A single Beyoncé Instagram—just one (1) plain photo-and-caption post from the pop star—is worth around $1 million.

That’s per D’Marie, an analytics company that tracks social media reach. After measuring the influence of Beyoncé and other celebrities using 56 metrics including follower count, click-through rate, and general engagement, the company concluded that she is the highest-value influencer on social media, with her focus on “authentic, non-branded content” offering particular resonance and value.

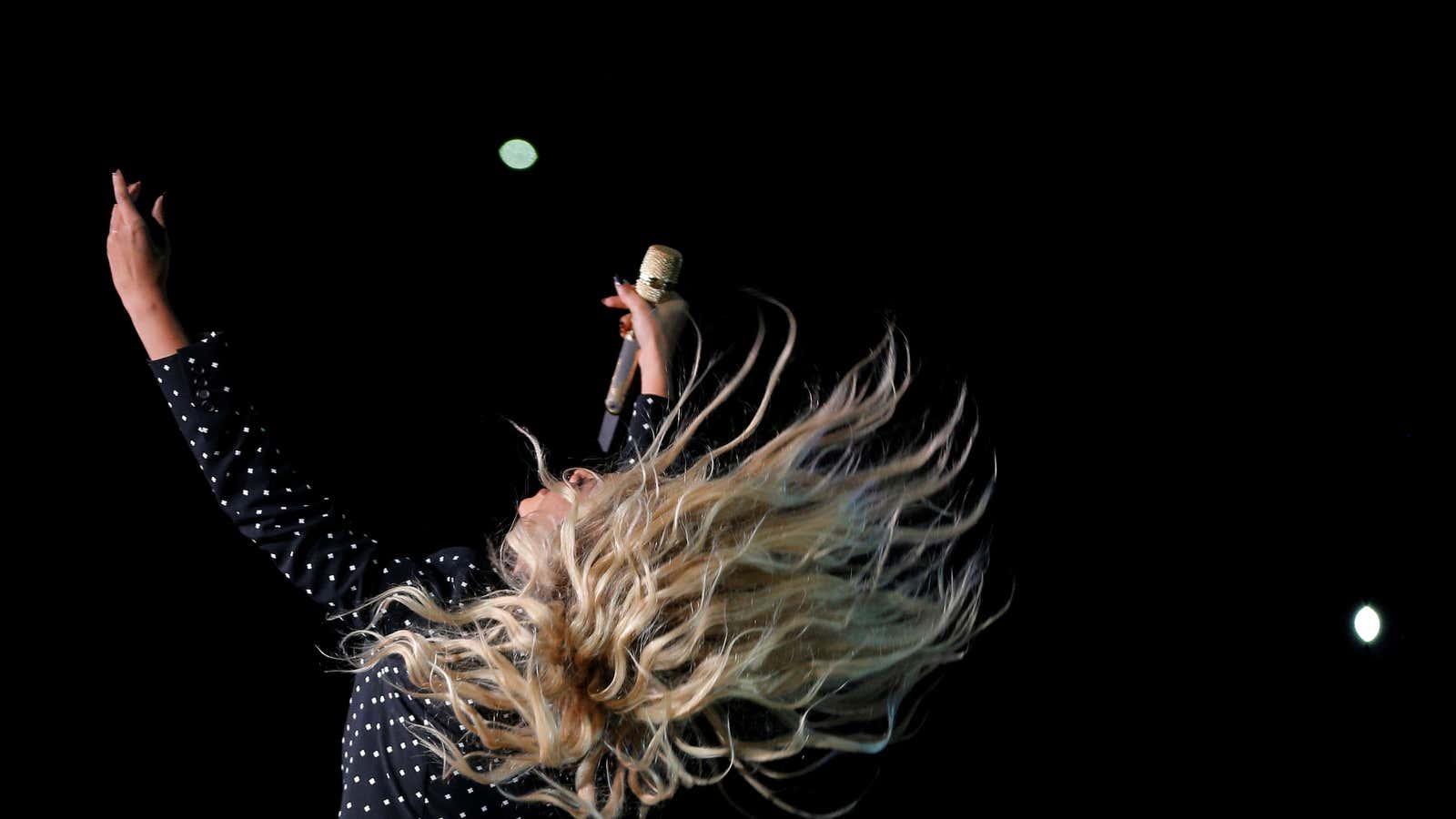

It’s certainly not all (if at all) Beyoncé’s doing. Stars of her size usually have entire teams of branding and marketing experts at the ready. But we want to believe. And she makes it so easy. When the singer announced her pregnancy earlier this year, she did so not to reporters or talk show hosts but on her Instagram; the post—which drew 7 million likes in 24 hours and is now the most-liked photo in the platform’s history—gives the impression, however manufactured, that Beyoncé wanted to take the personal news straight to her most devoted fans. To give back.

In under a decade, social media has become a powerhouse writ large for stars to bulk up their brand. Highly visual, interactive platforms like Instagram are exceptional at fooling us into thinking billionaire musicians are our friends, only a finger’s tap away, instead of towering on a stage or smiling, pixelated, on a big screen.

And this is where the money is, too. Thanks to rapid-fire developments in the industry—namely, the overnight rise of digital music, as well as digital everything else—the status quo has shifted. Record labels used to dictate everything from an artist’s entire album production process to his or her public relationships and personal appearance. Labels still preside over that first thing. But it matters much less.

“Album sales are not really a factor in financial planning conversations [with artists],” Sara Qazi, a financial advisor and director at Morgan Stanley Global Sports and Entertainment, tells Quartz. Since streaming services like Spotify pay out very little to artists and publishers, compared to the older formats of physical CDs and iTunes downloads, the money is no longer in albums. Says Qazi, “It has been a hard, hard shift in the economic model of the business. We have to look at where a musician’s business really is—and it’s mainly the live side, merchandise, or sponsorships.”

In other words, details that artists can control themselves, not requiring the backing of a label.

Beyoncé, social media extraordinaire, is a control freak in all aspects of her career. That’s how she, not to mention her sister Solange got where she is. Musicians these days are finally becoming their own merchants, as Beyoncé’s husband Jay Z prophetically rapped in 2014 (“I’m not a businessman; I’m a business, man! Let me handle my business, damn”).

Even back in record labels’ production territory, artists are usurping the balance of power. Logic, a rapper, set up a pop-up store and broke a sales record at his label. R&B singer Frank Ocean spent seven years in a “chess game” with his label, painstakingly buying back ownership all his music. Television also now premieres the best new indie music. Basketball star LeBron James is launching rap careers. Grammy-winning Chance the Rapper isn’t even signed and gives his music away for free.

As record labels slip out of import, tech companies—seeing a massive opportunity, and piggybacking on the sudden need for direct control—are also slipping in.

Instagram recently launched an entire music division, dedicated to helping artists promote themselves with exclusive content and audience metrics. Spotify, the leader of the music-streaming services, this year upgraded its Spotify for Artists program with nitty-gritty features such as the ability to add and control which playlists appear on a musician’s profile page, whether created by fans or other artists. A litany of startups have popped up to help artists message, market, or otherwise communicate with their fanbases. Gone are the days of music mogul Lyor Cohen’s famed 360 deal, a package that allows record labels to take a cut of all an artist’s revenues, including merchandise and concerts. (Cohen himself, fittingly, has jumped ship from the record industry to steer the music future of YouTube.)

Deezer, a Paris-based streaming service, is taking things a step further. Its new program Deezer Next selects a handful of small, promising artists and essentially aims to launch their careers. As Jorge Rincon, Deezer’s North America vice president, explains to Quartz:

Deezer Next for the industry is brand-new. It’s artist-first. We’ll do content curation, editorial, even artist promotion as part of our own advertising campaign, and invest our budget to feature DN artists for exposure to users. The branding of the artist will be exponentially increased.

Apple Music has mimicked the effort, highlighting a new artist every month with a featured called Up Next.

This isn’t to say record labels are going extinct. Musicians still need larger entities standing behind them to fund, create, and distribute recorded music. Plenty of labels, such as the small British XL Recordings, which discovered Adele, also still do good work cultivating artists’ budding talents. Yet promoting musicians, personalizing them, making them accessible to people—that’s all the work of tech companies now, if not artist themselves.

Deezer, separate from its grassroots Next program, has debuted an entire channel and marketing effort dedicated to grime, a homegrown British music genre that is slowly but haltingly making its way overseas. The idea is to bring the genre to millions of people who would otherwise not be exposed to it; Deezer is doing the same thing for the niche genre of reggaeton—one of whose biggest artists is currently featured the on the smash summer hit “Despacito.”

If those efforts see success—entire genres, their artists and all, lifted up by streaming services—then record labels might have genuine reason to begin to panic.