Predictions

A wrote blog post over on Medium musing on Predictions.

Quantopian and Steve Cohen

Quantopian has a big announcement today. The company will manage up to $250 million of investment capital, provided by Steve Cohen.

The investment capital will be allocated to members of Quantopian who create successful trading algorithms on the Quantopian platform. The algorithm authors own all their own IP and are paid a royalty if they decide they want to accept investment capital to power their algorithm.

The WSJ has more details. My favorite pull quote from the article is where they describe the backgrounds of successful algorithm authors:

[T]he creators of winning algorithms include a mechanical engineer with a Ph.D. in computational fluid dynamics in Sydney, a data scientist at an internet mapping company in Denver and a consultant in Malta with a master’s degree in mineral and energy economics

If you see yourself echoed in the description of these folks and have been curious about algorithmic trading, explore the community at Quantopian. You’ll feel right at home.

This is a huge milestone for Quantopian, and I feel privileged to have the opportunity to work with Fawce, Jean, and the rest of their incredible team on their journey.

Privacy Model for Notifications

We live in a weird new era where I nearly always have full control of what information I share and whom I share it with (assuming I have an indefatigable interest in navigating permissions settings for my various social services), but I have no control over my information once it leaves me. The consumption of my social content is entirely controlled by my followers, not me. This control model is simultaneously intuitive, correct, and disconcerting.

A classic example that comes up frequently for me is location. I’m perfectly fine with sharing my location with my friends through foursquare/swarm. I update Swarm multiple times per day and derive a lot of value from doing so. But I think it’s odd that, for people who have updates from me set to always notify them, some folks are constantly being reminded of my location, buzzing away in their pocket. This problem is not isolated to Swarm, it’s true for Facebook, Instagram, or any other means of sharing current location. I have no problem sharing this information, but I have a little problem with how “in your face” it can be under the most aggressive notification settings. It’s a vanity issue… I think my location is unimportant to the point that I’d rather it not be in my friends faces multiple times per day.

One could argue a few counterpoints:

(1) Why should I care how other people consume the content I create? Their mode of consumption is their choice.

(2) Just check-in “off the grid” more and share less.

(3) Just unfriend (most) people.

For me, (2) doesn’t feel like an option. I’m happy to share and when I get helpful comments about my location, it’s terrific.

If (3) is the answer, then the product is broken, not my usage. So, lets give well-intentioned designers the benefit of the doubt and toss out (3).

So, I think the whole meat of the issue is (1). I don’t want my friends to be able to control my notification settings, and yet, I wish I could control their settings when it comes to my content. My desire is obviously inherently contradictory and why I find it interesting enough to blog about. There is a difference between (A) sharing information such that others have opt-in access to it and (B) broadcasting information aggressively. Designing these settings (and their defaults) is really tricky, and I wish I could be a fly on the wall in these design meetings.

Bonus Corollary: Sometimes you send an email and instantly regret it. You want to edit or delete it, but you can’t. Your content is your own until you share it, and then suddenly it’s the recipient’s content too, as a received message and intuitive privacy controls implies that a recipient should control their content. Yet everyone has felt this exact email pain point, and so when Slack decided to design for this use case, they allow the author to both edit (with an “edited” sign next to the message) and also delete any message the author writes. Slack decided that tie goes to the runner and email decided that tie goes to the fielder. The email design decision is less intentional and more an artifact of the information architecture of how email works in a stateless distributed early-internet design (how can you take an email off a remote server you don’t own?), but it’s still an interesting design choice nonetheless.

The Unbiased Algorithm is a Myth

I published another longer read over on Medium. Syndicating here for Tumblr followers and email subscribers.

Related lazy-web request: does anyone know a good way to mix together the RSS feeds of Tumblr and Medium so that I don’t have to do these cross posts for my Feedburner email subscribers?

Corporate Governance: Dictatorships VS Democracy — Medium

I wrote a post over on Medium. It will be my new full time place for long form writing. I’ll probably continue to post more Tumblr-ish content here. Go follow me on Medium.

The Darwinism of Encryption (Or… Why It Doesn’t Matter If You Side With Apple or The FBI)

I’ve restrained my commentary on the Apple/FBI encryption debate to tweets so far, but I couldn’t find a way to say this in 140 characters, so blog post it is.

Digital communication is running a multi-decade inevitable march towards end-to-end encryption. In the beginning when the first ever TCP/IP packets were scooting around the ARPANET, all communication happened in the clear, unencrypted. There were no bad actors on the network; it was just a bunch of altruistic geeks freely routing forward each others’ packets (both academics and military, but all geeks nonetheless) cooperating together. After initial attacks against the network, it quickly became clear that one could not assume the man in the middle of your network path was your friend, and encryption started to emerge as a second layer of abstraction on top of TCP/IP (the military started first).

Fast forward to today, and much of the basic communication of average internet citizens are fully encrypted, without any knowledge or effort on their part. The Google search at the start of an average internet user’s session is encrypted by default, and Google now uses HTTPS encryption as a ranking signal; meaning they’re deliberately trying to send users to encrypted destinations, rewarding encrypted websites with more traffic than before.

This is not a pendulum that will swing backwards towards less encryption in the future. This is a forward march, in lock step with technical progress itself. And it’s a forward march taken at each step out of necessity. Continued innovation by hackers with increasingly sophisticated attacks is the fuel that feeds the progress towards more reliably secure communication.

In this light, the Apple/FBI debate is mostly moot. You could side with Apple and support their fight for privacy. Or you could believe the FBI’s intentions are noble and Apple is being obstinate for the sake of impractical ideals. Either way, we all will move towards more secure communication and the FBI’s demands of Apple are the latest spitfire of fuel into the combustion chamber of progress. Whether Apple does or does not comply, the public nature of this case has shown that the privacy of data we presume to be locked down properly in our devices is at risk. It’s secure enough to create a public debate between Apple and the FBI, but it’s clearly not secure against Apple itself. Apple is concerned about setting a “dangerous precedent” by complying with the FBI’s court order, but by virtue of Apple’s response alone, it’s now public knowledge that Apple can defeat its own security (regardless of whether they comply), and this knowledge will generate open source encryption innovation that will (on the longest time horizon) make all our digital communication more secure.

There is an analogy here in the history of online music piracy. Umair Haque has the perfect quote:

Every time the music industry kills an underground distribution channel, a more efficient one arises in its place. Goodbye mixtapes, hello www. Bye www, hello Napster. Bye Napster, hi BitTorrent. Bye BitTorrent, hi anonymous, ciphered, totally decentralized p2p nets.

Like the darwinism in file sharing, there is a darwinism in encryption technology. The FBI’s request could successfully generate the master access to Apple’s encryption they seek, but it will ultimately just generate an even more secure form of encryption that will be open, distributed, and not depend of the benovalence of a corporation. The government could take counter-actions to ensure that America doesn’t led the security tech march forward (by mandating government access to backdoors) or deem encryption of private citizens’ data illegal. But that won’t stop bad actors from using encryption; bad actors are already breaking the law, so what do they care about breaking the law twice? Encryption is here. It’s not a policy decision or a stylistic choice that will shift back over time; it’s math. We cannot un-invent it, and it’s only getting stronger.

Podcast with Nick Moran

Nick Moran keeps a great podcast about VC and startups called Full Ratchet (the name is in reference to a particularly thorny term in venture deals… I hope you never need to face it). He interviewed me a few weeks back, and Part I just went live today. Check it out. Part II coming tomorrow.

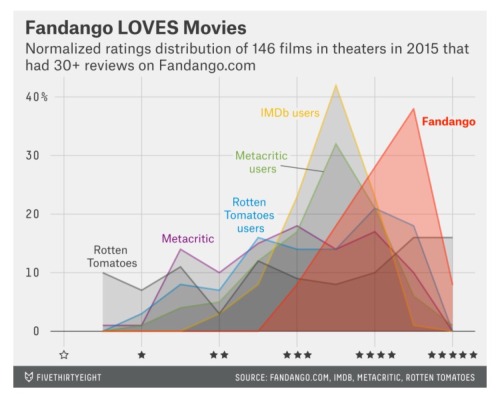

This chart from fivethirtyeight shows a histogram of movie reviews from 5 different sources. The reason they made this chart is to show that aggregated reviews on Fandango are skewed too high and thus untrustworthy (which is an appropriate conclusion).

But I find this chart interesting for a different reason. The disproportionate 3.5 star reviews from IMDB and Metacritic caught my attention.

My partner Mo once asked my opinion of something by saying, “What’s your rating from 1 - 10 in a world of no sevens.” I didn’t quite follow at first, but then he explained that a rating of “seven” in general is like a non-answer. It’s safely positively neutral in a way that contains very little signal. If you can’t say “seven,” but you think seven is what you would say, you’re forced off the fence into either a “six” or an “eight.” It’s a clever trick make ratings contain more conviction.

If I ran these movie review sites, I’d apply Mo’s system and ban 3.5 stars as a possible response, which would put a massive divot in place of the peaks in these two histograms.

Why Mobile-Optimized Works (pt 2)

Yesterday I wrote a post showing how companies’ mobile-optimized websites are generally better than their desktop websites when viewed from a desktop browser. It’s a somewhat dramatic conclusion to make given that companies usually have a comparatively rag-tag team focused on mobile-optimized design (all the mobile efforts typically get aimed towards App design instead of mobile-optimized design) in comparison to the richer and more established desktop design efforts. Why would the output of an afterthought team be better for a desktop than the hard-earned, constantly-A-B-tested, decade-long-work-of-love from the desktop web design team? I think there’s a few reasons:

- Constraints are good. When you’re designing for less screen real-estate, you are forced to make tough choices. For example, you can’t decorate the right rail of a webpage with 20 junk-drawer menu links on mobile because there isn’t enough screen real estate for a right rail at all. When you’re forced to design for 25% of the space, you are forced to decide what *really* matters.

- The mobile mindset is get in and get out. It’s not assumed that a mobile web session is going to be the start of a 30-minute rabbit hole of discovery. Instead, people landing on a mobile-optimized site are likely coming from Google and just need what’s on the permalink being called. A good mobile-optimized site serves this relevant information and very little else.

- Less ads. You can’t put 15 different banners interlaced in a poorly executed game of tetris above the fold when you’re designing for mobile because no one will ever trust your domain when they’re browsing from a mobile phone again. Less screen real estate corresponds to less intrusive ads.

- Whitespace. When you take a mobile-optimized site and you view it on a desktop, the various elements of the page scale up proportionally, including the whitespace. Whitespace is an absolutely essential design tool; the more of it you use, the more you can focus your user’s attention on what matters. If you want a button to grab your user’s attention, surrounding it with ample whitespace is your best tool. So, not only are their less competing design elements on the page in a mobile-optimized site, but the ones that did make the cut get a healthy dose of whitespace to amplify them when rendered on a desktop.

That’s my hit list. Add what I missed in the comments.

Mobile Optimized is the New Ideal Desktop Browsing Experience

When cruising through my Twitter feed on my desktop, I click on links that sometimes drop me on mobile-optimized pages. They are so much better designed than their desktop counterparts. These clicks inspired me to spend 5 minutes exploring the design contrasts at some of the most common sites I use.

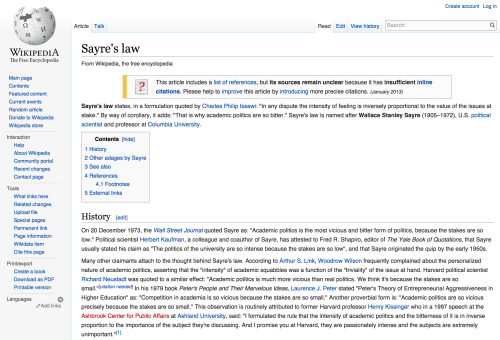

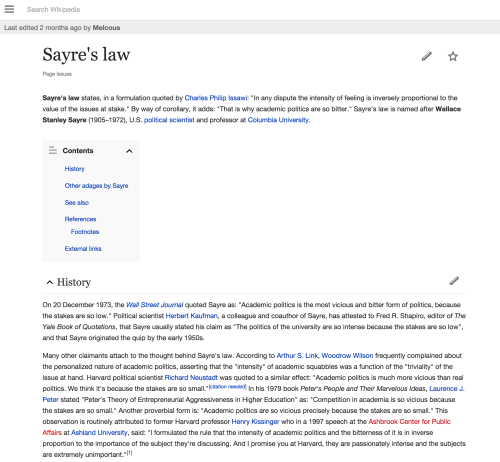

Wikipedia: Here’s the normal Wikipedia experience in my browser…

… and here’s the equivalent mobile-optimized Wikipedia entry as viewed from my desktop browser.

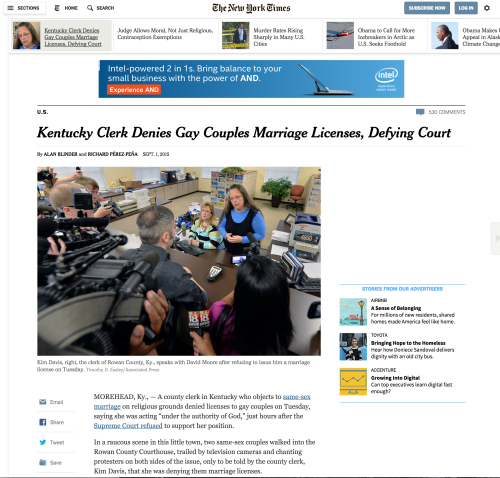

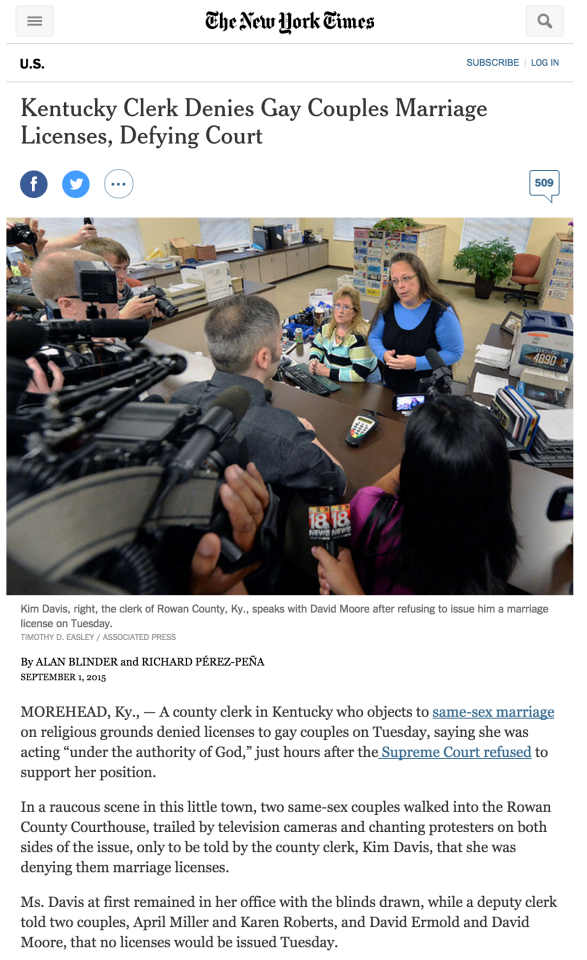

NYTimes: Here’s the normal NYTimes experience in my browser…

… and here’s the equivalent mobile-optimized NYTimes story as viewed from my desktop browser.

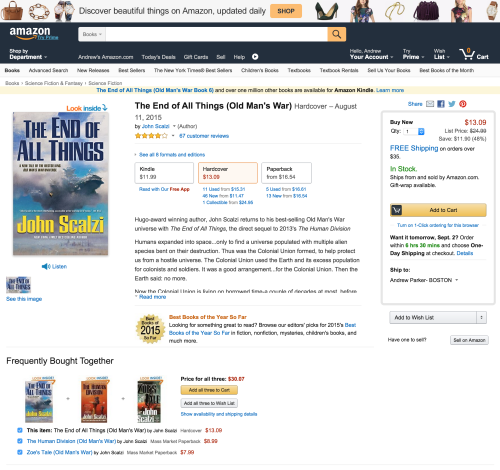

Amazon: Here’s the normal Amazon experience in my browser…

… and here’s the equivalent mobile-optimized Amazon product page as viewed from my desktop browser.

For this last amazon example, I couldn’t simply rewrite my url to visit m.amazon.com (which was my methodology for the first two examples). Amazon’s server-side logic was reading my user-agent and force-feeding me their crappy desktop experience. I had to send them a false iPhone 6 user-agent via Chrome’s Developer Tools in order to get a screenshot of what the mobile optimized experience looks like on a desktop browser.

The takeaway: All of these sites would be better served by simply throwing away their desktop optimized CSS and just serving the mobile-optimized experience to everyone. The mobile-optimized sites are simply better designed. Simpler, cleaner, better use of white space to focus attention. Unimportant options/links are all eliminated. Maybe I should just leave my user-agent as a mobile device permanently on my desktop.