Watching television at his Boston home in January this year, Patrick Meier, a director of the crowdsourcing internet platform Ushahidi saw early reports that a devastating earthquake had caused massive damage to Haiti. Within 40 minutes, he was working with a colleague to set up a dedicated Haiti-focused website, and in less than an hour the site was gathering intelligence from people on the ground.

Ushahidi, a site created to document violence in the aftermath of Kenya's 2008 election, became a key portal for disaster relief agencies racing to provide assistance to Haitians. The site gathered text messages from trapped and stricken survivors and invited the vast Haitian international diaspora to help translate them from Creole and map the precise location of each eyewitness report.

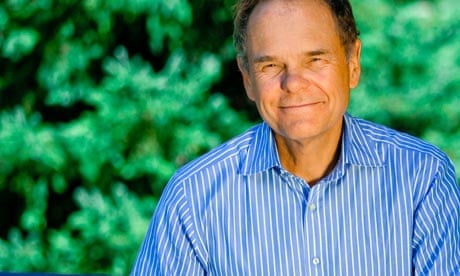

The ground-up, mass collaboration effort was the opposite of the usual global emergency response, which traditionally consists of sending in teams of experts to assess the situation and make quick judgments about the disbursement of help. It is the kind of example that Don Tapscott, a Canadian academic and business consultant, adores.

Tapscott and his co-author, Anthony D Williams, set the digital world aflutter with a 2006 bestseller, Wikinomics, which examined ways in which vast public participation could help businesses seize upon ideas and compete in the global marketplace. Now they are back with a follow-up that takes this concept and broadens it from business to more than a dozen other fields of activity – including healthcare, transport, education, finance, politics, media and music.

Falling apart

Called Macrowikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World, their new book is enormously ambitious in scope. But it is predicated on a somewhat apocalyptic view that the institutions of the developed world are falling apart at the seams.

"I don't think it's an exaggeration to say we're in the early stages of a profound change to civilisation," Tapscott says. "We're not just in the fallout from a recession. We're at a turning point where many of the mechanisms that have served us well are stalled."

The book gloomily ticks off a list of crises. Banks have been exposed, public finances are creaking, healthcare spending is soaring unsustainably, media companies are crumbling, mass unemployment is threatening welfare systems, a water shortage is looming and energy production is facing an environmental revolution.

Tapscott reckons we are in for an epochal shift: "The idea that we're moving from an industrial economy to a new age of networked intelligence has been around for a long time but there were ideas in waiting – and they were waiting for a bunch of things to happen."

The triggers, he says, are a well developed web, digitally literate populations, changes in the global economy and a "convulsive shock" to established systems that make us look twice at the presumed certainties around us.

Collaboration, according to Tapscott's thesis, takes myriad forms. In the healthcare world, patients have access to a vast store of online information to assess their conditions and can easily swap stories, tips and drug reviews with sufferers from the same illnesses. And the vast store of shared data can be cheaply and easily mined by the healthcare industry for new insights.

"The old paternalistic model, that 'I'm a doctor, I have knowledge that you don't, I'm going to deliver healthcare', is not going to work long-term. Rather than a mass produced, hierarchical, paternalistic, one-way model, let's move to a collaborative model that's open, where we can share," says Tapscott.

More or less the same goes for education, where swapped ideas, online tutoring and self-motivated research make learning far more individualised. Tapscott says: "The anecdotal evidence is very strong that in the US, the smartest students don't go to lectures. There are just better ways, better models, than pedagogues."

And then, of course, there is the newspaper industry, which is still casting around for a reliable way to make profits in an era where news is "commodified", instant, easy to find and generally free.

"News is a commodity – I don't need to buy the Wall Street Journal to get stock prices or to find out that [Hewlett Packard's chief executive] Mark Hurd has resigned," says Tapscott.

The "old guard" media, the book argues, have a "pretty predictable and even pathetic" record in digital innovation. He asks why Rupert Murdoch didn't invent the Huffington Post, or why the telecoms company AT&T didn't launch Twitter. The blogosphere, meanwhile, is beginning to show signs of commercial acumen: "Lots of bloggers, over time, make a good living – perhaps a couple of hundred thousand dollars a year from advertising."

There are exceptions. Tapscott praises the Economist, which still manages to convince readers to subscribe to its print edition in order to access content on its website: "People will pay for genuine value – in the US, if you want international news you pretty much have to subscribe to the Economist. Pick up something like the Denver Post and it's all about 'man bites dog'."

He also has warm words for the Guardian, which, he argues, is one of the few media organisations that "gets" the new era of collaboration with its strategy of mutualisation, encouraging broad participation to end the "us" and "them" of journalists and readers.

Instead of erecting paywalls around its journalism, the Guardian has gone in the opposite direction by encouraging third parties to license, remix and reshape its content, weaving it deeply into the fabric of the internet.

Music industry

"The Guardian's approach is going to be about experimentation, adjustment and readjustment," says Tapscott. But, he says, that is better than a futile effort to turn back the tides of change.

"The canary in the mineshaft is the music industry. The internet should have been the best thing that happened to them. All they needed to do was change their business model and make music a service, rather than a product," he says. "But they used a legal remedy to a business model problem and the industry that brought you Elvis and the Beatles is now suing children."

Tapscott is already facing criticism for taking a solid idea from his first book and stretching it rather too thinly in an attempt to apply it to everything in the human universe. In the Financial Times, the reviewer Richard Waters accused him of taking "interesting phenomena" but applying "a heavy dose of messianic fervour to produce an absolutist view of the future".

However, Eric Schmidt, the chief executive of Google, says: "Don Tapscott and Anthony Williams' insights about the power of collaborative innovation and open systems, and their call to 'reboot' our institutions – business, education, media, government – haven't come a minute too soon. Macrowikinomics inspires by chronicling these path breaking developments and pointing the way forward for all of us."

Other theorists, including Andrew Keen, the author of The Cult of the Amateur, have raised concern that Wikipedia-style collaboration could harm innovation, bringing activity down to an amateurish level of mass mediocrity.

Macrowikinomics is inspired by insights gained in research projects for corporate clients who have consulted Tapscott's firm, nGenera Insight, about collaborative business concepts. Tapscott cheerfully admits to its limitations: "We're not futurists. We're not trying to predict the future. We're just trying to show the contours of a new model."

MacroWikinomics, by Don Tapscott and Anthony Williams, was published in the UK by Atlantic Books on October 1