On Agnonizing in English

It is hard to convey the specific gravity of S. Y. Agnon in Israeli literary culture. For the Hebrew reader, Agnon is not merely canonical, he stands almost outside of time. One can get a sense of this in the recent remarks of one of Israel’s leading literary critics. Writing in Ha’aretz on the 50th anniversary of Agnon’s Nobel Prize in Literature, Ariel Hirschfeld described Agnon as unequivocally “the greatest Hebrew author of all generations.”

His place is amongst the greatest Hebrew writers of all times: the authors of the Torah and the book of Samuel; the poets of Psalms and of Song of Songs; the sages of the Mishnah and the great names of Hebrew poetry: Shlomo ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi and H. N. Bialik. Those who will compare his work to that of the great names of world literature will see clearly that there too his place is secure—side by side with the greatest of the great: Dante, Dickens, Goethe, Balzac, Flaubert, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Chekov, Kafka and Joyce.

One also gets a sense of Agnon’s unusual status in the words of Tel Aviv University literature professor Yahil Zaban in another recent Ha’aretz piece, bearing the bizarre and sensationalist title “Against Agnon. Or: This Is the Platform of Habayit Hayehudi Party.”

And as the platform of Habayit Hayehudi conceals within it religious oppression, patriarchal values, cynical neo-liberalism and a willful blindness toward the other, Agnon’s work too excludes Arabs and Mizrahis [Jews of Middle Eastern descent]; divides women into monsters and saints, presenting them as essentially inferior; views the larger Israel ideal as a God-given right and promise.

Needless to say, such fulminations are no more interesting than over-the-top panegyrics. The Agnon under attack here is more the Israeli icon, the bookish be-yarmulke’d image on the 50-shekel bill, than the subtle, ironic 20th-century modernist. Nonetheless, Zaban goes on to make an interesting point: Not only is there an unprecedented consensus around Agnon’s greatness, there is very little substantive criticism of him. In part this is, no doubt, because he did win the Nobel Prize, and in doing so seemed to validate the whole world of Hebrew literature, ridding it (for a while, at least) of its deeply ingrained fear of marginality and provinciality. It is also, perhaps, because Agnon is more respected than actually read in Israel, and this has been the case for a very long time.

Agnon’s literary project always bore a curious relationship to the Israeli national project. Nothing could be further from the mythical tzabar (the sabra, or native son of the Land of Israel) than Agnon’s old-world characters or the allusive quasi-rabbinic authorial voice in which he told their stories. Agnon himself was well aware of this tension. In the speech he gave upon receiving the Israel Prize in 1954 he described himself as “a stranger among my fellow [Hebrew] authors,” who was “condemned . . . for my lack of ‘Modernity’ and for my choice to write in the language of the books of the pious.” In fact, it was Agnon’s linguistic register, his choice of a literary style that somehow managed to feel continuous with the classics of premodern Hebrew, despite his deep, ironic modernism, that set him apart from the beginning. It seems to me that it was this stylistic choice more than anything else that has made him impossible both to ignore and to emulate; indeed impossible, or at least difficult, for contemporary Israelis to even read.

The Hebrew writer S. Yizhar was said to have hung a sign above his desk with the mock-biblical injunction “Thou Shalt Not Agnonize.” In A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz confesses to a similar struggle. It has been some time since this was a temptation for Israeli writers, who are mostly secular and, in any case, very far from Agnon’s world of rabbis, Hasidim, simple Eastern European Jews and “books of the pious.” Nonetheless, speaking personally, as an Israeli of Persian Jewish descent, I found Agnon’s work to be an enormous source of joy and inspiration from my first encounter with it. There is something about the grandeur of his language, the vividness of his imagery, the compressed power in his use of traditional symbols, and the intensity of the psychological drama in his work that captivated me immediately and irreversibly influenced my aspirations as a Hebrew writer. It was liberating to witness a writer use the Hebrew language so regally, making it sing like a well-tuned ancient lyre. Agnon’s religiosity, too, spoke to me as someone who had grown up in a traditional Jewish home, albeit one very far from Agnon’s Ashkenazi milieu. All of which is to say that, unlike many of my contemporaries, I have had to take S. Yizhar’s warning to heart and avoid writing in what others have called Agnonit (Agnonese).

Given all of this, there has always been something heroic, even quixotic, about rendering Agnon into English—and how much more so the late, difficult stories recovering the everyday history of his Galician hometown of Buczacz. These stories, which ranged from short fragments to a complex novella of local politics called “In Search of a Rabbi, or the Governor’s Whim,” were often published in Ha’aretz to little fanfare and some puzzlement. Even Agnon’s great friend and champion Gershom Scholem described this phase of the writer’s work as “peculiar” and perhaps more relevant to “students of folklore and Hebrew style than to readers of literature.” After Agnon died, his daughter Emuna Yaron published them together, in the sequence he had specified, in a massive book titled Ir u-melo’ah, and it is an ample, well-chosen selection of these stories that editors Alan Mintz and Jeffrey Saks have now brought together for the English reader in A City in Its Fullness. In doing so, they have succeeded brilliantly. As Mintz notes in his concise, judicious introduction, earlier Hebrew readers intimidated by the size and variety of the original collection had been put off from “exploring it in depth and discovering the full-fledged stories that are as brilliant as anything Agnon ever wrote.”

A City in Its Fullness is not the only work by Agnon that describes the Jewish life of his hometown. As a matter of fact, a large number of his works take place in Buczacz or a fictional surrogate. Much like Faulkner, perhaps the only American writer to whom Agnon might also be compared stylistically, who set most of his stories in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Agnon was trying to represent the spirit of his place and people with all their greatness and smallness. But there is something essentially different in A City in Its Fullness, something that separates it from the rest of Agnon’s body of work. Here he positions himself not as a subtly ironic—Scholem’s phrase was “dialectical”—modernist whose motivations were in the first place artistic, but as a humble, heartbroken preserver of memory.

In addition to eliminating many of the shorter pieces, Mintz and Saks took one quite brilliant liberty with what Mintz calls the “orchestrated sequence” that Agnon left his daughter. This was to begin, rather than end, the volume with Agnon’s story “The Sign.” As Mintz has written of this choice, it “makes the composition of the lament into an invitation to be emulated in the narrator’s belated prosaic mode of creativity.” In Arthur Green’s fine translation, the story begins:

In the year when the news reached us that all the Jews in my town have been killed, I was living in a certain section of Jerusalem, in a house I had built for myself . . . Myriads of thousands of Israel, none of whom the enemy was worthy even to touch, were killed and strangled and drowned and buried alive; among them my brothers and friends and family, who went through all kinds of great sufferings in their lives and in their deaths, by the wickedness of our blasphemers and our desecrators, a filthy people, blasphemers of God, whose wickedness had not been matched since man was placed upon the earth.

The unusually strong style and vocabulary of this opening seems to mark A City in Its Fullness not as a 20th-century work of short stories but as a medieval cycle of martyrdom stories, the heir to the long Jewish literature of destruction, which began with Lamentations. But the story (if that is what we should call it) takes an unexpected and indeed baffling turn. Immediately after Agnon laments the death of his family, friends, and neighbors, he writes:

I made no lament for my city and did not call for tears or for mourning . . . The day when we heard the news of the city was the afternoon before Shavuot, so I put aside my mourning for the dead because of the joy of the season when our Torah was given.

This surprising remark can and should be read on several levels. In the first place, Jewish law terminates mourning for the dead as soon as a holiday such as Shavuot commences, as Agnon expected his readers to know. But surely this is not all that is going on. Unable or unwilling to mourn for the world of his childhood and youth, Agnon does what he did best: reconstruct and resurrect it by his gift of storytelling. This decision is mediated by a strange occurrence that lends the story a mythological air. Late at night, as he keeps the traditional study vigil of Tikkun Leil Shavuot alone in the little neighborhood synagogue, the narrator is visited by the great medieval Hebrew poet Rabbi Shlomo ibn Gabirol, the author of the piyyut (liturgical poem) he is reading. This piyyut evokes the memory of the old hazzan (synagogue cantor) of his town, thus setting in motion the large mechanism of remembrance that is A City in Its Fullness. It is, Mintz writes, “a narrative of consecration.”

This story of visitation has echoes elsewhere in Agnon’s work, especially in the story “Le-fi ha-tza’ar ha-schar” (The Reward Is According to the Suffering) in which a righteous liturgist is the recipient of a poetic revelation he can never recapture. But it also clearly alludes to the famous legend about the composition of the U’netaneh Tokef, one of the great anthems of Jewish liturgy. According to this legend it was first uttered by Rabbi Amnon of Mainz as he was dying a martyr’s death on Yom Kippur. Three days later Rabbi Amnon revealed himself to the great liturgist Rabbi Kalonymus ben Meshullam (who died in 1096) and dictated the lyrics to him in a dream. In using this famous model Agnon appears to transform the festive holiday of Shavuot, “when our Torah was given,” into the somber Day of Atonement—a time of reflection and spiritual awe.

Agnon’s choice of Rabbi Shlomo ibn Gabirol as the vehicle of inspiration and remembrance is somewhat surprising. One might have expected him to choose a figure from the world which had been destroyed, not a great medieval Spanish poet. Agnon was, after all, a master of the whole Ashkenazi literary tradition. Then again, the seeming arbitrariness of the choice may betray the possibility of a strong autobiographical element in this story. In his excellent new monograph on this phase of Agnon’s career, Ancestral Tales: Reading the Buczacz Stories of S.Y. Agnon, Alan Mintz elaborates on this possibility:

The story presents the revelation of Ibn Gabirol as a profound event that actually took place rather than a dream or a reverie or a literary conceit. . . . As modern readers, we are well practiced in naturalizing the supernatural events we encounter in poems and novels by recourse to the fact that they are manifestations of the literary imagination. But the events in “The Sign” make a truth claim of a different sort. Agnon is saying to us, “with all due regard to literary imagination, this really happened.”

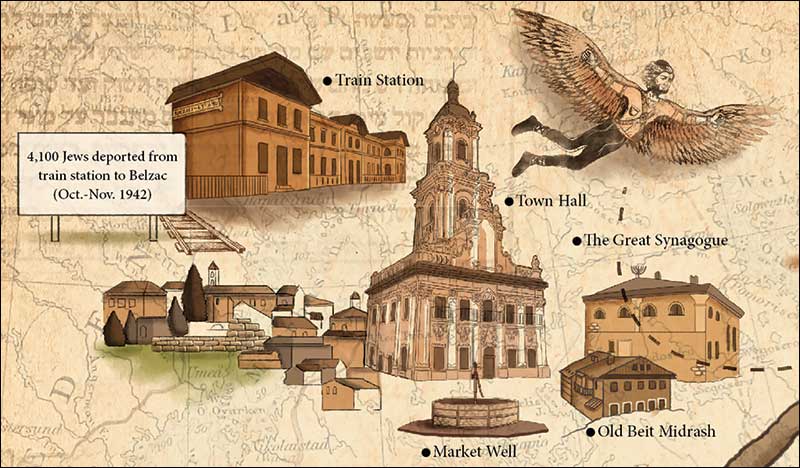

The stories of A City in Its Fullness are strung together as stations in a foot-journey around the now ruined town, each one of them a stop in this long stroll, and the editors have commissioned a map of Buczacz, beautifully designed by Elad Lifshitz, which graces the inside front and back covers, depicting life in the town in the shadow of death. But the journey is not only spatial, but also a journey in time—as it traces Jewish life in Buczacz from its mystery-shrouded mythological inception to the day of its brutal annihilation.

In his foreword to the stories—and with exemplary scholarly thoroughness in his monograph—Mintz draws attention to the values attached to each one of the stations on Agnon’s journey, such as charity, piety, studiousness, and devotion to prayer and ritual, but he is careful to recognize that Agnon was far from a simple didactic writer. “To be sure,” Mintz writes, “Torah study and worship are transcendental values that provide the key to the iconography of A City in Its Fullness. Yet the vivid liveliness of the stories depends on Agnon’s grounding these values in the concreteness of geography and history.”

Nonetheless, as Mintz knew, Agnon’s strength was not in the depiction of values and history, but in characters and situations. Agnon is a masterful drawer of characters and is especially potent when depicting characters and situations that are idiosyncratic, willful, or perverse. Agnon resurrects his hometown and its colorful characters in all their complexity, never once succumbing to the temptation to flatten them into two-dimensional martyrdom. This refusal to bask in nostalgia and sentimentalism is, in my opinion, his true rebellion against the horror. Nor did he forget when his beloved community betrayed its values. In the story “Disappeared,” the narrator takes a jab at the community’s self-image as a compassionate people: “So what did that woman live on? What sustained her? If not her suffering, then it was only her saliva that kept her alive, as she had told R. Leibush the parnas before he took her son from her.” The great diversity of themes and modes of narration in these stories may be the result of the fact that they were written over many years, but it might also be seen as part of the book’s statement, as Agnon’s goal was to resurrect all aspects of the past, not just those which seem “worthy” of lament.

As it turns out, loss hovers over the production of A City in Its Fullness. As originally conceived, the translation was to have been undertaken by James S. Diamond. At the end of his foreword, Mintz reports:

Sadly, in April 2013 he was killed by a car while standing near the home of a friend in Princeton, New Jersey. He had prepared draft translations of several of the stories, and those have been completed and edited by Jeffrey Saks. Other translators were invited to step in to complete the task. A City in Its Fullness is dedicated to Jim’s memory.

As I was writing this review, I received the startling news that Alan Mintz himself had suddenly passed away. These two new books will now stand not only as a testament to the genius of S. Y. Agnon but as a memorial to Alan Mintz, who was a lifelong scholar and, more importantly, an avid lover of Hebrew literature.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Light Reading

Stoicism and the human heart.

Brotherhood

How did the world's most antisemitic play become a symbol of positive Christian-Jewish relations? Karma Ben Johanan's new book explores an evolving dynamic.

Screwball Tragedy

Picture a Jewish town, located deep in a Polish forest, that hasn’t received so much as a postcard from the outside world in more than a century. Max Gross conjured it up The Lost Shtetl: A Novel, and the result is both screwball and serious.

Another Round with Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer had the gift of enlivening everything he touched. And he touched almost everything, from politics to Hollywood to Sports. But his Jewish novel stayed in the drawer.

Marcus moseley

Thanks for this perceptive article!

"Parallel Lives" of Agnon/Isaac Bashevis Singer may shed light on each and both.

Each was mesmerized by Mirrors.

MM