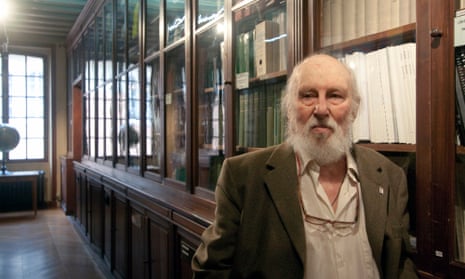

Sidney Holt, who has died aged 93, aimed to live long enough to save the great whale species from extinction – something he had been fighting for since being appointed to the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1961 to give scientific advice on annual catch limits for each hunted species.

He managed to curtail the slaughter but did not succeed in halting it until 26 December 2018, when Japan left the International Whaling Commission and announced it would no longer kill whales in Antarctica, at last guaranteeing the great whales a sanctuary where their seriously depleted numbers might continue to recover.

Holt’s battle to save the whales began after he had established himself as a world-renowned scientist in the field of fisheries, having co-written a book published in 1957 on how to calculate fish stocks and therefore work out sustainable catches. The book, On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations, was a collaboration with a fellow UK Ministry of Fisheries and Food (Maff) scientist, Ray JH Beverton. It became the must-have textbook for fisheries scientists.

Holt had worked out the equations that formed the core of the book while camping on Rannoch Moor in Scotland, waiting for wood ants to return to their nests. He had been sent out on a motorbike to scout for areas of Scotland that could be turned into nature reserves, and out of curiosity began weighing the ants when they set off to forage in the morning. He marked them with tiny spots of green paint so he could identify individuals when they returned and weigh them again.

He posted off the fishery equations to his co-author and four years later the ministry published the results, establishing the international reputations of both men.

Holt, who had an intense curiosity, believed in spreading his knowledge and had already represented the UK at various international conferences on fishing. Four years before the book was published he was asked by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to run a training course in Istanbul, after which he was recruited to work full time.

Holt and his wife, Nan (nee Meadmore), known as Judy, whom he married in 1947, went to live in Rome, and he spent the following 25 years working for the UN. His reputation continued to grow as he produced more than 400 scientific papers and articles. He served as director of the fisheries resources and operations division of the FAO in Rome, secretary of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and director of Unesco’s marine sciences division in Paris.

In 1961, as a part-time additional job, he became one of the so-called “three wise men” – independent scientists advising the IWC, which was intent on devising sustainable limits to catches of great whales. Although he officially retired from the UN in 1979, he continued work to limit the slaughter of whales, first for the IWC until 2002, and then as a scientific adviser to various anti-whaling countries, including the Seychelles and France, as well as environment groups.

After retiring from the UN he became first director of the International Ocean Institute in Malta and helped draft the Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982).

He won many accolades for his work on protecting marine mammals, animal welfare and fisheries science, including the Global 500 award of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Blue Planet award of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW).

Sidney was born in the East End of London. His father, also Sidney Holt, was a briar-pipe maker, and his mother, Ethel (nee Fryatt), had worked in a confectionery factory. They moved to Colindale and Sidney won a scholarship to Haberdashers’ Aske’s boys’ school before going to Reading University, where he got a first-class degree in biology. He wanted to continue studying but his parents could not afford to support him and he joined Maff, working in its Lowestoft laboratory.

Although he began his research life at sea, sewing buttons on plaice and releasing them to determine where they had migrated when they were caught again by fishermen, he was soon in demand elsewhere. He was keen to accept a job in the US at five times his Maff salary, but was refused a visa. He later discovered he had been labelled a communist for helping two visiting Russians translate their scientific paper into English.

Instead of America he worked at Nature Conservancy in Scotland before joining the UN in Rome.

Holt was proud to have worked for the UN, but it was saving the great whale species that became his passion. He used his scientific, communication and diplomatic skills to turn the IWC from pro-hunting to a conservation body, a process that took decades of dedication.

The first great milestone in saving the whales came when a moratorium was introduced in 1984. However, Japan immediately invented “scientific” whaling – killing whales to check their age and the state of the stock – a loophole that allowed it to continue to slaughter the mammals for meat, also exploited by Norway and Iceland.

The annual meetings of the IWC were a political battleground in which Holt was ever present, patiently explaining the science and revealing to journalists the “bribes” of fish plants and cash sums used by Japan to get small nations to vote alongside it.

As he got older he grew more radical and became a Greenpeace representative, helping to found Greenpeace Italy, advising the IFAW, and finally endorsing the work of the Sea Shepherd organisation, directly confronting the Japanese whaling fleet as it hunted in the designated Antarctic sanctuary.

When Japan announced it had stopped “scientific” whaling in the Antarctic the news was hardly reported, but last September, when Holt was physically ailing, a group of prominent whale campaigners from around the world made a pilgrimage to his home in Umbria to celebrate and thank him for his immense contribution to their cause.

He met his partner, Leslie Busby, while they were working at Unesco. She survives him, along with his son, George, from his marriage to Judy, from whom he separated in the late 1970s.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion