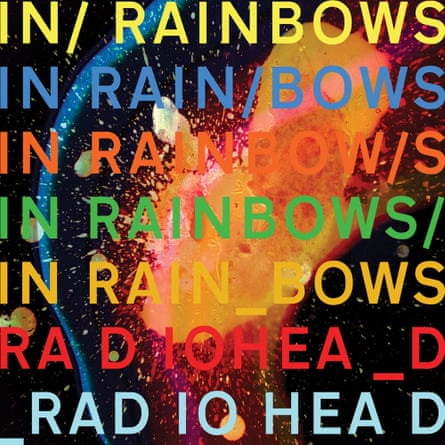

On Sunday 30 September 2007, just hours before the calendar flipped into Q4 and marked the start of the major labels’ busiest and most profitable retail period, Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood posted a message on the band’s Dead Air Space blog. “Hello everyone,” he wrote. “Well, the new album is finished, and it’s coming out in 10 days. We’ve called it In Rainbows. Love from us all.”

This seemingly blasé post to announce their seventh studio album was followed up by the details of the release. When it became clear what precisely they were doing, all hell broke loose – not just within EMI but across the entire record business.

In Rainbows would be available, with no record company involvement, on 10 October directly from their official website and fans could choose how much, or how little, they wanted to pay for the download version. The band had seen out their six-album contract with Parlophone with the June 2003 release of Hail to the Thief, but the long-serving executives at EMI who had backed them since the early 1990s had regular communication channels running with the band and their two managers – Bryce Edge and Chris Hufford of Courtyard Management – and were working out ways for Radiohead to renew their contract and stay with EMI.

Tony Wadsworth and Keith Wozencroft – the EMI executive who had originally signed the band 16 years earlier – were the key contacts and would travel regularly to the band’s studio in Sutton Courtenay in the Oxfordshire countryside, as they had done for years, to hear songs and recordings as they progressed. They were not naive enough to think that the band were not going to be talking to other majors or even large independent labels (singer Thom Yorke’s solo album, The Eraser, had come out in July 2006 on XL Recordings and Yorke had a close relationship with Richard Russell, the indie label’s head), but they felt they had a bond of trust with the band. They also held their catalogue, which was to prove a hugely important negotiating chip.

Reliable sources say that Wadsworth had travelled to the band’s studio at the end of August to hear what everyone understood to be an album nearing completion and, as such, could have a release date some time in 2008. Wadsworth reportedly met again with Hufford and Edge around three weeks later to discuss Supergrass – another Oxford band they managed and who were also signed to Parlophone – as well as to catch up on Radiohead developments. So even as little as 10 days before the Dead Air Space blog announcing In Rainbows, EMI UK’s most senior executive was still working on an understanding that a deal could be done with Radiohead.

A source close to the developments and negotiations says that Wadsworth was phoned by Radiohead’s team the day before the blog posting and informed what the band were going to do. They were going to do this without EMI. This was no “surprise” release; behind the scenes it had been carefully plotted for months, yet few were allowed into the tight circle of trust that consisted mainly of the band, Edge, Hufford and Brian Message, the band’s business manager at Courtyard. The team, however, were forced to bring in Jane Dyball from Warner/Chappell, the publisher the writers in the band were signed to, in order to slice through a Gordian knot related to the performing rights for the album.

As Radiohead’s circle of trust were working furiously to clear the way for this ground-breaking and controversial release, in EMI’s minds, the band could remain one of their marquee signings. The news of In Rainbows, when it came, ripped through Brook Green [EMI UK’s west London office] like a dirty bomb.

“Tony was devastated,” says one senior source who had to help pick up the pieces in the immediate aftermath of the announcement. “Oh my God, he was devastated when he found out they were doing it a different way. They had been in negotiations and Tony was convinced they were going to sign a new deal with EMI. It was a massive kick in the teeth for him.”

Radiohead’s management team declined all approaches to be interviewed.

Talks between EMI’s new owners and Radiohead’s managers, with Guy Hands having visibility on the key negotiation points, ran into complications. The final meeting is understood to have hinged on two issues: the band’s digital rights and ownership of their catalogue. There was talk of EMI being in the running to have the full CD release of In Rainbows, but the band would retain all digital rights. This would, in effect, be a pressing and distribution deal, possibly also having EMI involved in the marketing and promotion. This was something that could have been worked with, but Hands dug his heels in over the catalogue. The band wanted everything back and Hands was not prepared to consider any reversion of masters.

No consensus had been reached yet, but Courtyard Management had, by this stage, made up their minds. Someone else was going to get to release the CD version of In Rainbows. They reportedly said they had lost all faith in EMI and thought that Terra Firma’s ownership of the company was going to be “a bloodbath”. They wanted no part of it.

Perhaps partly to appease staff worrying about what this would mean for EMI and partly to save face, given that negotiations with the band had collapsed, Hands sent a memo to all EMI employees about In Rainbows. This was subsequently passed to this writer. He argued that while some in the record industry had “expressed shock and dismay at this development”, he believed “it should have come as no surprise” to those working in the business. “In a digital world, it was inevitable that a band with the necessary financial resources and consumer recognition to be able to distribute their music directly to their fans would do so,” he wrote.

The memo ended by saying that EMI needed to lead the way for a record business that has “stuck its head in the sand” by properly embracing the digital opportunities, and to stop relying on CD sales. “Radiohead’s actions are a wake-up call which we should all welcome and respond to with creativity and energy,” he wrote. The subtext here was that In Rainbows, rather than being thought of as a defeat, should instead be thought of as a new type of opportunity. The optimistic took this as a sign of a company being fast to learn from its mistakes; the cynical saw it as little more than Orwellian doublethink. The CD edition of In Rainbows eventually went out on XL Recordings in December 2007, going to No 1 in the UK. It came out in the US in January the next year on TBD Records and also went to No 1.

Ed O’Brien, Radiohead’s guitarist, said they were “really sad” to be leaving the label that discovered them and turned them into one of the biggest bands in the world. He pinned pretty much all of the blame on the new owners in an interview with the Observer Music Monthly at the start of December 2007. “EMI is in a state of flux,” he said. “It’s been taken over by somebody who’s never owned a record company before, Guy Hands and Terra Firma, and they don’t realise what they’re dealing with. It was really sad to leave all the people [we’ve worked with]. But he wouldn’t give us what we wanted. He didn’t know what to offer us. Terra Firma doesn’t understand the music industry.”

Hands, however, maintains that this was about wringing as much money as possible out of their erstwhile record company. “They did it – they absolutely did it,” he says of their excessive financial demands. “They wanted a lot of money and we couldn’t make money on what they wanted. And they wanted their masters back, which we valued even more. At our valuation, it was millions and millions that they wanted. And we just weren’t going to do it. I think their view was that they wanted to do the experiment. I don’t think they saw it as an experiment. I think they thought it would work. I think they felt that if they were not going to do this then they needed a really big offer.” The fact these famous musicians were taking to the media to air their grievances against Terra Firma also caused consternation at the private equity company. “Guy took these comments from artists personally – like they were attacks against him,” says a well-placed source.

Exacerbating the already bad and very public situation, singer Thom Yorke waded in by posting a blog on the band’s website. In it, he denied that the band wanted “a load of cash” from EMI. “What we wanted was some control over our work and how it was used in the future by them,” he wrote. “That seemed reasonable to us, as we cared about it a great deal.” He claimed Guy Hands was not interested in striking a deal. “So, neither were we. We made the sign of the cross and walked away. Sadly.” He added with a flourish, “To be digging up such bullshit, or more politely airing yer dirty laundry in public, seems a very strange way for the head of an international record label to be proceeding.”

Tensions between the band and the new owners of their former label were about to get worse. Much worse. On 10 December 2007, EMI issued a box-set edition of the six studio albums it owned (along with an album of live recordings). They also issued a USB edition – a short-lived format that was briefly in vogue at the time – containing all their EMI releases. The USB came in the shape of a demonic bear face that had become a default logo for the band in recent years. The members of Radiohead were reportedly incensed at this as they had no creative input in the release.

More salt was to be rubbed in wounds the following June when EMI put out the two-disc Radiohead: The Best Of compilation. This, once again, enraged the band, partly because they had no input and also because a best-of is traditionally a last-gasp cash-in when a band’s career is in commercial and artistic freefall. The band felt this could not be further from the truth.

“It fucking pissed me off,” Yorke raged to The Word’s Andrew Harrison. “We could have taken them [Terra Firma] to court. The idea that we were after so much money was stretching the truth to breaking point. That was his PR company briefing against us and I’ll tell you what, it fucking ruined my Christmas.”

Rather than going out of his way to upset the band, Hands claims they had a simple economic choice to make: they needed to boost EMI’s revenues and, as they had the rights to Radiohead’s catalogue, it was inevitable it was going to be commercialised as much as it could be.

“They wanted money and they wanted control over their music,” is how he sees it. “Then they publicly go out and humiliate us. My view was, ‘Fine!’ The financial department came to me and said they could make X amount of money by just doing this. We put it on hold when we were having the negotiations with them. They asked me if I wanted to push the button on it or not. At the end of the day, it was my decision as to whether we pushed the button or not. I said, ‘We have a bank that is staring us down and now they have basically told us to eff off, I don’t think we have a huge amount of reasons to be nice to them. We need the money for the bank, so let’s do it [the reissues].’ So I took full responsibility and I did it. And if it spoiled his Christmas, I’m sorry! At the end of the day, I take responsibility for that.”

Anyone serving in the trenches at a record label for any length of time will warn you never to go to war with an artist in the press – even if they are demonstrably in the wrong. They will almost always have the public’s sympathy and the “suits” and “fat cats” of the music business will always come off worse. You let the artist have their say, you bite your lip and you hope the brouhaha subsides quickly. If anyone told Guy Hands this, he didn’t listen at this stage. He had become a storm chaser and EMI was driving right into a tornado.