2017 marks the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. As such, we are joining in the celebration with a series of articles throughout the year that will address the Reformation from the perspective of cross-cultural missions.

2017 marks the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. As such, we are joining in the celebration with a series of articles throughout the year that will address the Reformation from the perspective of cross-cultural missions.

If you were living five hundred years ago and wanted to read the Bible, where would you turn? Back then, even in Europe, you would have struggled to find Scripture in anything other than Latin, a language known only to the scholarly elite.

What about one thousand years earlier still? By the fourth century, portions of the Greek and Hebrew Bible had been translated into numerous Coptic dialects in Egypt and into Ethiopic a century or so later. The Bible was also available to speakers of Syriac, a sister language to Hebrew and Aramaic [1]. Other African Christians who lived during that crucial era had to make do without Scripture in their mother tongue, a fatal disadvantage when Islam came to North Africa in the seventh century. Over the next two hundred years the church effectively disappeared across the region in all but three key areas: the very same areas where Coptic, Ethiopic, and Syriac were spoken. Wherever followers of Jesus could read the Bible in their own language, they stood firm [2].

The First Bible Translation in English

It was this reality that drove John Wycliffe to translate the Bible into English in the fourteenth century. After all, the Czech wife of England’s Richard II had Scripture in her heart language, but the king did not. The work was completed in the late 1380s. When challenged in court, Wycliffe responded:

“You say it is heresy to speak of the holy Scriptures in English. You call me a heretic because I have translated the Bible into the common tongue of the people. Do you know whom you blaspheme? Did not the Holy Ghost give the Word of God at first in the mother-tongue of the nations to whom it was addressed?” [3]

Each copy of Wycliffe’s translation was produced by hand, which cost the equivalent of a vicar’s annual salary. So it was never widely available any more than other translations elsewhere in Europe.

“You say it is heresy to speak of the holy Scriptures in English. You call me a heretic because I have translated the Bible into the common tongue of the people.”

—John Wycliffe

Luther, Tyndale, the Printing Press, and an Explosion of Scripture Translation

This was all to change with the Reformation, which greatly benefited from the recent invention of the printing press, an innovation that changed the nature of books forever. Luther led the way, issuing a translation of the New Testament in German in 1522. This was a roaring success, going through forty-three editions in just three years with a total printing of over 100,000 copies [4].

The first Dutch vernacular Bible was next, followed by William Tyndale’s English New Testament in 1526 and a complete French Bible in 1530. Tyndale’s motivation for these Bible translation projects was one of the central aims of the Reformation—to get the Bible into the hands of lay people so they could read it themselves. He observed [5]:

“I had perceived by experience, how that it was impossible to establish the lay people in any truth, except the Scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother tongue, that they might see the process, order, and meaning of the text.”

Tyndale was executed not long after. His last words were “Oh Lord, open the King of England’s eyes” [6], a prayer wonderfully answered when just three years later King Henry VIII finally allowed, and even funded, the printing of an English Bible known as the “Great Bible.”

A string of English language translations followed: the Coverdale Bible, the Great Bible and, in 1611, the King James Bible: the most printed book in the history of the world. By 1600, European language translations also existed in Italian, Catalan, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Polish, Slavonic, Slovenian, Welsh, and Hungarian, with Finnish, Irish, Latvian, Lithuanian, Romanian, and Romansch added in the following century.

“Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most holy place; that removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water, even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered” (Translators’ Preface, King James Version).

What about languages further afield? In 1663, John Eliot printed the first Bible in America. It was in Algonquin, the language of Native Americans in Natick, Massachusetts. On the other side of the world, Albert Ruyl, an agent of the Dutch East India Company, was the first to translate Scripture into a modern Asian language, Malay. His translation of the New Testament was completed in 1688, and another in Tamil followed in 1715.

The Golden Age of Bible Translation and the Modern Missionary Movement

But the floodgates of Bible translation really opened with the modern missionary movement. Henry Martyn translated the New Testament into Urdu, Persian and Judeo-Persian before his early death at the age of thirty-one. Meanwhile, in India, William Carey and his associates were involved in the publication and translation of Scripture in forty languages.

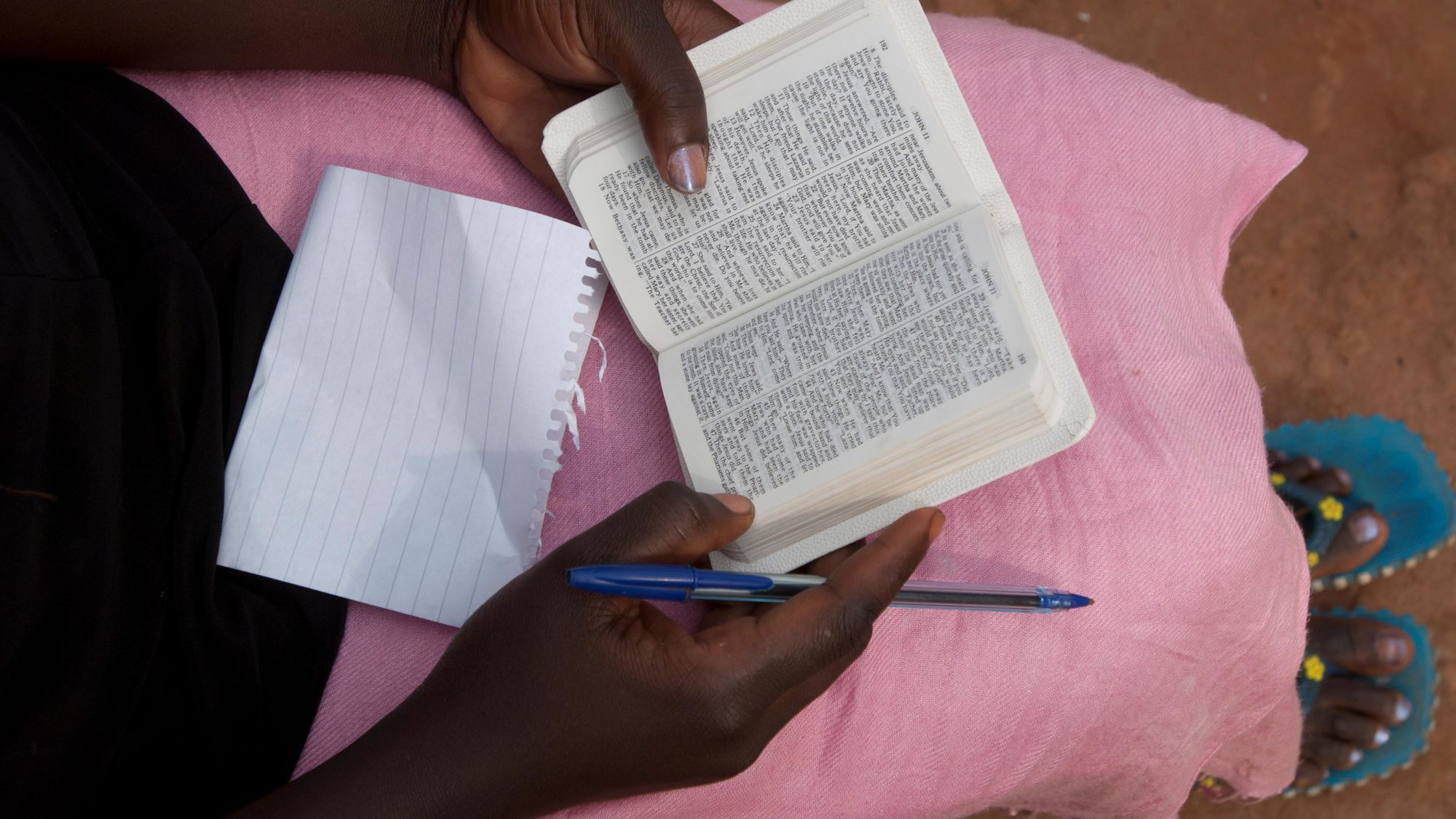

Consider the challenge facing our generation: more than 1.5 billion people still do not have the full Bible available in their first language.

In 1884 Samuel Crowther, the first African Bishop of the Church of England, completed his translation of the whole Bible into Yoruba. And Pandita Ramabai was one of a long line of women pioneer translators. She learned Hebrew and Greek in order to produce a version of the Bible in a colloquial version of the Indian Marathi language, which could be understood by people at every level of society.

This idea of being understood by all had been crucial to Luther’s pastoral heart back at the beginning of the Reformation. He wrote: “. . . we must inquire about this of the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the marketplace. We must be guided by their language, the way they speak, and do our translating accordingly. That way they will understand it. . . .” [7]

Into the Twenty-First Century: Will There Ever be a Bible in Every Language?

By 1965, the Roman Catholic Church was officially giving its blessing for Bible translation into vernacular languages, announcing that easy access to sacred Scripture should be provided for all the Christian faithful. [8] By the end of the twentieth century—thanks not least to Reformers like Tyndale and Luther—portions of Scripture had been translated into more than three thousand languages all over the world. And God continues to open the door for Bible translation and distribution in the most surprising places. Still, the work is far from done. Just consider the challenge facing our generation: more than 1.5 billion people still do not have the full Bible available in their first language.

One Reformation theme with an interesting modern parallel is that of mobile phones. Mobile technology may prove as significant for the distribution of Scripture today as the printing press did for the Reformers. Tyndale was hounded to his death and his Bible burned wherever it could be found. What would he make of a device capable of downloading the Bible in hundreds of languages in a matter of seconds, free of charge? What would he think of a handheld device that can read the text out loud, accompanied by pictures or videos? May Scripture be plainly laid before the eyes of the world in their mother tongue!

Michael Gabriel serves with SIL International as a linguistics and translation consultant for a number of communities in Central Asia. His passion is to see peoples across the region delight to know and worship Jesus in the unique and precious languages and cultures that God has given them.

If you’d like to be involved in getting the Bible into the hands of peoples who’ve not had the opportunity to read it in their own languages, check out these IMB projects:

Scripture Planting in East Asia

StoryOne Sign Language Scripture Translation

God’s Truth for Bible-less Peoples

You can also use our Project Finder tool to search for others.

NOTES

[1] Bruce M Metzger, “Important Early Translations of the Bible,” Bibliotheca Sacra 150: 35-49, 1993.

[2]Of course other factors were also at play, including the degree of indigenous leadership, and church-state relations. See Calvin E. Shenk, “The Demise of the Church in North Africa and Nubia and Its Survival in Egypt and Ethiopia: A Question of Contextualization?” Missiology: An International Review, Vol. XXI, No.2. 1993.

[3]Quoted in David Fountain, John Wycliffe: The Dawn of the Reformation. Revival Literature, 1984.

[4]For the details, see chapter 7 of Andrew Pettegree (ed), Reformation World. Routledge: London, 2000.

[5]Tyndale’s preface to the Pentateuch, 1530.

[6]Recorded in Foxe’s (1563) Book of Martyrs.

[7]LW 35:188-189 Fuller citation: An Open Letter on Translating By Dr. Martin Luther. Translated from: “Sendbrief von Dolmetschen” in Dr. Martin Luthers Werke, (Weimar: Hermann Boehlaus Nachfolger, 1909), Band 30, Teil II, pp. 632-646 by Gary Mann, Ph.D.

[8]The relevant paragraph (22) reads: “… since the word of God should be accessible at all times, the Church by her authority and with maternal concern sees to it that suitable and correct translations are made into different languages, especially from the original texts of the sacred books. And should the opportunity arise and the Church authorities approve, if these translations are produced in cooperation with the separated brethren as well, all Christians will be able to use them.” Dogmatic Constitution On Divine Revelation Dei Verbum Solemnly Promulgated By His Holiness Pope Paul VI On November 18, 1965.