The Last Days of the Other 1 Percent

Next week’s deadline to qualify for the third Democratic debate could leave half of the large field of candidates on the sidelines.

For a handful of Democratic candidates stuck at 1 percent (or lower) in the polls, a Wednesday afternoon in the dog days of August could be the moment when their lifelong dream of the presidency dies a quiet death.

August 28 is the deadline for candidates to meet the Democratic National Committee’s heightened threshold for entry into the September debate, and as much as half the field is expected to wind up on the sidelines. Those who don’t make the cut will, at a minimum, be forced to reassess the viability of their long-shot bids. Some of those also-rans may trudge on through the fall, in the hopes of rebounding for the next debate in October, or simply out of a commitment to stay in the race until the first votes are cast in Iowa next February.

But for all intents and purposes, next Wednesday will mark the first great winnowing of the 2020 White House race, when a field of more than 20 is cleaved into two divisions: those who still have a shot, and the rest who don’t.

Governor Jay Inslee of Washington, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, Representative Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, Representative Tim Ryan of Ohio, and the author Marianne Williamson are among the other hopefuls who could be on the outside looking in next month.

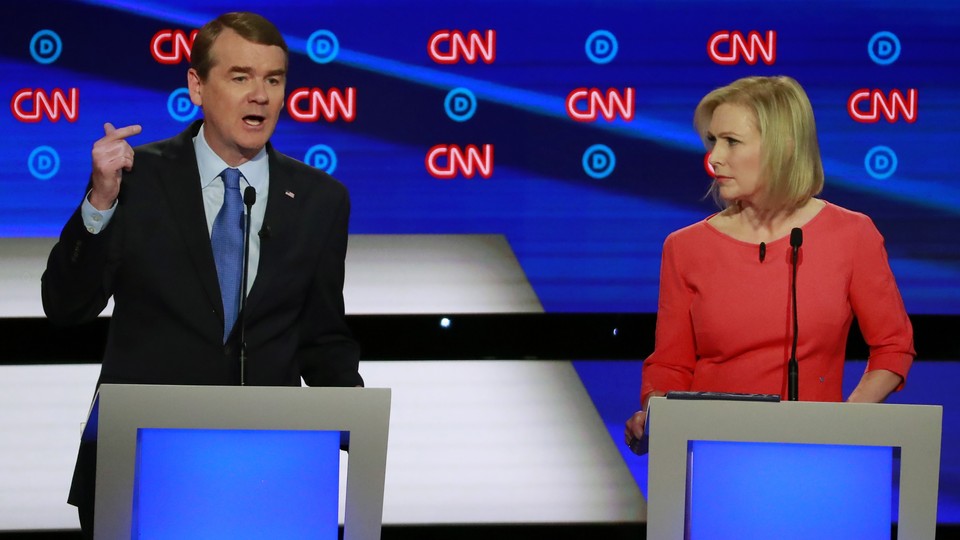

As of this morning, 10 of the roughly two dozen Democratic hopefuls have secured spots by receiving donations from at least 130,000 individual contributors and registering 2 percent support or higher in four qualifying polls. The billionaire Tom Steyer is close to the marker, and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York has bought more than $1 million in television ads in Iowa and New Hampshire as part of an aggressive late push to get her to 2 percent in the three additional polls she needs to qualify. (She said this week she has just over 110,000 donors, putting her within reach of that threshold.)

But with a week to go before the deadline, a handful of campaigns have all but conceded they aren’t going to make it, and some have directed their ire on the Democratic National Committee instead.

“The DNC leadership in Washington has taken unprecedented steps to intervene in a nomination process that should belong to Democratic voters and caucus-goers,” Craig Hughes, a senior adviser to Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, says. Bennet is among the candidates who participated in the first two debates and is likely to fall short of the threshold for the third. “By limiting participation in the debates through arbitrary rules developed in secret without consultation with state party chairs, activists, or actual DNC members, a few operatives in Washington went into a backroom to put a thumb on the scale on behalf of perceived frontrunners, celebrities, and billionaires who can buy their way in.”

Hughes says that the DNC’s effort to narrow the field this fall “could leave us weaker, not stronger, in the general election” as the party tries to defeat President Donald Trump. Lagging Democratic campaigns have been battering the party committee for months over its decision to add a donor requirement and to nearly double the threshold it created for the first two debates this summer. But those critiques are getting sharper as candidates confront the likelihood that their exclusion from the debate could leave them without any real shot at momentum ahead of the first contests in February.

Already two candidates who appeared in the initial debates have dropped out: Representative Eric Swalwell of California and Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, who announced last week he would consider a run for Senate instead. Representative Seth Moulton of Massachusetts and Mayor Wayne Messam of Miramar, Florida, have not made any of the debates but have continued their campaigns anyway.

And as The Atlantic’s Edward-Isaac Dovere reported last week, some of the long-shot candidates are particularly incensed that Steyer, the wealthy liberal activist and impeachment agitator, was able to so easily reach the donor threshold by pouring millions into ads and the purchase of voter files from his own outside organizations. By contrast, candidates without that access to personal wealth have had to devote their resources to Facebook and other online ads designed to raise small-dollar donations solely to gain entry to the debates.

“I think the DNC was in an unenviable position with this many candidates, and I think I know what they were trying to do,” Matt McKenna, a senior adviser to Montana Governor Steve Bullock, told The Atlantic. “But I think there’s just universal agreement that they failed.”

Bullock missed the first debate in June after entering the race in May. He made the stage last month in Miami, but he was unable to capitalize on the appearance, and his campaign sees a better chance of making the fourth debate in October than next month’s matchup. But unlike some candidates, he has not spent as much money simply trying to persuade people to contribute as little as $1 to reach the DNC’s donor threshold. “If I gave him $100, I wouldn’t want him to go spend $70 of it to go get one more dollar,” McKenna said. “If you say it aloud like that, that’s when you realize the absurdity of this situation that they’ve created.”

Michael Hopkins, a spokesman for former Representative John Delaney of Maryland, says the DNC had “learned nothing from 2016,” when it was criticized for purportedly favoring former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton over Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont in the primaries.“By requiring campaigns to hit this arbitrary donor goal it forces campaigns to talk about more divisive issues and not be on the ground and instead go on Facebook and Twitter,” Hopkins says.

DNC Chairman Tom Perez has defended both the concept of the donor threshold, which is designed to measure grassroots support, and the party’s decision to tighten the requirements for the fall debates. “We have been doing exactly what happens in every Democratic primary process,” Perez told The Atlantic earlier this month. “The closer you get to the first elections, we raise the bar gradually, fairly, and transparently.”

Defenders of the debate rules point out that the DNC is an easy scapegoat for candidates who have failed to gain traction despite months of campaigning and plenty of opportunities to break through, either in the initial debates or in the many prime-time town halls broadcast on the cable networks. And the committee received plenty of criticism for allowing the first debates to be as wide open as they were, with a record 20 candidates onstage over two nights.

None of the campaigns we spoke with said explicitly they would drop out if they were shut out of the fall debates. Indeed, a few staffers actually questioned the importance of the events themselves, pointing out that the debates in June and July did little to change the dynamic of the race. Senator Kamala Harris of California shot up in the polls after her performance against former Vice President Joe Biden in Miami, but she fell back after the next debate in Detroit. The same five candidates—Biden, Harris, Sanders, Senator Elizabeth Warren, and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg—occupy the top tier now as they did in the spring. The rest of the field is hovering in the low single digits at best.

“Not making one debate is not deadly to a campaign,” Hopkins says. “Should we not make it, we’ll go directly to Iowa and New Hampshire. We have a plan either way.”

A senior staffer to another long-shot candidate, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to give an unvarnished view, was even blunter: “I think it’s absolutely insane how much people are putting into these debates,” the aide said. “If you look at the polling, the debates didn’t do shit for polling.”

That is not the view of Gillibrand, who sees the fall debates as perhaps her last chance to jolt her campaign into contention after a lackluster start. While the last debate in Detroit provided no real bounce to any Democrat, Gillibrand’s campaign said it had its biggest fundraising day of the race afterward, and she hit 2 percent in one of the four polls she’ll need to qualify for the stage in Houston. The New York senator says she is closing in on 130,000 donors and timed her latest ad buy in Iowa and New Hampshire to reach 2 percent in three more polls. “The debates are clearly an important place to be and to have your voice heard,” the Gillibrand spokeswoman Meredith Kelly told The Atlantic. “It is a platform that matters quite a bit and drives the conversation.”

The bigger question for Gillibrand, and for many of her struggling rivals, is what they’ll do if they don’t qualify. On that, Kelly was noncommittal. “That’s not even a conversation we’re entertaining right now,” she said.

Christian Paz contributed to this report.