An exhibition opening at the Munch Museum in Oslo this month, and at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in the US in November, finally answers the question John B Ravenal was asked many times over in the years he worked as a curator.

What was the connection between two artists as apparently different as Edvard Munch and Jasper Johns – the creator of The Scream, and the pioneer of abstract expressionism – and why had they given almost the same title to paintings separated by 40 years?

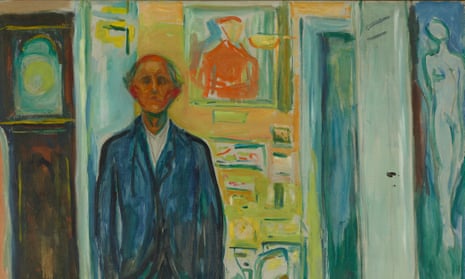

The Virginia Museum owns the fine three-panel work by Jasper Johns, Between the Clock and the Bed, painted in 1981, and it was Ravenal who put a little postcard reproduction beside it of the 1940-3 painting by the Norwegian artist, Self-Portrait Between the Clock and the Bed. But every time he walked through the gallery, he had to explain the link to baffled visitors struggling to spot any connection beyond the titles.

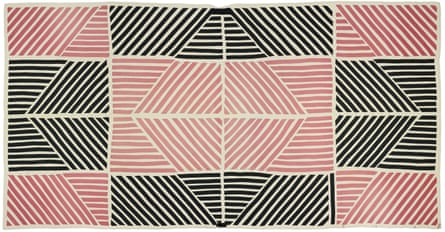

The sharpest-eyed might have spotted the cross-hatching of the Johns is almost identical to the pattern of the thin summer bedspread on Munch’s desolate and skeletal-looking bed – and visitors to this new exhibition can see the original coverlet, found in the Norwegian museum’s stores by researchers.

The art history legend is that a friend of Johns saw the Munch painting in Norway, and sent him a postcard because he spotted the similarity between the bedspread and John’s trademark cross-hatched paint strokes. In fact, Ravenal – now director of the deCordova Museum near Boston – believes that Johns had already seen the painting in an exhibition in 1950, and had been interested in Munch’s work for many decades.

His exhibition teases out many echoes between the artists. Ravenal asked Johns about the clock and the bed, and the artist, famously reticent to reveal any psychological insight into his work, said he was interested in painting objects positioned between other objects. Asked once about knives and forks and other kitchen implements in some of his work – they also appear in another grim Munch self-portrait of the artist about to tackle an entire cod’s head – Johns said helpfully: “My associations, if you want them, are cutting, measuring, mixing, blending, consuming – creation and destruction moderated by ritualised manners.”

Ravenal asked in Oslo about the bedspread, having seen an old photograph proving that at some point it was on display in the museum. Some staff thought that it had gone back to the Munch family; others that it had been a replica.

But an extensive search in the museum stores turned up the real thing, still in remarkably good condition and instantly recognisable from the painting, with a provenance showing it was the original. It will be a star exhibit in both museums.

Ravenal thinks both artists’ paintings are about sexuality and mortality, subjects much on the minds of both men – explicit in the Munch work, with the painting of the nude girl hanging by the bed, and the coffin-like clock measuring the remaining time, but also lurking in the shadows of the Johns.

“If the story of the postcard is true at all, it certainly came late in the process,” Ravenal said. “The connection was already there. Sex and death.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion