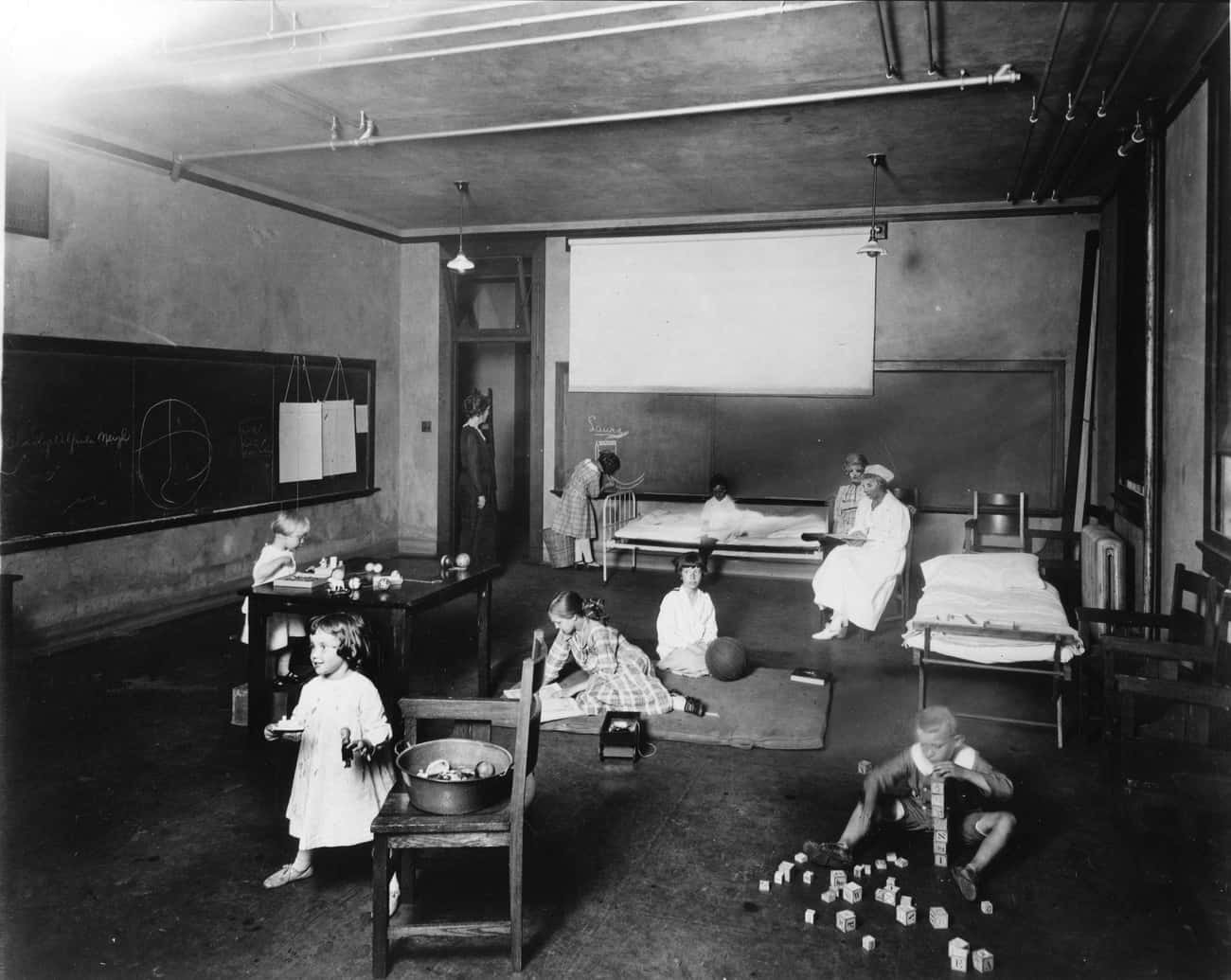

If A Baby Became Ill, The Student Mothers Lost Points

Just like the regimen for the baby was strict, the student mothers were also held to incredibly high standards. If a baby developed a cold, the mother got a demerit. If he or she got colic, more demerits. At the University of Nebraska - where students took care of the infant for one week at a time - it was only acceptable for the mother pro tem to touch the baby, but even then, "fondling" was to be kept to a minimum. The constant change-up and relearning of basic skills also meant that babies like Kathryn Marie were the recipient of novice care on a weekly basis.

The Babies Were Used In Practice Houses And Apartments

To create the mothercraft and domestic experience, home economics classes had entire houses and apartments to maintain. The practice babies were kept at the houses or apartments and cared for on a regular schedule by numerous women. The locations themselves created "a strange, artificial world." The apartment was stripped of anything that could be deemed cozy or comforting.

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

Domecon Babies Have Very Little Information About Their Time In The Program

Practice babies went back to their orphanage - or their mothers, less frequently - but were rarely aware of the time they spent in a home economics course as they grew up. The student mothers kept scrapbooks and baby books for each child but many didn't even know they had been part of a practice baby project. Donny Aldinger, for example, learned about his time at the Cedar Crest College program after investigating his past. He learned he had been a "boarder baby" taken from a local hospital and raised at the College for 13 months.

Another man learned from his aunt on her deathbed he had been a practice baby at Cornell and contacted the University as he searched for his birth parents, but they were unable to help him.

- Photo: Cornell University Library / flickr / Public Domain

Student Mothers And Practice Babies Are Looking For Answers

The use of pseudonyms combined with confidential adoption records and a lack of follow-up research on the children has made it difficult for the babies and student mothers alike to find much information about their temporary, experimental domestic lives. Former students like Ann Payan, Earlene Petty and Vicki Waller have searched for Baby David, who they cared for at Eastern Illinois State College, while former practice babies like Shirley Kirkman struggle to find answers about their backgrounds. Kirkman, who was a practice baby in Oregon, has no ill-will toward the program itself but also has no medical records or information about the time she spent there.