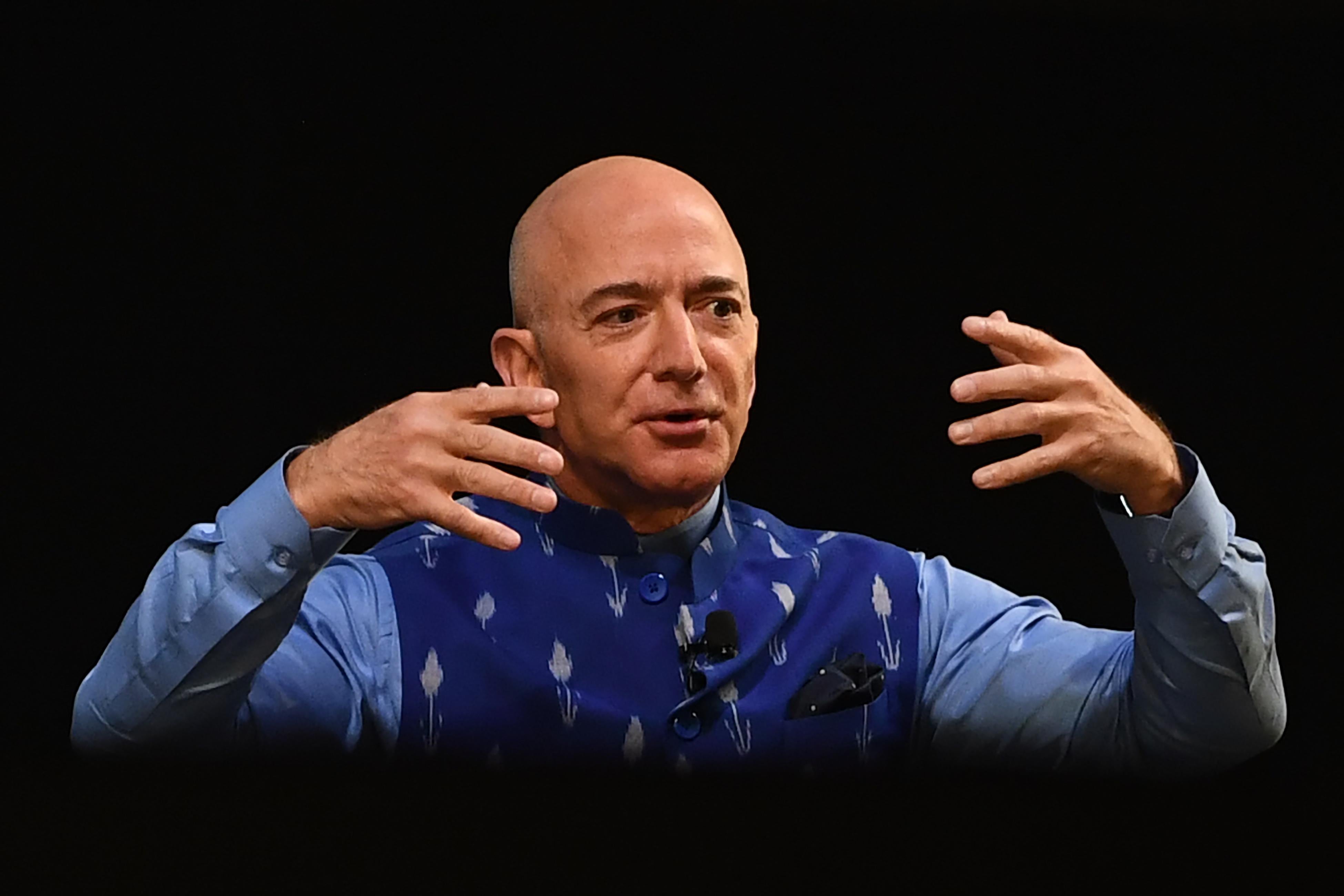

Nothing really makes sense about the story claiming that Jeff Bezos’ phone was hacked via malware sent in 2018 from the WhatsApp account of Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia. Why would Saudi Arabia infiltrate Bezos’ phone in such a brazen and obvious way, through a WhatsApp account linked to the nation’s crown prince? Why would it later leak Bezos’ personal photos and text messages to the National Enquirer? Why would the photo of a brunette woman sent to Bezos from MBS’ WhatsApp account with the caption “Arguing with a woman is like reading the Software License agreement. In the end you have to ignore everything and click I agree” be evidence that MBS knew of Bezos’ impending divorce?

Overall, the allegations assembled in a report prepared for Bezos by FTI Consulting raise as many new questions as they answer. Following the National Enquirer’s unsuccessful attempts to blackmail him last year, Bezos asked FTI to investigate his phone. FTI determined that on May 1, 2018, MBS sent Bezos a video file via WhatsApp and that it was “highly probable” that the file contained malware that enabled the subsequent theft of a large volume of Bezos’s data several hours later. However, FTI did not find any evidence of that malware on the phone.

Instead, to support its determination that Saudi Arabia was responsible for stealing and then passing material on to the National Enquirer, FTI relied on the timing of the video file’s delivery, which came just before the exfiltration of data from the phone, and a series of peculiar but not obviously incriminating messages from MBS to Bezos.

The phone was definitely breached. Both the distribution of his private photos and the digital forensic evidence from FTI’s analysis make clear that information was stolen from it in large volumes in the months following his receipt of the video from MBS. The report states:

The amount of data being transmitted out of Bezos’ phone changed dramatically after receiving the WhatsApp video file and never returned to baseline. Following execution of the downloader sent from [MBS’s] account, egress on the device immediately jumped by approximately 29,000 percent.

Forensic artifacts show that in the six (6) months prior to receiving the WhatsApp video, Bezos’ phone had an average of 430KB of egress per day, fairly typical of an iPhone. Within hours of the WhatsApp video, egress jumped to 126MB. The phone maintained an unusually high average of 101MB of egress data per day for months thereafter, including many massive and highly atypical spikes of egress data.

So someone was remotely stealing information from Bezos’s phone for an extended period of time. The challenge comes in linking that exfiltration back to MBS, which FTI does based on the timing of the video’s receipt and two messages that they claim “may reveal an awareness of private information that was not known publicly at the time.” One such message was the photo of the woman accompanied by the message about software licensing agreements, sent on Nov. 8, 2018. Somewhat inexplicably, FTI concluded that the woman in the photo resembled Lauren Sanchez, with whom Bezos was having an affair at the time, and was likely “sent with reference to Bezos’ personal life events at that time” because he was privately discussing a divorce with his then-wife but had not mentioned it to MBS.

FTI also cites a WhatsApp message from MBS to Bezos sent on Feb. 16, 2019, a few days after Bezos was briefed by phone about “the extent of the Saudi online campaign against him.” That message reads, “Jeff all what you hear or told to it’s not true and it’s matter of time tell [sic] you know the truth, there is nothing against you or amazon from me or Saudi Arabia.” The FTI report concludes: “this text evinces an awareness of what Bezos had just been told [in the briefing].”

On the one hand, the report paints a relatively compelling narrative of Saudi Arabia infiltrating Bezos’ phone, and on the other hand, the actual technical forensic evidence is fairly minimal. But perhaps the most striking thing about the report is the picture that emerges from it of Saudi Arabia’s cyber-espionage efforts, suggesting that the country is carrying out espionage efforts so openly and haphazardly that it does not really care who finds out about them and lacks any coherent strategy for conducting online surveillance or using the information it collects effectively. And regardless of whether FTI is right about all the specifics, this is a picture that largely aligns with Saudi Arabia’s previous cyber-espionage efforts.

Perhaps the best defense for Saudi Arabia—which has entirely denied any involvement in the breach of Bezos’s phone—is simply that it makes no sense to infiltrate a phone this way. Having the nation’s crown prince personally deliver malware to a target is careless enough, but perhaps MBS was the only person the Saudi government thought would have a sufficient personal connection with Bezos to exchange WhatsApp messages without inciting suspicion.

But to then follow up, from that same account, with weird memes and warnings is even more bizarre, much less to share stolen information with a U.S. tabloid, thereby drawing even greater scrutiny from Bezos and his security team. And to do all of that while still going to trouble of wiping the malware from the phone so it could not later be detected is even more confusing. It’s too small-scale and private an intrusion to serve as a public signal of Saudi Arabia’s cyber-espionage prowess, but too brazen and public to be any kind of attempt at long-term covert espionage activity.

But this weird behavior would also fit Saudi Arabia’s pattern of cyber-espionage in many ways. In a world where most online intrusions are meant either to serve as public signs of strength or covert maneuvers, this odd in-between type of not-quite-secret but not-really-out-in-the-open cyber-espionage is gradually becoming a hallmark of Saudi Arabia. For instance, last year the Department of Justice announced charges against two former Twitter employees for providing information about Twitter users to the Saudi Arabian government. That, too, was an odd case of Saudi Arabia doing something fairly overt and easy to discover but in a way that suggested they were mostly trying to collect information privately about Twitter users who had been critical of their regime. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s use of Pegasus spyware, sold by controversial Israel company NSO Group, to spy on the communications of journalist Jamal Khashoggi prior to his murder, indicate a government that is not particularly interested in hiding its cyber-espionage activity even when planning targeted, secretive operations.

The very carelessness of these efforts suggests that Saudi Arabia feels little pressure to hide its online maneuvers, that it views cyber-espionage as so common and so widely practiced and accepted at this point that there is no need to hide its tracks. Nor does it try to trumpet these espionage efforts as proof of its formidable cyber capabilities—indeed, most of them are not terribly technologically impressive. If the FTI report is accurate, the Bezos breach is notable for how brazen and bizarre it is as an act of espionage, and how confident Saudi Arabia apparently was that it could do whatever it wanted in this domain without facing any real consequences. If it’s not accurate then Bezos is dealing with a considerably more sophisticated adversary—one who was savvy enough to very effectively frame MBS and Saudi Arabia.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.