Supreme Court Further Guts The Fourth Amendment

Yesterday the Supreme Court greatly expanded the circumstances under which police can rely on anonymous tips.

In addition to its decision in the Michigan Affirmative Action case yesterday, the Supreme Court also handed down a decision in Navarette v. California, and in the process once again did damage the rights protected by the Fourth Amendment:

In a case from Northern California, a divided U.S. Supreme Court ruled Tuesday that police can pull a driver over based on an anonymous tip that he had forced another motorist off the road – evidence, the court said, that he might be drunk and dangerous.

The 5-4 ruling upheld the convictions of two brothers from Mendocino County whose pickup truck was stopped by the California Highway Patrol on state Highway 1 in August 2008 after another driver called 911 to report that the pickup had just run her off the road.

After following the truck for five minutes, an officer pulled the driver over, smelled marijuana, and found 30 pounds of the drug in the truck bed, the court said. The driver, Lorenzo Prado Navarette, and his brother and passenger, Jose, pleaded guilty to transporting marijuana and were sentenced to 90 days in jail. They appealed, claiming the officer had no legal grounds for the stop.

California courts upheld the convictions, but the Supreme Court granted review to address two issues: whether an anonymous, uncorroborated 911 call is reliable enough to justify a vehicle stop, and whether being forced off the road is a sign that the other driver poses an ongoing danger, allowing police to stop the vehicle without any other evidence of wrongdoing.

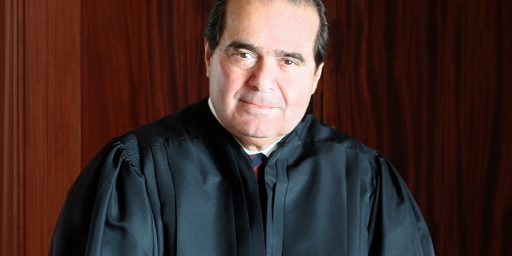

The majority, led by Justice Clarence Thomas, answered yes to both questions.

The caller’s description of the pickup and its license number, her use of the emergency calling system, and the CHP’s ability to locate the suspect vehicle 18 minutes after the 911 call were all indications that the information was reliable, Thomas said.

Running another vehicle off the road, he said, “suggests lane-positioning problems, decreased vigilance, impaired judgment,” all signs of drunken driving.

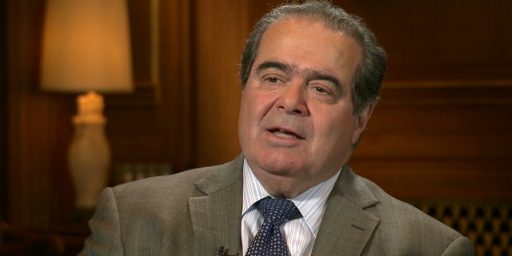

Dissenters, led by Justice Antonin Scalia, said anonymous accusations are inherently doubtful, and the caller in this case gave no indication that the other driver was drunk.

“The truck might have swerved to avoid an animal, a pothole, or a jaywalking pedestrian,” Scalia said. Even if the driver was acting recklessly or intentionally, he said, intoxication was an “unlikely reason,” and far too improbable to justify a vehicle stop.

“Drunken driving is a serious matter, but so is the loss of our freedom to come and go as we please without police interference,” said Scalia, joined by the more liberal Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. Thomas was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and fellow conservatives Anthony Kennedy and Samuel Alito, along with the more liberal Justice Stephen Breyer.

As Lyle Denniston notes, the majority opinion ended up giving police far more authority to act on the basis of anonymous tips than they had in previously:

The ruling in Navarette v. California, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, in part seemed to be based on prior understandings of when an anonymous tip gives police a valid basis for acting. But, as the opinion unfolded, it appeared that the Court had added significantly to police authority to conclude that they must act because a crime is in progress.

Here is the sequence that the Court followed to reach its result:

First, an anonymous caller telephoned police in Mendocino County, California, on the 911 emergency line to say that a driver had run her off the road. The caller described the truck and reported its license plate number.

Second, the fact that the tipster had used 911 added to its reliability, because new technology allows police to identify such callers, and go after them for false reports.

Third, the fact that the tipster had described a near-accident was enough to lead police to conclude that the other driver may well have been drunk.

Fourth, the suspicion of drunken driving, with the hazards that that poses for the traveling public, justified police in stopping the suspected driver even though, when actually following that truck, there was no erratic driving. The fact that there was no erratic driving was not proof that the driver was not drunk.

Fifth, on the suspicion of drunken driving, the officers were permitted, under the Fourth Amendment, to stop the vehicle. When they stopped it, they smelled marijuana, and they made a search that turned up four large, closed bags of marijuana in the truck.

All of those led ultimately to the conviction of two brothers, Lorenzo Prado Navarette and Jose Prado Navarette, on charges of possessing marijuana illegally. They pleaded guilty in a plea bargain, and were sentenced to ninety days in jail and to three years on probation. The conviction was upheld by California state courts.

And Ken White explains why this ruling is so novel, and so dangerous:

What’s novel here is that the majority agrees that reasonable suspicion can be premised entirely on a functionally anonymous tip. Traditionally the key to corroboration has been confirmation of incriminating details, not details that any observer could make about a innocent subject. So, for instance, if you call in an anonymous tip that I am running a meth lab in my blue house on the corner, and the cops confirm that I have a blue house on the corner, those details are not meaningfully corroborative. If the cops find evidence of witnesses seeing me move precursor chemicals into my blue house on the corner, that’s meaningfully corroborative. Here, the police observed no erratic driving or other corroboration of meaningful facts. In fact, they observed five minutes of unremarkable driving. The only corroboration was the innocent fact of the truck being present on the highway.

(…)

This approach renders the concept of corroboration almost meaningless by making calls to 911 about highway behavior effectively self-corroborating. If I want to call 911 and report that you are weaving in and out of traffic and appear drunk, under this decision, I just created reasonable suspicion to stop you. The cops can pull you over without observing you driving oddly at all — in fact, they can stop you even if they follow you for five minutes and you are driving perfectly.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the case is the fact that it placed Justices Thomas and Scalia on opposites sides:

The question before the Supreme Court was whether that single anonymous tip to 911 provided the police with reasonable suspicion to stop the truck. Writing for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas ruled that the “the stop complied with the Fourth Amendment because, under the totality of the circumstances, the officer had reasonable suspicion that the driver was intoxicated.” While this is a “close case,” Thomas acknowledged, it still passes constitutional muster. Joining Thomas in that judgment was Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, and Samuel Alito.

Writing in dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia came out swinging against Thomas. “The Court’s opinion serves up a freedom-destroying cocktail,” Scalia declared, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. It elevates an anonymous and uncorroborated tip above the bedrock guarantee of the Fourth Amendment. “All the malevolent 911 caller need do is assert a traffic violation, and the targeted car will be stopped, forcibly if necessary, by the police.” That state of affairs, Scalia declared, “is not my concept, and I am sure it would not be the Framers’, of a people secure from unreasonable searches and seizures.”

This isn’t the first time that Scalia and Thomas parted ways on Fourth Amendment cases. It also happened last year in Maryland v. King, in which a 5-4 majority that included Thomas upheld the right of states to collect DNA samples from criminal defendants before conviction without a warrant.

The Court’s decision in Navarette is remarkable in the fact that it make an anonymous tip about supposed erratic driving sufficient reason for a traffic stop even when the officer in question has not personally observed any such erratic driving. If the officer had received such a tip, located the vehicle, and then seen the vehicle driving erratically with his own eyes then, obviously, he would have been justified in making a stop. In this situation, though, the Court has ruled that a police office can base a traffic stop on information received from an anonymous person via another party (the 911 dispatcher) even though the officer has no reason to believe that the tipster is accurately describing the vehicle or even what happened. For all the officer knows, the tipster could have mistaken Navarette’s truck for another vehicle. Additionally, there might have been a perfectly innocent explanation for the supposed erratic driving, a supposition arguably supported by the fact that the officer did not personally observe any erratic driving even though he followed the vehicle for roughly five minutes. If someone is driving under the influence then, presumably, there would have been some evidence of it during that five minute period. However, even though the officer didn’t observe any such driving personally the Court has ruled that he can still initiate a traffic stop based on what someone he doesn’t know told someone else at some point in the past. That hardly qualifies as “reasonable suspicion.”

None of this should come as a surprise, of course. The Supreme Court has been chipping away at the protections of the Fourth Amendment, and providing more and more discretion to police and prosecutors, for nearly three decades now. The problem with cases like this, though, isn’t just the fact that they give police more authority to act outside the boundaries of the Constitution. These types of decisions also contribute to a general attitude among law enforcement that they can do whatever they wish so long as its in the name of “public safety. From reading the opinion, the Navarette brothers don’t sound like very good people, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have rights. The Court made a grave mistake here, and it’s one that we’re all going to pay for at some point.

Here’s the opinion:

Your homework for today: Find a single decision in which Clarence Thomas disliked a police action.

Fortunately, in the Supreme Court’s world, politicians never pay off their campaign contributors with beneficial policies and police would never never never never never invent an “anonymous tip,” knowing that they’ll never have to document it.

What a pity that most of us don’t have the money to live in this world.

So Justice Thomas is more consistent a conservative a$$hole than even Justice Scalia. Wow. Doug, remember when you argued that GHWB was our greatest living President? Care to now rethink that in light of his most enduring achievement-nominating Thomas to the SCOTUS?

@ Doug

You are the guy who could never vote for a Democrat. You’ve ceded power to these people. Really, what’s your beef?

Who could say this any better and more clearly (if not less bombastically) that Scalia?

Scalia needs to descend from his cloisters and get with the program.

As I’m constantly reminded by our state and city authorities, drivers have no rights, only privileges.

Oddly, while I’ve been lamenting for 20-odd years that we functionally no longer have a 4th Amendment, I’m not finding this particular ruling problematic.

I don’t want to live in a society with sufficient police surveillance that every action by every motorist can be effectively monitored by the state. Yet, I think there ought to be some recourse against dangerous drivers who in fact run others off the road, posing a threat to the public safety. The only conceivable recourse, then, is the 9-1-1 call by another motorist. Further, we have decades of precedent that severely limits the 4th Amendment protection of those outside their homes and, in particular, those driving a motor vehicle. While I’m uncomfortable with some of the rulings and outraged by others, I find unassailable the bedrock principle that a motor vehicle, which is after all by design mobile, should be easier to search than a home, which is typically stationary.

So, really, the 4th Amendment question at stake here is the anonymity of the 9-1-1 phonester? I can see some 6th Amendment arguments against the inadmissibility of such tips in court and would indeed lean towards excluding them outright as hearsay. But surely such a complaint constitutes reasonable suspicion to pull someone over and ask them some questions?

Anonymous 911 call? I didn’t think you could hide the source of a 911 call. You might not get the name, but in most cases finding out who called isn’t difficult. And why would it have to be specifically suspicion of inebriation, which no caller could prove? Isn’t insufficient care and control of a vehicle enough? It also relates to a regulated activity which is not a right. I’m not in favor of eroding rights and have a solid mistrust of authority, but there seems to be significant grey space here.

@James Joyner: Nothing wrong with calling 911 to report a dangerous driver. Last time I did it I identified myself.

Or to put it another way, why don’t I just go to the DMV find out your vehicle information and when you should be on your morning commute call in an anonymous tip on you. Sounds like a fun morning.

@James Joyner: “Yet, I think there ought to be some recourse against dangerous drivers who in fact run others off the road, posing a threat to the public safety. ”

Which is why, in previous rulings, the Court has had no trouble with the police following up an anonymous trip and observing the vehicle for evidence of impairment or other infraction. In this case the police followed a tip and found someone who was driving just fine and exhibiting absolutely no suspicious behavior. But pulled him over and searched him “because.”

That is the end of the fourth amendment. The police can now pull you over for no reason at all, as long as the claim there was a “tip.”

Good article, Doug. It’ll take another 35 years to untangle the drug exceptions mess from 4th Amendment jurisprudence 🙁

I fail to see why the 911 caller being anonymous has any relevance to the 4th amendment. Is a traffic stop based on an anonymous tip unreasonable when a stop based on a caller who leaves her name is reasonable? How does the status of the tipster have any bearing on our 4th amendment rights? Either the cops need some corroboration or they don’t.

Further, suppose a 911 caller reported a driver waiving a gun? Do the police then need to follow the guy until he commits some kind of violation before they can pull him over? Suppose someone calls 911 and reports that the driver snatched a kid off the street? Can the cops not pull the car over if the driver doesn’t commit a violation?

@Gavrilo: Because we have the right to face our accusers. If the accuser is anonymous how is the stop justified. If I was run of the rode and I said who I was I could stand in court and say, yes this is the person who wronged. In this case we have nothing, nobody to press charges or testify to a crime. No evidence even that there was a caller to begin with.

As briefly as possible, anecdata on Fourth Amendment erosion.

December 1973 A. Friend & two others parked their car & went over a cliff in a residential area in Calif. overlooking the Pacific, to smoke dope & watch the sunset. A house owner, allegedly fearing a fire hazard, called the police, who followed Friend &c., after they returned to their car & left the area, then pulled them over & arrested them for possession of well under an oz., between two of them.

Dismissed immediately on the first court appearance, the judge ruling there wasn’t sufficient & probable cause, although (unknown to Friend) it apparently was not unknown for hippies & students to stop there to do just what Friend was accused of, & Friend had indeed been caught w/ the goods.

911 calls are:

1) all recorded (at least in California they are)

2) and when made from a mobile phone, aren’t anonymous. They know the callers phone number and location at the time of call.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enhanced_9-1-1#Wireless_enhanced_911

These are different from an “anonymous tip” phoned from a pay phone in a crowded location.

My own experiences with mobile-based 911 calls (both as the caller, and as the first-responder being dispatched (volunteer firefighter)), is that the location accuracy is crap in rural areas, but often very good on the freeways of suburban and urban areas.

We have called the patrol a few times: an 18 wheeler driving erratically, weaving, slowing to 35 on the highway. In this case two cars were almost hit. The police said that several people had already called. A few miles later, they had the trucker pulled over. Another time a driver was weaving, driving slowly, then speeding up. They were a hazard to others and themselves. In these cases, I would think that the police would have cause to check for alcohol, drugs, or in the case of the truck; the weight and the driver’s papers.

Think about this: suppose a person is pulled over for a brake light being out. Is it ok for the police to look inside the car through the windows? I remember years ago there was a case where police found a kidnapped lady in the back seat during a license check.

I talked to a policeman a while back. He said that red cars get pulled a lot more than any other color. And if a woman or young person is driving that increases the odds a lot.

Around here if you get pulled for any moving problem (weaving, reckless, speeding, etc) you are going to have to walk the line to check for alcohol or other drugs. If they smell alcohol, you are definitely going in. Failure to take a breathalyzer test is automatic loss of license for a few months at least.

“Better safe than sorry”

“You’ve got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em” (Rogers)

Am I the only one here who thinks it matters that this all happened on publicly-funded roads, involving licensed (and subject to that responsibility) drivers?

If it had been some guy in his yard and an anonymous tip… that’s totally different.

@Aaron: It’s crap because they rely on tower pings to figure out your location. Rural areas have far fewer towers so finding your location is a bigger guess. This of course assumes you don’t have GPS or the 911 GPS option turned on.

Also you’re assuming someone isn’t using a prepaid phone or various methods to ensure anonymity..

@James: @wr: I get that there’s potential for mischief here. But it’s quite possible for a driver to have run me off the road and yet not be in the process of running someone else off the road when police observe him later. So, as long as you run only one or two cars off the road, it’s all good?

@James Joyner:

That depends. Are you OK we me and my buddies calling in bogus anonymous tips about your driving a couple of times a week, because you pissed us off once? Do you think those tips should be adequate basis for the cops to pull you over on your way to pick up your daughter from day care every time we call? To the cops, our word is as good as yours.

Of course, technology has already provided an answer here. There are no ‘anonymous’ 911 calls, which SCOTUS apparently doesn’t realize. Anonymous tips from pay phones (if there are any left) or prepaid cell phones can be legitimately discounted. Tips from real phones with identifiable callers are just as good as walking into a police station and making a statement.

@DrDaveT: SCOTUS does realize that 911 calls are not anonymous, and explicitly references that. The whole “anonymous 911 call” bit seems to be a failing of the original reporting, not a failing of the SCOTUS decision:

I think that is the key reason why they upheld it. It wasn’t an “anonymous” call, it was a report given to 911 via a mobile phone.