How to Parent an Olympic Athlete

A new book gathers tips from a town that’s sent a competitor to almost every Winter Olympics for the past 30 years.

Watching a kid’s (usually mediocre) school piano recital can be enough to elicit in her parent a range of emotions, from fear to excitement to overflowing pride. What happens when the big event is not a rec-room recital but, say, the Winter Olympics?

Being the parent of a competitive athlete comes with all kinds of pressures. But Karen Crouse, a New York Times sports writer who has attended around ten Olympic games over the past few decades, stumbled upon a kind of parenting utopia where, in her view, parents are really getting it right. That utopia is Norwich, Vermont, a charming town with roughly 3,000 residents. It has a historic inn and spotty cell service; households’ groceries are added to a running tab that families pay off at the end of the month. But Norwich is big in other ways: The town has sent an athlete to almost every Winter Olympics over the past 30 years, and it boasts three Olympic medals.

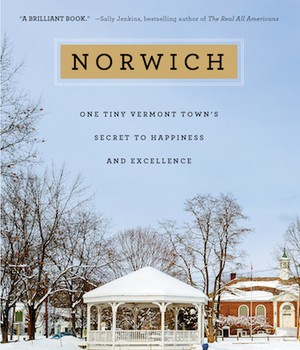

After covering the Olympics for so many years, Crouse grew tired of the games’ intense competitiveness and felt nostalgic for the more convivial ethos on which the games were founded. As Pierre de Coubertin, who founded the modern Olympics in 1896, said, in Crouse’s paraphrase: “the most important thing was not winning but taking part, just as the essential thing in life was not conquering but fighting well.” She found in Norwich a similar kind of grounded approach that she discovered was key to raising healthy and happy kids—many of whom would also end up excelling in competitive sports. Crouse is out with a new book on the town and its lovable residents—Norwich: One Tiny Vermont Town’s Secret to Happiness and Excellence. I asked Crouse about Norwich, the challenges of raising kids who play competitive sports, and whether this New England parenting utopia holds lessons for parents everywhere. Her answers, provided via email, have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Isabel Fattal: What role do parents play in their kids’ Olympics experiences? Do parents usually come to the Olympics?

Karen Crouse: Few people know this, but parents of Olympians do not have ready access to their children during the Games. I’ve watched swimmers converse with their parents through a chain-link fence because ... of tight security measures that are in place. And the athletes’ days during their competitions are so regimented they don’t have a lot of free time until they’re done competing to hang out with their parents. Sometimes the athletes would have a hard time spotting a familiar face in the stands. The parents are often relegated to the nosebleed seats because their children didn’t secure their Olympic spots until weeks before the start of the Games … or because they’re settling for the most inexpensive seats as that’s all they can afford.

Fattal: You write of the parents of the mogul skier Hannah Kearney and the pro-hockey player Denny Kearney that their “greatest contribution to their children’s sports careers was simply showing up.” Yet some people might say that good parenting involves pushing kids to remember their goals and dreams at times when they lose focus. When it comes to parenting kids who are involved in something as stressful as competitive sports, where’s the line between supporting their ambitions and not pushing them too hard?

Crouse: From fleshing out the stories of the Norwich Olympians, my rule of thumb for parents would be this: If your child needs help remembering their goals and dreams at times when they lose focus, that could be a sign that they have lost their passion or enthusiasm for the sport. [The kids I wrote about in the book] never needed to be reminded of their goals. They woke up every morning thinking, “How can I get better today?” Parents who give their children ownership of their sports careers, who are content to ride shotgun for the journey—however long it lasts and wherever it leads—never have to fret about separating their ambition from their children’s ambition. They need not worry that they’ve crossed the line between supporting their children to pushing them.

[The Kearney parents] got in that passenger seat for every mile of the journey—but [they were] never the ones behind the wheel, dictating the path that Hannah took.

Fattal: What do you think makes the schools in Norwich most unique? Are there lessons other schools can adopt to better balance rigorous sports with student health and well-being?

Crouse: A good start would be no-cut recreational leagues, which send the message that there is a place for anyone in sports and not just for the most skilled. Sports at the youth level should not be the province of only the very best. In a child’s formative years, the intrinsic benefits of sport far outweigh the extrinsic rewards—the trophies and medals and records. Sports is a vehicle to learn life skills like self-discipline, teamwork, perseverance, goal-setting, delayed gratification, and risk-taking. It is a vehicle to develop a lasting love for physical activity and the great outdoors and form enduring friendships.

Fattal: The experience of growing up in Norwich seems to be unique in that the town itself sort of parents the children. Do you think it’s possible for some of Norwich’s child-rearing tricks to be incorporated in bigger and less personal settings?

Crouse: Norwich is overwhelmingly white and mostly middle class, but the town’s child-rearing philosophy can be replicated in any community with parents, coaches, and administrators committed to following a few simple principles: Treat your neighbor’s child as your own (in Norwich, parents are invested in everybody’s children, not just their own. They foster an environment in which the success of one child is celebrated as a victory for everyone); frame sports as a really fun thing for your children to do on their way to longer-lasting achievements rooted in education; give children ownership of their activities.

Fattal: You mention in the book that many adults in Norwich trade treadmills for nature walks and other, more “grounding” sorts of activities. Did you see a clear correlation in Norwich between parents’ mental health or habits and the outlooks of their kids?

Crouse: There is really no way to gauge people’s mental health ... But I can say this: The parents I observed in Norwich make a concerted effort to be the people they want their children to become. They model kindness, compassion, and volunteerism; keep physically active; and place a higher priority on connecting to nature and the outdoors and to one another than to technology. One small example of the Norwich way: Parents regularly stop in at the school and volunteer to read a chapter or two from a paperback book of the teacher’s choosing to the younger classes while they eat lunch. I know because I did this a few times while I was living there. Then there was the example of the benefactor who helped a teenage Hannah Kearney cover her skiing expenses. He asked two things of her in return—that she provide him with a copy of her report card each term and that she break down how she spent the money. Hannah said it wasn’t lost on her that he didn’t ask for her skiing results. She realized he was sending her a clear message that her education is more important than her skiing while helping her to appreciate the value of a dollar and learn how to budget her money. Again, he was instilling in her the habits and values that he deemed most essential.

Fattal: Often, being around other ambitious people can help kids find their own ambition. Norwich seems like a place teeming with ambition, but a quiet and slow-moving kind of ambition. Do you think the slower pace of Norwich is challenging for kids who aren’t very self-driven?

Crouse: I would suggest that being around passionate people can help kids develop their own passions, and Norwich struck me as a place where people’s passions are supported and celebrated. Their kids are self-driven because the parents let them take the wheel of their lives and choose which path, or paths, they want to take. They will offer direction from time to time, but they aren’t providing the road map. The result is there is a place for the kids who like a sport like skiing because they enjoy being outdoors and want to be part of a group activity, and there is a place for kids who are more competitive and really, really enjoy the racing piece of it. Different strokes for different folks—the Norwich parents embrace both models with equal enthusiasm. They don’t see the point of one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter childhoods when no two kids are exactly the same.

The parents of Norwich are not setting out to develop Olympians. Their aim is to use sports as a vehicle to instill in their kids a lasting love of the outdoors and physical activity, learn life lessons, and develop lasting friendships. They recognize that in the big picture, relationships matter more than championships.