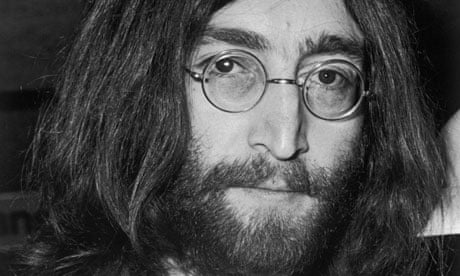

Poor John. He's got old Macca on one side, fruitlessly trying to reverse the hallowed songwriting credits to make it clear, in case there were any doubt, that he wrote "Eleanor Rigby" and forever claiming (with some justification) that, of the two creative pillars of the Fab Four, he was the one who was really interested in the avant garde. On the other, there's old Yoko, flogging off his image to motor manufacturers and fountain pen makers and adding ludicrous credits to his albums (on my CD of Rock 'n' Roll, the oldies album John recorded in 1973, with and without Phil Spector, it actually says: "Production personally supervised by Yoko Ono").

And in the middle there's Julian, his son by his first wife, already – can you believe this? – older by seven years than John was when Mark Chapman fired the fatal shots, emerging to complain about the cost of collecting memorabilia connected with a father for whose prolonged absences during his childhood a legacy reputed to be £20m appears to be, understandably enough, scant compensation.

In two weeks' time, on 9 October, John would have been 70. On 8 December, it will have been 30 years since his death. The remains of the record industry he helped create, its pistons still warm from the fevered launch of the Beatles Remasters series and the Beatles: Rock Band video game a year ago, is cranking itself up again. Next week, the troubled EMI Music will put on a happy face and issue not just remastered versions of eight existing Lennon solo albums, but a bunch of new compilations and boxes, squeezing yet more blood from the carcass of the group whose phenomenal success brought it the prosperity that has subsequently been frittered away.

Yoko has been heavily involved in all this activity. How could she not be when a line on the cover of all the reissues of her late husband's work states: "The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Yoko Ono Lennon/EMI Records Ltd"? Much more satisfactory, of course, to have it owned by the widow and the original record company than by some bunch of hustlers to whom the Rat Pack represented the pinnacle of 20th-century popular culture, which is what happened to the Rolling Stones' early recordings. If barrel-scraping has to be done, then better that the royalty cheques should be paid into a bank account bearing the name Lennon.

It was Yoko, however, who agreed to let an advertising agency working for the PSA Peugeot Citroën group buy the rights to a clip from an interview given by John in 1968, for use in a television commercial earlier this year. "Once a thing's been done, it's been done," the long-haired Lennon is saying. "So why all this nostalgia? I mean, for the 60s and 70s, you know, looking backwards for inspiration, copying the past. How's that rock'n'roll? Do something of your own. Start something new. Live your own life." The message: buy our "anti-retro" car, the Citroën DS3.

Except he was actually saying something else. A YouTube detective posted the original footage, shot by the BBC, in which John is actually talking about reading Sherlock Holmes in Tahiti before writing his own book, A Spaniard in the Works. The new words are from a different source and to anyone familiar with Lennon's speaking voice, it seems that they have been slightly slowed down to create an approximate match with the film.

Sean Lennon, his younger son, apologised for that one. Well, sort of. He tweeted in defence of his mother: "She did not do it for money. Has to do w hoping to keep dad in public consciousness. No new LPs, so TV ad is exposure to young. Having just seen ad I realise why people are mad. But intention was not financial, was simply wanting to keep him out there in the world."

Pull the other one, Sean. This is a man, your father, whose Wedgwood-style lavatory, originally installed at Tittenhurst Park, Ascot, his last home in Britain, was auctioned for £9,500 last month.

The last album he autographed – Double Fantasy, inscribed at the request of Mark Chapman a couple of hours before the 25-year-old returned to the Dakota building to make himself famous – went for $525,000 seven years ago. One of last year's most successful British films was Nowhere Boy, Sam Taylor-Wood's scrupulous and sensitive account of his early days. John Lennon's name is hardly one that needs to be artificially hoisted into the public gaze.

But that hasn't stopped his widow exploiting it in fields that have nothing to do with music. In the last couple of weeks, the Montblanc company has been promoting a John Lennon special-edition fountain pen, with a clip shaped like a guitar fretboard. The newspaper ad has a CND symbol in the background and a slogan: "To John, with love." An earlier pen was dedicated to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi, with a picture of the spiritual leader engraved on its 16-carat gold nib.

John would have laughed at that, wouldn't he? Perhaps with scorn, certainly with amusement at the incongruity of the project. But only diehard Beatles fans seem to be upset. The rest of the world accepts it as part of a new culture in which everything – particularly if it evokes a set of desirable values – is for sale, everything is negotiable, everything is there to be sampled and remixed and put to some new purpose.

Here is one of the many aspects of life that have changed since Lennon celebrated his 40th and final birthday. And here are some of the other things he missed. Madonna. Mike Tyson. Princess Diana, more or less from start to finish. Beverly Hills Cop I, II and III. The flowering of Thatcherism. The internet. The second summer of love. The Blair Witch Project. Grunge. The fall of the Berlin Wall. Nice girls wearing tattoos. Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig as 007. David Beckham. Gangsta rap. There's Something About Mary.

Dunblane and Columbine. World music. Tim Henman. The Oklahoma bombing and 9/11. The neocons and New Labour. Radiohead. The Asian tsunami. The iPod. Rom-coms and reality TV. Mamma Mia!. Auto-Tuning.

And Twitter, of course, to bring it right up to date. He would have loved Twitter. He was an inveterate sender of postcards, often decorated with doodled self-portraits, and he wasn't the sort of person to write a letter and then put it away in a desk drawer overnight before inspecting it the next morning and removing anything that might have been set down in haste. His generosity and his venom were equally impulsive in their nature and second thoughts didn't really interest him.

I happened to be there when he was learning to type, in the suite he and Yoko occupied in the St Regis hotel in New York as a temporary accommodation after making the move to the US in the autumn of 1971. He was sitting on their bed with a small portable machine on his lap, tapping away. One of the things he wanted to be able to do was type letters to newspapers.

My paper, the Melody Maker, subsequently became the recipient of several lengthy broadsides, usually disputing assertions made in interviews by Paul McCartney or George Martin. He saw everything and let nothing go without comment. Twitter's immediacy, and its encouragement of the urge to respond, would have suited him down to the ground. Once Sean had shown him how, you wouldn't have been able to get him off it.

But in what other ways would he have adapted to a changing world, had he not turned in response to Chapman's call that night on the corner of West 72nd Street and Central Park West, after being driven home from the Record Plant with a set of cassettes containing the fruits of that evening's work, his life about to come to an end only months after his re-emergence from half a decade of reclusion?

He was making music again, and although the songs on Double Fantasy could not match the riveting originality of "Norwegian Wood", "Strawberry Fields Forever", "Happiness Is a Warm Gun" or "I Am the Walrus", they were good enough to suggest that, once he had worked himself back into the groove, there would be better to come.

A new version of the album is among the latest set of reissues, stripped back to the original basic rhythm tracks and unadorned vocals and making it even more apparent that with these last songs, including "(Just Like) Starting Over", "Watching the Wheels", "I'm Losing You" and "Woman", he was consciously harking back to the music he loved in his early teenage years.

Rockabilly and doo-wop provide the sturdy structures, with a nod to the skiffle of the Quarrymen as he sings "Long, long lost John" over the fade of "I'm Losing You", in a deliberate echo of Lonnie Donegan's version of a song borrowed from Woody Guthrie.

Now, too, we can hear him prefacing "(Just Like) Starting Over" with: "This one's for Gene and Eddie and Elvis… and Buddy!" This was Lennon excavating his roots and he might have carried on with that for a while. He would certainly have admired the way some of his contemporaries make new music while retaining the integrity of the sounds that first inspired them. The chances are, however, that – after effectively missing out on punk and the new wave, which happened during his voluntary engagement with house-husbandry while Yoko worked at consolidating their fortune – he would have found a way to engage with more innovative sounds, rather than settling for the kind of traditional AOR textures that were added in the final stages of the production of Double Fantasy.

Not that he was ever a completely dauntless adventurer. For all his endorsement of Yoko's wailing, he cheerfully confessed that he had been unable to get through even the first side of John Coltrane's Ascension, one of the key works of the 60s avant garde. But having enlisted Phil Spector's help in 1969 to turn the reverb-laden sound of Elvis Presley's Sun records into the pared-back starkness of "Cold Turkey", "Instant Karma" and the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album, he might have found a way to perform the same trick for a second time at a later stage in his life. There is always an audience for primal, bare-bones rock'n'roll, something for which he had an instinctive feel.

In the Britpop wars, he would probably have preferred Blur's originality to Oasis's revivalism ("So why all this nostalgia? I mean, for the 60s and 70s, you know, looking backwards for inspiration, copying the past. How's that rock'n'roll?"). It's easy to imagine him enthusing over Radiohead and the White Stripes.

Contemporary R&B would have been another matter. To Lennon, R&B was James Ray's "If You Gotta Make a Fool of Somebody", Chuck Berry's "You Can't Catch Me" and the Miracles' "You Really Got a Hold on Me". In a limo ride across London one evening in 1970, he was full of praise for Lee Dorsey's "Everything I Do Gonh Be Funky" and Ann Peebles's "I Can't Stand the Rain". This was the real stuff, the raw sound that had made a Liverpool teenager's heart beat a little faster.

His views on Auto-Tuning would have been interesting. Jack Douglas, the producer of Double Fantasy, in which John's songs were alternated with Yoko's, remembered barring them from each other's sessions, not least because John was unable to restrain himself from pointing out when Yoko was singing flat. But he was a big fan of something called ADT – automatic double tracking, a device which split a singer's voice in two to create the sort of effect that distinguished many pop records in the late 50s and early 60s.

If it made him sound like the records he admired, it was OK.

He had been away from England for almost a decade when he died and visitors from the old country were often regaled with his yearning for Chocolate Olivers. London certainly missed him. As long as the Beatles were headquartered at 3 Savile Row, with its parade of bizarre hangers-on, the city seemed to have a centre of vibrancy and an unfailing source of headlines. New York turned out to be a better place to live, but he had been bruised by the battle to obtain his residency permit and by the discovery that J Edgar Hoover's FBI had been watching him as a result of his association with the Yippies and the Black Panthers.

The brief flowering of a well-meaning but incoherent political consciousness seemed to have gone dormant in the last phase of his life; he had become suspicious of those who arrived proclaiming high ideals but wanted only to exploit his celebrity and perhaps grab some of his loot.

According to his most recent biographer, Philip Norman, his 40th birthday found him growing "increasingly nostalgic about his homeland, pining for British institutions and values he had so angrily spurned".

There was talk of returning on the QE2 for a voyage that would end with the ship docking in the Mersey. He even speculated that he and Yoko would spend their later years, after Sean had left home, living among the artists in St Ives. Perhaps he would have resumed the engagement with art that began at Liverpool College of Art in 1957, or found time to explore once again the love of surrealistic wordplay that crackled through In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works.

No doubt, some version of those notional events would have taken place. If all other lures had failed, the death in 1991 of his Aunt Mimi – the loving but stern Mimi Smith, his mother's sister, who brought him up from childhood through adolescence – would have drawn him to Poole in Dorset, where she lived out her last years in a bungalow paid for by a nephew who adored her despite that celebrated early warning: "Music's all very well, John, but you'll never make a living from it." Perhaps it was the formative supervision of the disciplinarian Mimi that gave him the habit of putting his trust, not always wisely, in strong, self-assured characters: Yoko, Spector, and the New York hustler Allen Klein, whom he brought in after Brian Epstein's death to sort out the Beatles' affairs, to McCartney's disgust.

And then there was George Harrison's death in 2001. Lennon and McCartney eventually settled their differences, major and minor, but as long as the four of them were still alive John always stood in the way of what he believed would have been the inevitable anticlimax of a public get-together with Paul, George and Ringo, even when implored by Kurt Waldheim, the secretary-general of the United Nations, to perform at a fundraiser for the survivors of the Cambodian genocide.

Loyalty to Yoko surely played a part in turning him against a project that would inevitably have reminded his audience of how much they missed the old relationships between the four musicians, before the arrival of powerful women pulled the two principal figures into a new phase of their lives from which retreat became impossible. Whatever else the future might have held, there would have been no Beatles reunion.

This article was updated on 28/7/10. The reference to a Mont Blanc pen was changed from £16,000 to 16-carat

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion