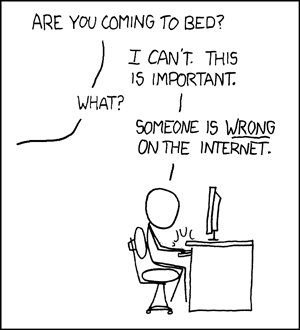

A copy of the famous xkcd comic "Duty Calls" hangs just outside my office door, signed by creator Randall Munroe. I didn't have to pay for the comic; it was free to view anytime, and I could have printed the (smaller) Web version if I desperately needed it on my wall. But xkcd is funny, Randall comes across as a good guy whose work I'd like to support, the print came signed on thick paper stock and printed at a higher resolution, and it was about $15. The real question isn't why I paid; it's why wouldn't I pay?

Munroe's approach to "protecting" his content might be best defined as "lenient."

"You are welcome to reprint occasional comics pretty much anywhere (presentations, papers, blogs with ads, etc)," he writes. "If you're not outright merchandizing, you're probably fine. Just be sure to attribute the comic to xkcd.com."

Somehow, giving the comic away for free has turned into a lucrative business for the now full-time cartoonist. While working on a piece this week about the online infringement lawsuit mill that is Righthaven/Las Vegas Review-Journal, I was reminded of the contrast that Munroe (and the many others like him) pose to more traditional attitudes to monetizing their creative work.

For instance, there's Review-Journal columnist Vin Suprymowicz telling a disappointed reader, "I don't think I will miss you. I have a far lower opinion of thieves than you appear to have. In fact, watching them copy my columns while interpolating their own content and pretending it's mine, watching them throw small merchants on the verge of bankruptcy by switching price tags and otherwise stealing merchandise below cost, I hate them with a passion. Lawsuits? They should have their godd**ned hands cut off and nailed to the wall of City Hall."

The contrast between the two could hardly be more stark. Munroe's model won't work for everyone, and creators should be free to choose which of their legal rights to exercise without those decisions being made for them by fans and pirates.

But every time I walk past my signed xkcd print, I'm reminded of what a disruptive influence the Web has been for creators. While the Review-Journal feels like it needs to sue its own sources in order to stay afloat, people like Munroe are happily giving up their content... sometimes even without ads. And they're doing fine. So is "content" itself doomed by the digital world? Are we left only with amateur creativity? Or is it only certain business models that are fading?

Chicken Littles

The xkcd print and the Righthaven story together put me in mind of a recent paper (actually, a transcript of a talk) by Mark Lemley, a Stanford Law professor and nationally noted expert in copyright and intellectual property. Lemley brings together newspapers, xkcd, photography, the photocopier, the VCR, digital audio tape, MP3 players, and the gramophone to make an argument about content production in the digital age: it's changing, not dying. Far from falling, the sky is holding firm.

Lemley's talk is colloquial; the language of the law review is (blissfully) absent. Some of it may be a bit over-the-top (do any content owners really worry that "no one is going to create new music anymore"?), but his main point is spot on: the sky may indeed be falling on a particular form of business model or even a particular form of creativity, but creative production itself has never been more robust. And, what's more, this has always been the case. Yet art and creativity survive.

"I sometimes suspect there was an association of monastic scriveners who protested the printing press on the theory that it was going to destroy the beautiful hand illumination of manuscripts," he says. "Which, of course, it did. But, it did not, as a result, destroy the book industry. In fact, it rather expanded that industry."

Lemley gives example after example of this trend. Broadcasters opposed those rogue cable operators when they first appeared; now they demand carriage. The VCR, opposed as a "Boston strangler" of the movie industry, became a huge cash cow, one milked for decades by that same industry. Radio's free broadcasts would destroy recorded gramophone music; except that the radio actually became one of recorded music's most important publicity machines.

Lemley isn't trying to sell anyone false comfort. Things might not be all right for many established businesses. But creativity carries on.

The content industry "has a Chicken Little problem," he says. "It may, in fact, be the case that the sky is falling. But, if you claim that the sky is falling whenever a new technology threatens an existing business model, the rest of the world can be forgiven for not believeing you when you claim that this time around it's going to be different than all of the other times. Now, let's be clear, each one of these technologies changed the business model of the industry. They caused certain revenue streams to decline. But they also opened up new ones."

Lemley cites xkcd as a perfect example of these new models, something that succeeds even as traditional newspapers flounder in search of a voice and a revenue stream.

There's no call for Web-native operations like Ars or xkcd to get cocky, of course; the wheel of fortune revolves, and someday all of us will be the old-school media operations, disrupted by—well, who knows by what? That's the nature of disruptive innovation. But as for creation, it will continue.

"I don't know exactly how it will turn out, what the future of the content industry will be," Lemley concludes. "But I am quite confident that there will, in fact, be one."

reader comments

136