EDUCAUSE presents the top 10 IT issues facing higher education institutions this year. What is new about 2015? Nothing has changed. And everything has changed. Information technology has reached an inflection point. Visit the EDUCAUSE top 10 IT issues web page for additional resources.

By Susan Grajek and the 2014–2015 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel

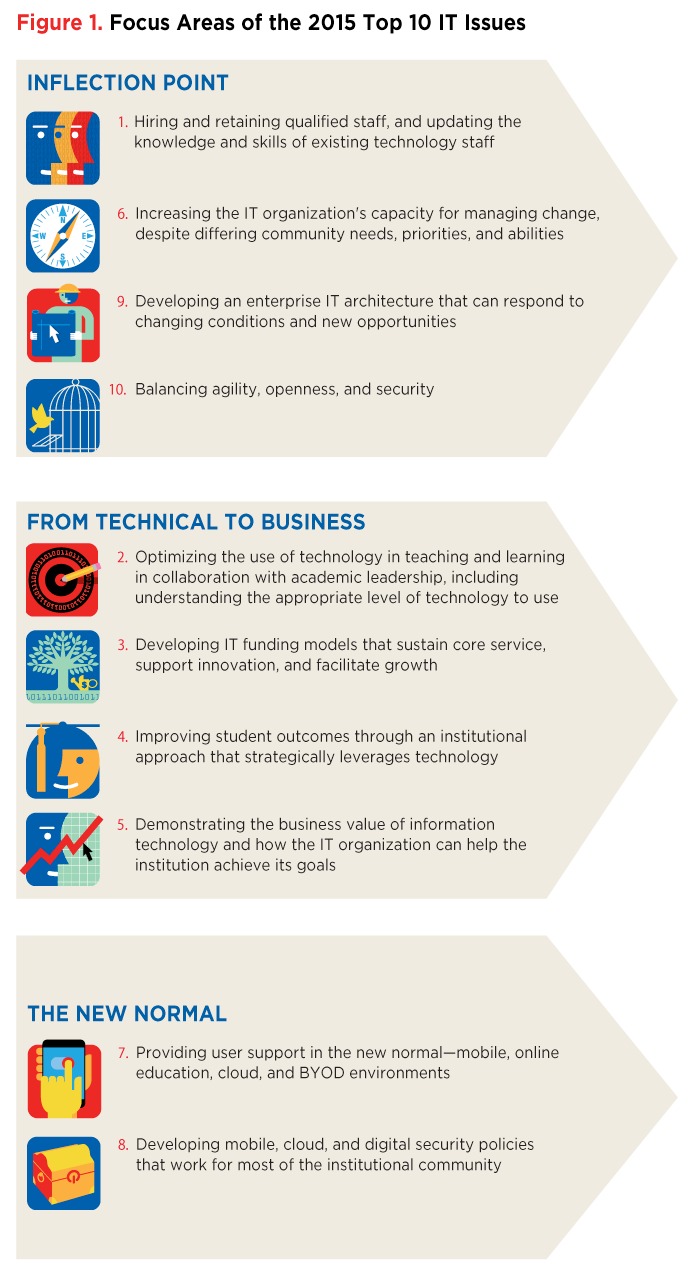

Change continues to characterize the EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues in 2015. The pace of change seems not to be slowing but, rather, is increasing and is happening on many fronts. There is reason to believe that higher education information technology has reached an inflection point—the point at which the trends that have dominated thought leadership and have motivated early adopters are now cascading into the mainstream. This inflection point is the biggest of three themes of change characterizing the 2015 EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues (see Figure 1). A second dimension of change is the shifting focus of IT leaders and professionals from technical problems to business problems, along with the ensuing interdependence between the IT organization and business units. Underlying all this strategic change, the day-to-day work of the IT organization goes on. But change dominates even the day-to-day, where challenges are in some ways more complex than ever. This "new normal" is the third theme of change.

Top 10 IT Issues, 2015

- Hiring and retaining qualified staff, and updating the knowledge and skills of existing technology staff

- Optimizing the use of technology in teaching and learning in collaboration with academic leadership, including understanding the appropriate level of technology to use

- Developing IT funding models that sustain core service, support innovation, and facilitate growth

- Improving student outcomes through an institutional approach that strategically leverages technology

- Demonstrating the business value of information technology and how technology and the IT organization can help the institution achieve its goals

- Increasing the IT organization's capacity for managing change, despite differing community needs, priorities, and abilities

- Providing user support in the new normal—mobile, online education, cloud, and BYOD environments

- Developing mobile, cloud, and digital security policies that work for most of the institutional community

- Developing an enterprise IT architecture that can respond to changing conditions and new opportunities

- Balancing agility, openness, and security

Themes of Change

Inflection Point

Change. It's a song that's been playing everywhere the last several years. You've been humming the tune, perhaps dancing to its rhythm. You may not know all the words, but everyone knows the refrain: "Mobile-Cloud-Big Data-Business Value-Agile-Transformation-Social-Analytics-Online Learning." Some people know just a verse or two, some know several, and some are even helping to write new verses. If change has become a standard, what is new about 2015? Well, nothing has changed. And everything has changed. Information technology has reached an inflection point.

Mathematically, an inflection point is a point of change on a curve in which the concavity reverses sign. Colloquially, the term is used to describe a turning point that results in extraordinary change. Andy Grove, Intel's former CEO, described a strategic inflection point as "that which causes you to make a fundamental change in business strategy."1

As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee assert in The Second Machine Age, this all comes back to Moore's Law, which posits a cyclical doubling of computing power.2 This doubling represents a rate of growth that is exponential. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of the power of exponential growth is Ray Kurzweil's concept of the second half of the chessboard.3 This concept is based on a legend about the invention of chess. When the emperor asked the creator of chess to name his reward for having invented the game, the inventor requested that for the first square of the board, he would receive one grain of wheat, two for the second square, four for the third square, and so forth, doubling the amount for each square. Kurzweil noted that although such an exponential growth pattern accrues only modest quantities at the beginning, when the second half of the chessboard is reached, the ensuing increases produce almost unimaginably large amounts. Viewing the impact of Moore's Law from this perspective, we can see that technology will at some point reach the second half of the chessboard. Brynjolfsson and McAfee posit that this has already happened, and they call it the second machine age: "Computers and other digital advances are doing for mental power—the ability to use our brains to understand and shape our environments—what the steam engine and its descendants did for muscle power."4 Analytics, cloud, mobile devices, social media, and online education might all be viewed as the fruits of the second machine age. IT architecture, process optimization, service management, and risk management are efforts to manage this overwhelming bounty.

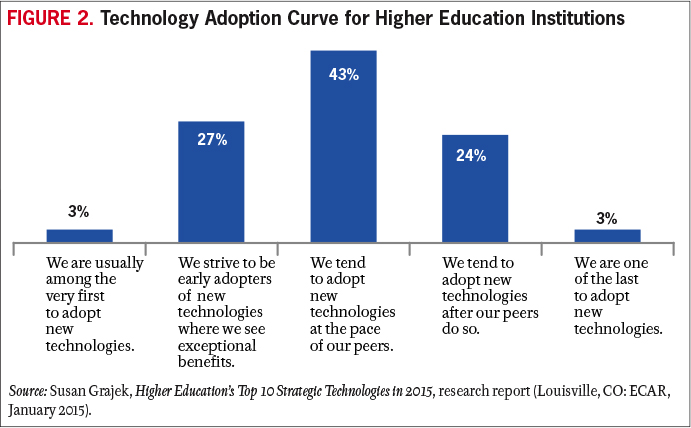

The second half of the chessboard is one reason for the inflection point we have reached. A second is related to the technology adoption curve. Individuals and institutions adopt technology at different rates: a few are on the bleeding edge, a few are the last to change, and most fall somewhere in the comfortable middle of the bell curve of adoption. The higher education community is no exception (see Figure 2). In Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore describes a pause or chasm between early adopters and the mainstream.5 An inflection point in adoption is reached when mainstream adopters cross that chasm and begin to enter a marketplace. As Moore describes it, they are motivated not by the desire to innovate (which motivates early adopters) but by the need to solve a problem that their current solutions cannot address, a need that activates an otherwise cautious group. When solutions become available that address their particular problems, members of that group will adopt new technologies.

The present inflection point in higher education information technology is likely due to improving solutions in cloud, analytics, bandwidth, and other technologies; very real problems of cost, productivity, and student success; and the useful examples and learnings of innovators among our highly collegial community. This inflection point is hitting IT organizations hard. As they stretch and struggle to help colleges and universities use technology to address challenges of student success, affordability, and accountability, IT organizations are retooling and restructuring to adapt to challenges of their own. Those challenges include ensuring a stable, qualified, and adaptable IT workforce and a clear and adaptable enterprise architecture. In both cases, "adaptable" means the ongoing ability to respond to changing technologies and solutions. Those changes are transforming both IT infrastructure, which is generally transparent to end users, and IT services and solutions, which are very much on the minds of end users and in the strategies of higher education leaders. IT organizations are struggling to manage both the pace and the volume of change on all levels. And anyone who has experienced a new system rollout knows how important good change management is to the success of an initiative. Managing information security in the light of ongoing new technology opportunities for both IT and higher education professionals presents another set of challenges.

Collectively, IT leaders and professionals may feel deluged by the volume, variety, and pace of change. In response to that deluge, many IT leaders are adopting a strategic approach to change through the use of frameworks for such activities as service management, vendor management, risk management, IT architecture, information security management, project management, process management, and capability maturity management. On the surface, frameworks may seem restrictive and bureaucratic, which accounts for the past reluctance by many in higher education to adopt them. However, at their best, frameworks can provide stability in times of change by creating replicable and scalable environments that can adapt gracefully to new and changing circumstances.

From Technical to Business

Bridging the gap between technology solutions and business problems is a challenge that many IT leaders are struggling to address. Moving from the role of technology leader to business leader is the second major theme of the 2015 EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues.

Perhaps most exciting, this theme highlights the challenge of delivering IT solutions that can address two of the most pressing issues in higher education: how to apply technology to teaching and learning, and how to improve student outcomes. To solve these strategic institutional problems, the IT and academic communities need to collaborate and cocreate. Each group has a different view of the problem, possesses different relevant expertise, and plays a different role in the solution. Further, many solutions that were previously accessible only to technologists are now available to end users, who are adopting applications with sometimes serious implications for information security, data management, and IT architecture. All this calls for the IT organization to recast its relationship with administrative and academic areas.

This second theme is also related to the need to reach across the white space in the institution's organizational chart so that the IT department better understands the needs of the institution and so that institutional leaders better understand the exciting potential of information technology and the time, resources, and executive commitment required to achieve that potential. The success and perhaps even the survival of higher education are more dependent than ever on technology. Members of the 2014 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel report that many institutional leaders believe that technology solutions are both easier and less expensive than they actually are. Because those executives are also increasingly interested in using technology to achieve strategic goals, many IT leaders are struggling to manage expectations without losing credibility or attention. On the other hand, some IT leaders are struggling with a different set of problems: how to communicate more effectively with institutional leaders and how to influence uninterested leadership.

Funding has made the EDUCAUSE Top 10 list every year. This year, the challenge with funding is to ensure that institutional leaders understand the need to fund the entire IT portfolio so that the IT organization is capable of supporting the aspirations, ongoing operations, and growth of the institution.

The New Normal

In the midst of so much change, challenge, and opportunity, IT organizations continue running core services and supporting end users. IT staff still go into fire-fighting mode more often than they would wish. But even normal operations are subject to the forces of change.

Most notably, bring-your-own-device (BYOD), digitization, and associated technologies and opportunities are changing the nature of user support and appropriate security policies. In the first instance, the IT organization needs to retool and redefine its support strategy. In the second, security policies must comply with regulatory requirements to protect data and privacy without hamstringing academics and administrators.

2014 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel Members

|

Mark C. Adams |

Vice President for Information Technology |

Sam Houston State University |

|---|---|---|

|

Mark I. Berman |

Chief Information Officer |

Siena College |

|

Christian Boniforti |

Chief Information Officer |

Lynn University |

|

Michael Bourque |

Vice President, Information Technology Services |

Boston College |

|

Karin Moyano Camihort |

Dean of Online Learning and Academic Initiatives |

Holyoke Community College |

|

Keelan Cleary |

Director of Infrastructure and Enterprise Services |

Marylhurst University |

|

Jenny Crisp |

QEP Director and Assistant Professor of English |

Dalton State College |

|

Patrick Cronin |

Vice President of Information Technology |

Bridgewater State University |

|

Lisa M. Davis |

Vice President for Information Services and Chief Information Officer |

Georgetown University |

|

Andrea Deau |

Director of Information Technology |

University of Wisconsin Extension |

|

Patrick J. Feehan |

Director, IT Policy and Cybersecurity Compliance |

Montgomery College |

|

Steve Fleagle |

Chief Information Officer and Associate Vice President |

The University of Iowa |

|

Tom Haymes |

Director, Technology and Instructional Computing |

Houston Community College |

|

Richard A. Holmgren |

Vice President for Information Services and Assessment |

Allegheny College |

|

Brad Judy |

Director of Information Security |

University of Colorado System |

|

James Kulich |

Vice President and Chief Information Officer |

Elmhurst College |

|

Jo Meyertons |

Director, Educational Technology |

Linfield College |

|

Kevin Morooney |

Vice Provost for Information Technology and Chief Information Officer |

The Pennsylvania State University |

|

Angela Neria |

Chief Information Officer |

Pittsburg State University |

|

Celeste M. Schwartz |

Vice President for Information Technology and College Services |

Montgomery County Community College |

|

Paul Sherlock |

Chief Information Officer |

University of South Australia |

|

Francisca Yonekura |

Associate Department Head |

Center for Distributed Learning, University of Central Florida |

The EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel comprises individuals from EDUCAUSE member institutions to provide quick feedback to EDUCAUSE on current issues, problems, and proposals across higher education information technology. Panel members, who are recruited from a randomly drawn and statistically valid sample to represent the EDUCAUSE membership, serve for eighteen months with staggered terms. Panel members meet quarterly for ninety minutes via webinar or in person. The meetings, facilitated by EDUCAUSE Vice President Susan Grajek, are designed as an ongoing dialogue to flesh out and refine an array of open-ended technology questions about the IT organization, the institution, and cross-institutional boundaries. The members discuss, refine, and vote on the most relevant underlying issues or options.

Issue #1: Hiring and Retaining Qualified Staff, and Updating the Knowledge and Skills of Existing Technology Staff

"We must be willing to combine some of the best benefits that business has to offer (e.g., flexible work arrangements) with the strong selling points of a career in higher education (e.g., connection with the mission)."

—Michael Bourque, Vice President Information Technology Services, Boston College

The long-held notion that information technology has three critical dimensions—people, process, and technology—is still true today. Behind every successful implementation of technology is a group of talented people ensuring that everything goes according to specifications to meet the needs of the students and faculty. Recruiting and retaining exceptional staff with the required knowledge, skills, and attitudes is not a small feat. Higher education competes for talent in an extremely competitive environment. The technology field currently has very low and, in some regions, virtually no unemployment. As higher education competes with all industries, those of us in academe are operating in an environment in which change comes quickly, whether in technology, business disciplines, or our core missions of teaching and research. To attract, maintain, and retain the necessary talent, higher education IT organizations need to adjust and adapt.

Today's IT workforce needs are different from needs in the past. We need a wide array of skill sets for roles that are evolving quickly. The field of information technology has always demanded that professionals retrain and retool to be able to design and support the latest technologies. Thus the ongoing evolution of technical skills is not new. However, the very models for providing and supporting technology-based services are in flux today. This set of changes requires staff to be not only adept at retooling but also capable of reinventing their roles. And those roles demand entirely new skills. To be able to deliver the technology solutions that students and faculty presently need while preparing themselves to lead the institution to adopt, innovate, or invent future technological advances, IT staff need such nontechnical qualities as initiative, grit, adaptability, and emotional intelligence.

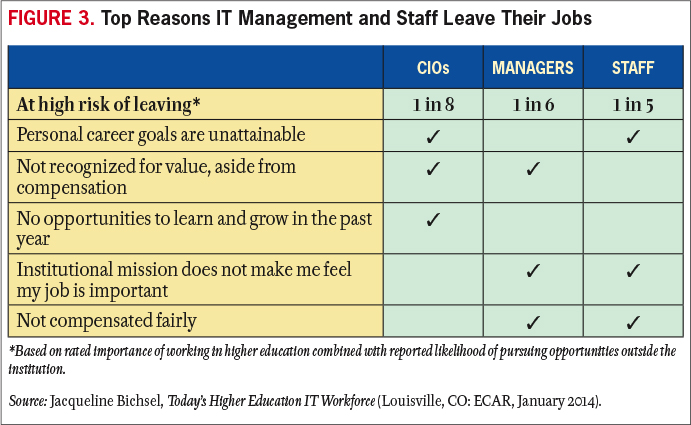

Retaining talented staff requires a culture of teamwork that supports and encourages the growth of the individual and the team. Management needs to foster a vibrant workplace in which diversity is valued and individuals feel respected. Management must also recognize that employees' views of satisfaction with their jobs are based on their collective experiences, ranging from salary to the culture of water-cooler discussions (see Figure 3). Leaders must remember that every employee has unique issues and methods of communicating, so at times, retention will come down to one-on-one discussions to understand employees' needs and to help employees understand their role in the larger IT and institutional strategy. Team members need to feel engaged with the organization and its mission, and they need to sense alignment of their efforts with something important (e.g., mission) to have a sense of purpose. With this sense of purpose, they are more likely to be committed to the institution. But with such long-term commitments also come the expectation of ongoing skill development and career advancement opportunities.

For performance management to be successful, it must become a critical and continuous part of the operations of the IT organization. Managers must ensure that staff are aware of their full benefits packages and of leadership efforts to provide a fulfilling and enjoyable work environment. Many institutions offer benefits and local area perks that employees are not aware of.

Augmenting the challenge of hiring qualified staff is the exponential speed at which technology is continuously changing. In light of this new normal, many current roles and even professions will not exist in the future. New roles and professions will arise to address changing technology delivery, pedagogical and research methods, and higher education business models. Not all staff will be able to recognize or adapt to these changes. Managers need to help staff recognize and prepare for new opportunities to minimize the disruption. Change affects not only the individuals who are disrupted but also those staff who are bystanders witnessing the change and anticipating the worst.

Fortunately, IT management is not without support. That support begins by building a partnership with the Human Resources department (HR). A success for the IT organization is a success for HR.

Advice

- Know how to sell the value of a career that contributes to the advancement of higher education and its teaching, learning, and research missions.

- Develop a list of the nonmonetary benefits of working for the institution and share that list with staff.

- Hire staff not just for their fit for the job but also for their emotional intelligence and fit with the values and culture of the IT organization and the institution. At the same time, remember that the strongest teams are those that are most diverse, so strive for a heterogeneous workforce that shares a common set of core values.

- Work with staff to select appropriate training. Funding and facilitating time for training and travel is only part of the process. Establish some deliverables and accountability for the training so that employees return to the office with the anticipated insights and skill set.

- Work with HR to develop career paths for the major divisions of or roles in central and distributed IT units. Careers paths don't have to stay within the IT organization; consider lateral paths that can broaden someone's institutional or business experience. Develop paths that reward knowledge work as well as managerial talent, and understand that not every staff member need aspire to leadership.

- Create a talent plan for the IT organization itself. Identify the skill sets and roles the organization will need to acquire and retire in the next one to three years. Create a roadmap to where the organization needs to head and begin working with HR now to implement the roadmap with as little disruption as possible for individual staff and operations.

Issue #2: Optimizing the Use of Technology in Teaching and Learning in Collaboration with Academic Leadership, Including Understanding the Appropriate Level of Technology to Use

"Faculty armed with current understanding and research on the power and value of technologies are more likely to use technology to enhance their pedagogical approaches."

—Celeste M. Schwartz, Vice President for Information Technology and College Services, Montgomery County Community College

Colleges and universities continue to invest in technologies in support of teaching and learning while struggling with ways to help faculty understand the value and potential impact of these technologies. An overlooked but critical starting point is for an institution to define its educational objectives and strategy. Institutions whose educational culture is intentionally and predominantly residential, ones that serve many part-time working commuters, those with strong global outreach, technological institutes, and institutions with strong practicum orientations may all grant similar degrees but will have very different pedagogical strategies and, therefore, different educational technology needs. Without a larger guiding vision, the application of technology to teaching and learning is neither strategic nor optimized; it is instead a series of endpoint solutions driven by individual faculty requests and by the best (often uncoordinated) efforts of service providers throughout the institution.

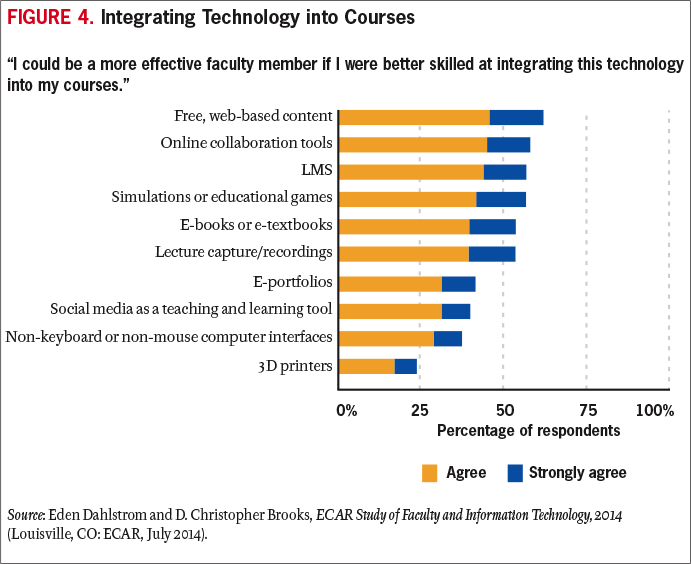

It is important to view technology as a supporting tool, similar to earlier tools such as blackboard/chalk. Technologies need to be carefully scrutinized for their pedagogical implications. Although online courses offer the allure of convenience and the opening (and thus increasing) of enrollments to students who might not otherwise be able to attend college in a traditional manner, their pedagogical effectiveness should be assessed as carefully as that of traditional classroom courses. Doing so might identify gaps in overall pedagogical assessment at an institution and thus improve even face-to-face learning. The real value of technologies is how faculty integrate the technologies into their teaching and learning and how they use the technologies to further refine their course delivery and student engagement (see Figure 4).

If institutional leaders become more intentional about their pedagogical objectives and assessment methods, they will have the opportunity to influence the institutional technology marketplace. Today's solutions could be much more effective with better guidance from the leadership at colleges and universities.

For example, faculty often find themselves overwhelmed with the volume of new technologies and the ongoing upgrades of existing technologies as they struggle to find time to research how to integrate the technologies into their teaching. Faculty new to online learning will commonly try to replicate their physical classroom online, but this is a classic McLuhanesque mistake.6 Optimizing the use of technology in teaching and learning depends on the ability of the institutional and academic leadership to help faculty develop their digital competency and then to continue to provide learning opportunities to keep their competencies current. Faculty need ongoing digital literacy opportunities that enable them to better understand not only educational technologies but also the social technologies that are affecting their everyday lives and the everyday lives of their students. Those students expect engagement in their instruction. Faculty need to understand instructional narrative and the implications of media as part of their technological introduction. This is more than just training on a particular technology. It is, as the saying goes, the difference between giving a man a fish and teaching him how to fish.

The effective optimization of instructional technology also requires rethinking, reinforcing, and clarifying roles and relationships among faculty, librarians, teaching and learning center professionals, and IT professionals. They all need to view themselves as colleagues and even partners in designing the right infusion of technology resources at the right time during the instructional process.

Is all this a tall order? Yes. But it is directed toward the primary mission of higher education and is thus well worth addressing. If college and university leaders do not optimize the use of technology in teaching and learning, existing and emerging alternatives will almost certainly step forward to fill the gap.

Advice

- Work with academic leadership to articulate the institutional strategy for the use of technology in teaching and learning to best fit the institutional culture and priorities.

- Translate that strategy into a teaching and learning technology roadmap that prioritizes the technologies that will best achieve the institutional strategy and fit institutional resources.

- Define and clarify roles in supporting instructional technology to bring together all relevant institutional parties as productively as possible.

- Move to a technology support model that aligns technology integration support and faculty professional development that is course/program specific and based on research that demonstrates improved student engagement and success.

- Ensure that faculty have sufficient support and release time to integrate the technologies into their courses.

Issue #3: Developing IT Funding Models That Sustain Core Service, Support Innovation, and Facilitate Growth

"When it comes to innovation, is the IT funding principle: 'We optimize new IT investments for the entire institution' or 'We optimize new IT investments for the individual units/departments' or both? Pricing models will emerge accordingly."

—Karin Moyano Camihort, Dean of Online Learning and Academic Initiatives, Holyoke Community College

As governmental financial support for higher education continues to decline, both public and private institutions are desperately trying to focus scarce resources on strategically important needs.

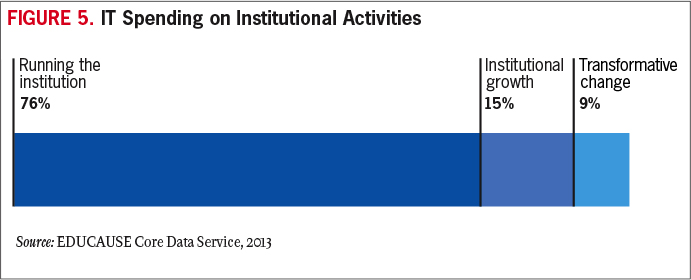

To create funding models that will sustain IT operations, IT leaders need to clarify to institutional leaders and boards of trustees why IT services are strategically important to the enterprise. Articulating and making some of the tough strategic choices explicit is fundamental to developing a sustainable funding model. As the role of information technology in higher education matures and as institutions are increasingly pressed to balance costs with tangible benefits, IT leaders will need to strengthen and leverage their relationships with governance groups, connect execution with strategy, and exploit funding models tied to institutional strategy (see Figure 5).

EDUCAUSE defines governance as "how a higher education institution is organized for the purposes of decision making and resource allocation and how the varying parts are managed in a way that promotes the mission of the institution."7 The distributed nature of higher education institutions, though highly effective in supporting innovation and meeting specialized needs, can be a roadblock to strategic investments and efficiency realization. Institutional IT governance can help achieve and support a clear IT strategy. When IT governance programs have influence over a shared pot of institutional resources and are able to prioritize strategic IT investments, IT leaders can support ongoing innovation and growth across the entire institutional portfolio of functions. In the absence of institutional IT governance, IT projects will be prioritized according to which areas can most easily secure funding for their priorities. Inevitably, worthy and even critical projects will not be funded if they are not sponsored by well-resourced areas.

Capital funding is relatively easy to secure; obtaining additional operational funding is much more difficult. Since most capital projects have an operational impact, the differential access to funding streams can create significant problems for budget managers. To satisfy demand and remain competitive, leaders at higher education institutions have allocated capital funds to cover the development cost of new IT infrastructure, yet they seldom incorporate plans for ongoing operational funding of capital projects. As a consequence, there is a fundamental misunderstanding of the total cost of information technology, and often no culturally accepted billing models exist for one-time and full-life-cycle costs.

To help governance groups understand and support funding for the real cost of information technology, IT leaders need to develop total cost of ownership (TCO) scenarios and vet them with appropriate groups before projects are funded. Higher education information technology is dogged by cost-savings expectations that usually create a false sense of expenditure reduction. In some cases, the benefit of the IT investment derives from risk reduction or new functionality, and cost savings are not to be expected. In other cases, cost savings are theoretically possible but difficult to achieve if non-IT changes, such as business process redesign, are required to realize them. Even if the project is successfully completed, funding may need to shift to derive real institutional savings. For example, an IT project that introduces efficiencies to academic departments or business units may reduce costs for the departments or units and also for the institution overall, but the project may increase IT costs. To realize net savings for the institution, budget funding needs to be withdrawn from the department, and a portion needs to be directed to the IT organization to cover its increased costs, with the balance accruing to the bottom line of the institution. When each department controls its own budget, those shifts and reallocations are very difficult to negotiate and often fall apart, eroding any potential cost savings.

Growth can be managed, but doing so requires service management models that are able to project and prepare for growth. Those models need to include cost management to ensure that service providers understand and budget for both fixed and variable costs. The paying IT customers—whether institutional leaders or individual departments—need to understand IT service cost drivers and how they can help manage those drivers. Funding for growth in variable costs is relatively easy to justify if IT service managers have and can show data on both growth and the associated costs. Funding for growth in fixed costs needs to be justified as well, and that requires data on the cost increases and a justification of the risks that will be reduced, the functionality that will be added or enhanced, or some other compelling reason. This approach also paves the way for discussions of tradeoffs that might accommodate growth without increasing funding, such as service-level reductions, shared services, or outsourcing.

Supporting innovation is a key piece of IT resource justification. Students exist in a digital ecosystem and expect educational institutions to interact with them in the ways that they are used to interacting with each other and with the commercial entities they deal with on a daily basis. Banks, retail stores, and even government services are available to them through a multiplying swarm of devices. Institutional leaders are increasingly aware that higher education needs to deliver services in the same way and that the development of an IT architecture to do so takes resources. To better afford the resources necessary to keep institutions current, the IT organization itself needs to be innovative in the way it is organized, the way it delivers IT services, and the way it works with various institutional constituencies. Recognizing that IT drivers and core services in 2014 may not even remotely resemble those necessary in 2020 demands funding flexibility, since too tight a correlation will act as a disincentive to improvement and will create technology lags greater than those of the last decade.

Different but rigorous strategies for IT core services, growth, and innovation will help in the development of IT funding models that best fit these separate activities and are aligned with the institution and its constituents. Effective IT governance can tie these three activities together and prioritize the IT expense in ways that support existing operations, ensure ongoing innovation, and respond to growth across the entire IT portfolio.

Advice

- Benchmark IT finances by participating in the EDUCAUSE Core Data Service.

- Ensure that IT projects build models for ongoing operational funding into project deliverables and expectations.

- Establish an institutional IT governance structure that is responsible for allocating funding, not just identifying IT priorities.

- Understand the costs and cost drivers of today's IT services.

- Help leadership understand both the costs and the benefits of information technology. Arguments for new IT initiatives should always include cost estimates, as well as estimates of the costs of not innovating.

- Build the costs of growth and maintenance into funding models for core IT services.

Issue #4: Improving Student Outcomes through an Institutional Approach That Strategically Leverages Technology

"Instead of reacting to new technologies, top institutions seek out new technologies as a strategic imperative, leveraging these innovations to improve learning inside and outside the classroom with data decision making, enhanced pedagogy, and better student outcomes."

—Lisa M. Davis, Vice President for Information Services and Chief Information Officer, Georgetown University

The benefits of completing a college education are widely known. They include higher lifetime earnings, greater levels of happiness, increased civic engagement, and reduced health risks. There are also societal benefits as the proportion of college graduates in the population increases. So it is in our own best interests to help both individuals and society by improving the success of students at our higher education institutions.

There are few cases in which technology by itself has helped students succeed. However, there are opportunities for technology to support student success initiatives. The first task for any institution is to assess both the institutional needs and the most current remedies for the pain points that are identified. Although this is a constantly and rapidly evolving area, some specific examples include the following:

- Developing a training course (or workshop) to help students understand the technology landscape of the institution and how they can use those tools to succeed

- Removing barriers—such as access, usability, and lack of support—to the effective use of technology

- Using technology to recast large lecture courses and support pedagogical transformations

- Using technology to provide flexibility for students to match the course with their learning style

- Using technology to distribute learning content in multiple ways, including lectures (live and archived for review), electronic texts, and learning management systems

- Using technology such as peer tutoring, discussion boards, and group videoconferences (e.g., Google hangouts) to facilitate synchronous and asynchronous interactions with others and to promote collaborative learning

- Considering the emerging role of tools used traditionally by business (i.e., CRM) to manage the institution's relationship with the student

- Applying elements of what is being learned in competency-based education initiatives at an institutional level for traditional students

Institutional leaders continue to emphasize, and pour resources into, improving student retention and completion. Technology can be applied to develop the broad area of learning analytics to provide feedback to students on their behavior (both past and predictive), to faculty on the effectiveness of the pedagogy employed in the course, to content providers (and faculty who select the content) on the effectiveness of the content used in the course, and to administrators on broad systemic issues and trends.

Many colleges and universities have student success committees that focus on initiatives to improve course completion, program completion, and student support services. Examples of initiatives can be found in the areas of teaching and learning and student support services. In the area of remedial education, great strides have been made in reducing time to completion for remedial students and in increasing retention and completion rates. An example of the work occurring in the area of student success can be found on the Achieving the Dream Interventions Showcase website, with many of those interventions strategically leveraging technology.

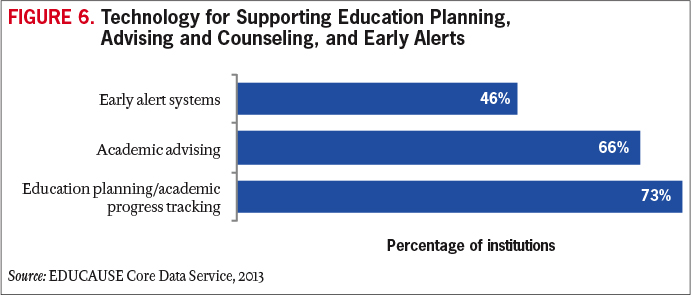

As data analytics tools have become more sophisticated, institutions have been better able to recognize students' challenges and track students' journeys. With the implementation of early alert systems, advisors and faculty have been able to assist students with just-in-time intervention recommendations. In addition, it is becoming commonplace for advisors to have access to data beyond the traditional ERP demographic and student grades—data such as course performance through learning management systems, early alert information, tutoring participation, and education planning information (see Figure 6). Systems like these, sometimes referred to as Integrated Planning and Advising Services (IPAS),8 permit the advisor to support and coach students based on a comprehensive view of the students' information throughout their educational journey. In the area of online education too, wraparound student support services are mirroring the on-ground experience, with some colleges and universities implementing career coaches with supporting technologies to provide services to online students. The integration of technologies in each of these areas has had a positive impact on improving student outcomes.

A variety of existing tools, many still in the early development stages, can help institutions gather data to identify students' success opportunities and their achievements. This information is only as good as the data, however. To find the low-hanging fruit, IT leaders need to begin the data conversations to locate tools that may already be generating useful data. To capture relevant aspects of the student experience, leaders must think institutionally and identify technology resources that can bring together the diverse and enormous data sets that represent this experience.

As was discussed last year, when this was the #1 issue in the 2014 Top 10 list, looking at this data may raise privacy issues, so leaders must remember to include the appropriate individuals in these discussions to ensure compliance, security, and privacy.

Advice

- Keep in mind that students consider success from a holistic view of their campus experience, not necessarily their experience with just a course or a semester. To maximize the impact of technology, identify the combination of data and tools that will encompass as much of the institutional experience as possible.

- Remember that results will be only as good as the data. Take time in the beginning to build a reliable strategic foundation by starting with concise outcome objectives, and then develop the data-driven questions that will ultimately define actionable steps to influence success.

- Work with key individuals from various institutional areas to identify data that may be available at an individual student level and that could be combined with other values to establish an assessment point for the student. Next, consider comparing this assessment point with the student's success level and attempt to identify some trends. Drill down to indicators that can be used as targets for predicting success and for identifying early warning signs.

- Ensure that the project is embedded in a cross-institutional student success effort that includes all relevant parties. Dedicated student success teams or cross-departmental governance structures can be the vehicle for organizing consensus. Don't allow a perception of IT ownership to develop.

- Resolve problems in academic and business processes before implementation; don't adapt applications to dysfunctional processes.

- Define the role of faculty in improving student outcomes through the strategic leveraging of technology.

- Determine how much individualized student data should be shared with advisors in supporting improved student outcomes.

Issue #5: Demonstrating the Business Value of Information Technology and How Technology and the IT Organization Can Help the Institution Achieve Its Goals

"We also add value by creating new ways for those who know us less well to develop affinity with our institutions. A small MOOC my college offered made us known to groups of prospective students who would never have paid a moment's attention to any traditional advertising messages we might have sent. By joining their party first, via our technologies, we put ourselves in a much better position to invite them to our party."

—James Kulich, Vice President and Chief Information Officer, Elmhurst College

IT leaders need to continue to get better at drawing the lines from technology initiatives to their institutions' changing strategic objectives and on to the ultimate bottom lines of mission and means. Successfully demonstrating the business value of information technology to the institution begins with developing a clear understanding of the various ways in which technology as a whole and the IT department as a unit add value to the institution. Institutional leaders' struggle to respond to changing public perceptions of the value of higher education itself is a complicating factor. Herein lies an opportunity for IT professionals not only to demonstrate the value of the IT organization's particular offerings but also to create new and significant value for the institution. This requires thinking of technology strategy as both a consequence and a driver of institutional strategy. IT leaders, who have the ability to see the entire institutional landscape and can offer strategic insights for moving the institution forward, have never been more important to the well-being of colleges and universities.

So, in what ways do IT leaders add value? They add value to the organization by enhancing the core product—namely, the learning experiences of students and the teaching activities of faculty. They add value very directly by creating new channels through which students can access institutional offerings. The channels that online opportunities provide would not exist without the technologies delivered and supported by the IT organization. From a business perspective, this creates new sources of revenue, a critical objective for virtually all colleges and universities. Drawing a clear line that connects specific technology initiatives with tangible revenue for the institution is a powerful way to demonstrate the business value of technology—and of the IT organization.

And of course, the yin of revenue is balanced by the yang of cost reduction. Stories of expense reduction and efficiency are perhaps easier to identify and tell, and they should be carefully and diligently told, but IT leaders must be careful to also emphasize the much larger potential that a clear focus on the revenue side can provide. Doing so can help to avoid the impression that the value of information technology is limited to simple acts of automation and efficiency. Part of this work entails ensuring that the institutional leadership understands what is and is not possible. Many times, the need to have the value discussion in the first place is because leaders are not inherently feeling the value. Those in the IT organization must take the time to develop and provide clear data-based information about the services they deliver and value they provide.

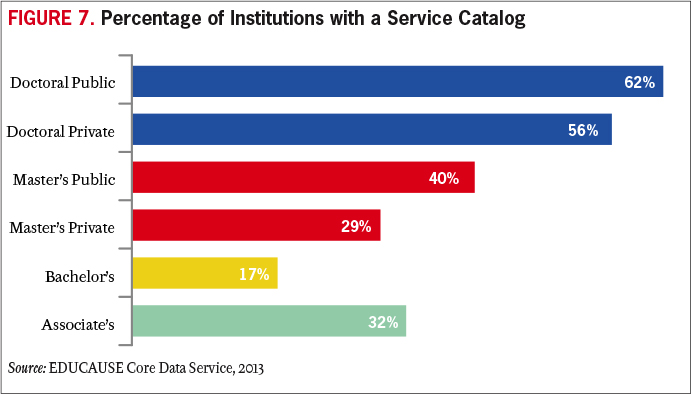

One way to demonstrate value is with well-constructed service portfolios and service catalogs. A service portfolio provides a high-level overview of how funds are spent on major institutional strategic and operational goals and is geared toward institutional leaders. A service catalog (see Figure 7) provides a more detailed view into how IT dollars are spent on IT projects, products, and services and is geared toward IT leaders. Combined, the service portfolio and the service catalog can be a useful tool for showing the business value of the investments that institutions make in information technology.

Assembling a service portfolio and catalog may be the IT organization's first comprehensive view into the actual value it is bringing to the institution. Depending on that value, IT leaders may first need to focus on quick fixes to better align their services with the institutional mission. Before IT leaders can advocate how information technology can be leveraged to drive the business, the IT organization must be operationally effective and efficient. Institutional and business unit leaders must view the IT organization as providing operational excellence and outstanding customer service before they will consider it as a partner in delivering business value.

The CIO and IT leadership teams should remember that they are the primary marketing avenue for sharing the value that information technology brings to the institutional mission. IT leaders spend about 10 percent of their time on governance and planning and on innovation with business and academic units.9 IT leaders thus must be intentional about identifying opportunities for communicating how the IT organization is helping the institution. CIOs must establish strong and trusting relationships with their peer business leaders.

Sharing the value of information technology begins with IT leadership but must extend to the entire IT organization. All IT staff must understand how their work contributes to the institutional missions and priorities. They need to understand the IT organization's capabilities and priorities and how the organization can advance the institution, the individual business units, and the faculty, students, and staff with whom they work. IT leaders can encourage and enable IT staff to learn the mission, business processes, and requirements of business units in order to understand how information technology can best be leveraged. Getting to this point may require a culture change within the IT organization. At the very least, all IT staff should know both the institutional and the IT priorities to ensure that everyone is telling the same story.

Advice

- Map IT priorities to institutional priorities. Find the points of intersection with the business unit, operations, customers, and technology. Partner with the business unit to develop a roadmap and to align the business with the IT architecture.

- Don't wait for an invitation to discuss business and customer impact. But don't try to boil the ocean: keep focused and be clear about what the IT organization can and cannot do. IT leaders must be translators, using terminology that resonates with non-IT experts and connecting the dots between the technology capabilities and the business needs. Develop a small set of short and simple stories about concrete ways in which technology has improved the learning experience at the institution, created access to institutional resources, strengthened affinity for the institution, generated revenue, and streamlined operations. Focus at least as much on helping others see what is possible with technology as on showing how technology investments improve current institutional life.

- Develop a service catalog to serve as a base for connecting the work of the IT organization to the larger institutional strategic objectives.

- Implement a metrics program that can demonstrate the extent to which the IT organization is achieving its service-level goals, customer-satisfaction goals, and financial goals and is delivering on strategic priorities.

- Ensure that IT leaders and IT staff understand what drives academic and business value for the institution and can identify and articulate how technology can deliver that value. Consider attending non-technology conferences to learn how business officers, faculty, and academic leaders think about technology and what their pressing problems are. Be the translator for business strategy.

- To reach the broader institutional community, consider newsletters, brown-bag gatherings, and roundtable discussions and take advantage of recurring events such as National Cyber Security Awareness Month and start-of-the-semester gatherings.

Issue #6: Increasing the IT Organization's Capacity for Managing Change, Despite Differing Community Needs, Priorities, and Abilities

"Technology is now integrated into just about every aspect of our colleges and universities. That allows us a myriad of opportunities to use technology to help students succeed academically. Using technology to help students succeed is at the core of what we do."

—Steve Fleagle, Chief Information Officer and Associate Vice President, The University of Iowa

Change is the watchword today and going forward. In the 2011 book Race against the Machine, MIT economists Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee write: "Advances like the Google autonomous car, Watson the Jeopardy! champion supercomputer, and high-quality instantaneous machine translation, then, can be seen as the first examples of the kinds of digital innovations we'll see as we move . . . into the phase where exponential growth yields jaw-dropping results."10 When technology changes, organizations are always challenged to adapt to new circumstances. This is particularly true of the organizations tasked with implementing and maintaining the technology itself.

The higher education community is struggling not only with the pace of change in information technology but also with the variety and sheer volume of change. Information technology is increasingly important to and increasingly integrated with all aspects of both the strategic and the operational functions of the campus. The challenge is how to engage multiple areas of the institution and expand services in numerous simultaneous initiatives. Meanwhile, institutional information technology is reengineering its infrastructure, platforms, and services. Those change efforts are often additive to the applications being introduced as part of new business-area initiatives.

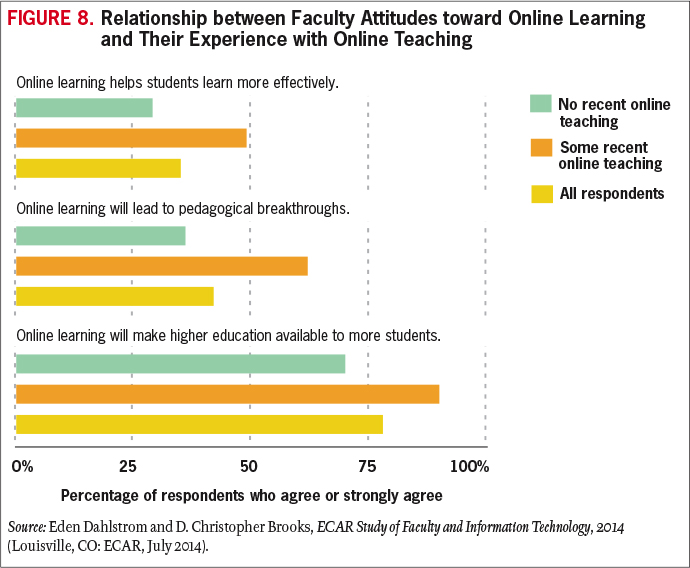

Ideally, the institutional stance toward change is proactive, and IT leaders have the vision and good sense to advocate, to broker, and to prepare their various constituents for upcoming changes while sustaining ongoing operations. In reality, end users vary widely in their predisposition to technology. As a group, students and faculty are positively disposed toward information technology, but as individuals, they run the gamut (see Figure 8). And attitudes influence behavior: the way faculty and students adopt and use technology tends to reflect their attitudes.11

The IT organization's history of execution can influence community openness toward future technology changes. The shadow cast by a deeply flawed ERP implementation, for example, can last a decade or longer.

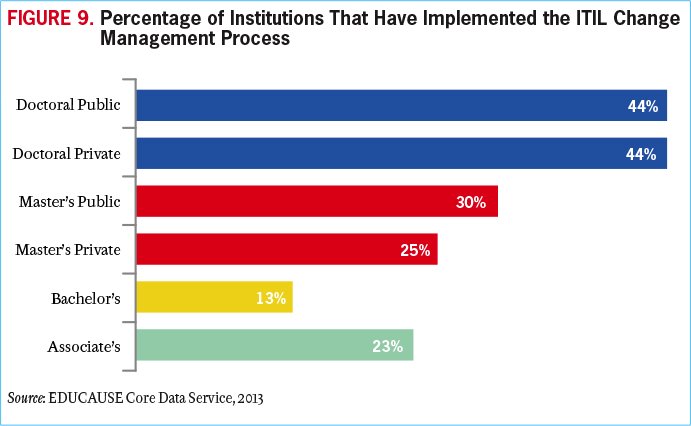

Change management is precisely that: managing change rather than letting change happen on its own (see Figure 9). Successful change management is not accidental or organic. It is intentional and has multiple components. Many institutions adopt a specific approach to implementing change—approaches such as ADKAR, Kurt Lewin's change management model, and John Kotter's eight steps.12 Regardless of the model, managing change requires a strategy in which the goals and focus of the change are clear to internal and external constituents. For example, the corporate consultant Glenn Llopis advises being able to identify what the successful implementation of a change strategy would look like, knowing what the change strategy is trying to solve, and identifying the required resources and relationships to implement the change management strategy.13 As the IT organization sifts through the different needs, abilities, and priorities of the institution and tries to adapt to change, it must avoid being caught in a vicious circle of tactics with no purpose.

A good change management strategy has multiple components, which include communications and inclusiveness. John Jones, DeAnne Aguirre, and Matthew Calderone provide ten sensible principles for managing change by keeping the human element at the center.14 Involving every level of an organization, creating ownership, assessing the cultural landscape, and communicating effectively are key factors. Change always affects somebody, somewhere—both internally and externally. IT organizations must do everything possible to find engaged people who can advocate on behalf of the change strategy. It helps to have champions at all levels: executives who can demonstrate the institutional leaders' commitment, area leaders who can reinforce commitment with their workforce and explain how the change will benefit their part of the institution, and individual influencers who can help determine success factors, identify and address pain points, and evangelize with their colleagues.

But change management involves more than communications and inclusiveness. A successful change is a fully designed change. Too often, institutional leaders conflate new initiatives with new systems and fail to fully think through and execute on the business-end components. The successful introduction of a new system might require new or reengineered business processes, new roles, and even different organizational structures. Every change also demands a good support strategy. Rollouts are viewed as smooth when end users are already familiar with the new system, when they have job aids, training, and other practical tools, and when they know where to go for help and receive it promptly and effectively. Changes affect the IT organization as well as business units. A change management plan needs to include both sets of changes. The multiple components of change are substantial and need to be built into project plans, timelines, and budgets.

Change management is challenging on a good day. As technology changes increase in pace, variety, and volume, change management challenges multiply. Change management needs to be become a core capability of the IT organization and a core competency of the institution overall.

Advice

- Create a change management role to ensure that someone is expert in and able to lead and support change management efforts.

- Adopt a change management methodology and use it to develop a change management process and toolkit to support change management efforts.

- Review IT policies to see whether they support change while protecting the legitimate interests of privacy and security.

- Have separate but linked innovation and operations activities and budgets to unleash the innovation work without burdening the operations work.

Issue #7: Providing User Support in the New Normal—Mobile, Online Education, Cloud, and BYOD Environments

"The explosion of online education, of course, also increases the demand for 24/7 support—support that may be difficult or impossible for resource-limited IT departments to provide."

—Jenny Crisp, QEP Director and Assistant Professor of English, Dalton State College

Providing IT support has always been challenging. Faculty, staff, and students with myriad needs have different requirements of technology, different levels of expertise, different communication styles, and different service expectations. Technical issues can be sporadic and seem often to appear only when the IT support person is not present to identify them. Root-cause analysis within a complex infrastructure can sometimes devolve to trial and error. And users want their problems solved now, now, now.

The "new normal" of mobile, online learning, bring-your-own-everything, and cloud computing is the latest step in the gradual migration of institutional systems from a tightly controlled environment to a very diverse environment that is out of the direct control of the institution. Ten years ago, most college and university systems were hosted on institutionally owned servers and were delivered across institutionally owned networks onto institutionally owned computers. This computing environment was relatively homogeneous, and the support responsibilities were clear. Supporting Macintosh PCs or multiple versions of Windows operating systems was among the major challenges of the day. PDAs were niche devices, and phones still weren't very smart. How easy that seems in retrospect.

Today, faculty, staff, and students expect to use institutional systems and to access, transmit, and store data anytime and anywhere using a wide variety of personal and work devices and applications. Institutional applications have burgeoned, and integration points have increased exponentially. The complexity of IT support has increased accordingly.

Because faculty, staff, and students already use mobile technology in their personal lives, they're likely more proficient with it than they would be if forced to use a single platform for work. Unfortunately, this variety that helps enable and free faculty, students, and staff also means that IT support staff must become proficient with a much wider variety of platforms and systems. The "new normal" also presents new opportunities and new challenges. In a BYOD environment, end users may be more skilled with their devices than previously. At the same time, however, IT professionals must become more skilled with a wide variety of technologies and platforms.

The rising popularity of cloud computing raises issues not just for providing support for a wide variety of platforms but also for ensuring data security. Even institutions that arrange for secure cloud computing for institutional services have to consider the risk that end users will choose to use alternative cloud computing services. Another challenge of cloud computing is when IT support staff find that their ability to troubleshoot and diagnose user problems is curtailed because their access to cloud-based infrastructure, platforms, and services is more limited than their access to campus-based technologies.

In many ways, issues surrounding user support do not change in the new normal. Many of the challenges remain the same. Fortunately, many of the best practices in IT support also apply and can be more useful than ever.

It is very important for the IT organization to clearly define the amount of support that faculty, staff, and students can expect. Service level agreements (SLAs) exist to provide clear information about what the IT organization can support—as well as when, where, and how quickly—and about end users' responsibilities. SLAs define the limits of support. They also commit the IT organization to a certain base level of service and describe the metrics that the IT organization will use to measure its ability to achieve that baseline. The best SLAs are a negotiation between the IT organization and the business units, ensuring that the IT support end users need is within the bounds of what the IT organization is actually capable of delivering with its current funding levels.

SLAs should be regularly renegotiated. In the new normal, this provides the IT organization an opportunity to understand current support needs and to negotiate either new concrete limits or funding increases to support increased demand. IT organizations have commonly set priorities for IT support to clarify which applications, devices, and environments will receive full support, best-effort support, or no support. It can be just as important for the organization to document and communicate the configurations and combinations that don't work with institutional resources or that constitute special security risks.

Effective, repeatable processes can help IT support become more efficient. To date, the focus has been on ITIL processes such as incident management and request management. These are still excellent paths to efficient IT support. With these service management processes in place, IT organizations can consider moving beyond managing the support transaction to managing the customer. Customer relationship management (CRM) applications in higher education are most commonly applied to student applicants or alumni. Using a CRM to support the institutional community can help IT support move from a problem-oriented service to a value-oriented service.

Escalation paths have always enabled IT support staff to easily and quickly determine who, where, and how to escalate support issues. Now escalation paths will increasingly leave the institution. Tracking support tickets can become particularly challenging.

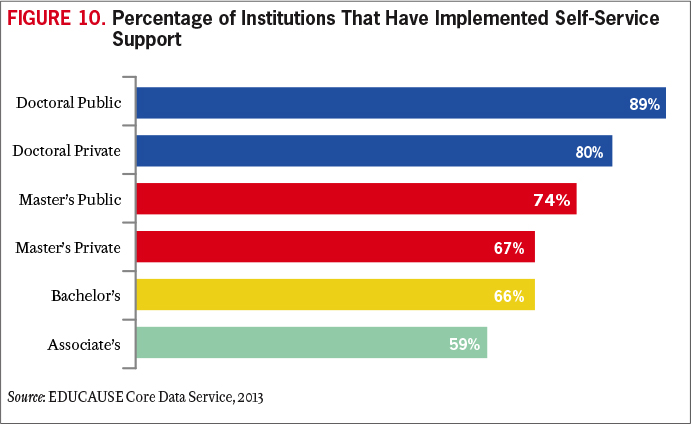

Knowledge management is key. Providing support in the new normal is an incentive for institutions to invest in or expand knowledge bases or self-support portals. Self-service support is the least-expensive form of IT support and can also provide better support 24/7; solutions that are documented; and a consistent, searchable database (see Figure 10). Self-service support documentation provided by the IT organization can be augmented with moderated community solutions to extend the efficiency and expertise of the IT support professionals.

IT professionals who can communicate clearly and personably with end users are still the most valuable resources an IT staff can have. A certain level of empathy is useful, not only for increasing user satisfaction but also for being able to address questions well. The ability to put oneself in the place of an end user who does not spend all of his/her time steeped in the details of technology is a valuable skill, and one that should be fostered whenever possible.

Advice

- Help designers and faculty ensure accessibility and ADA compliance in online education.

- Develop a data security governance/storage policy so that end users know which data is appropriate for mobile and cloud services.

- If mobile support is currently at a "best effort" level, consider making at least some aspects of it "mission critical."

- Consider a mobile device management (MDM) solution for mobile devices that access institutional data.

- Audit the management of IT support to determine whether such practices as SLAs, ITIL processes, and a service catalog are in place.

- Invest in knowledge management. Begin with a knowledge management tool for IT support staff. Then expand the capability to provide end users with self-support resources, extending to self-provisioning if possible.

Issue #8: Developing Mobile, Cloud, and Digital Security Policies That Work for Most of the Institutional Community

"Those of us whose job it is to think about these things understand the issues and technologies and with some thought (and some long conversations with college counsel and risk management personnel) can come up with a strategy for addressing the situation. Developing policy language that will explain the problem and the strategy for dealing with it in ways that are understandable to the bulk of the college community is infinitely more difficult."

—Mark I. Berman, Chief Information Officer, Siena College

Historically, higher education institutions have been in full control of both the computers and the services storing college/university data. We now find ourselves in a world where faculty, students, and staff access campus data with a wide variety of devices and services—many of which are outside the control of the institution. The proliferation of mobile devices and the use of cloud services create new questions for IT policy makers about information security and data management. Employees and students alike are using personally owned mobile devices to access institutional resources. E-mail is the most obvious, but with shared institutional data residing in the cloud through services such as Microsoft Office 365 and Google Apps for Education, people are accessing data in the form of spreadsheets and reports from a variety of mobile devices from different vendors, most of whom offer to back up data from the mobile device into their own cloud-based storage. With this confusion of services and profusion of providers (most of whom the institution has not contracted with for protecting the data), managing institutional data becomes more and more difficult.

The risks of doing nothing are clear. When institutional data can easily, and accidentally, migrate outside of the control of the institution, it becomes critical for the IT organization to develop clear information and data-governance policies that define and spell out the appropriate ways to store and access campus data.

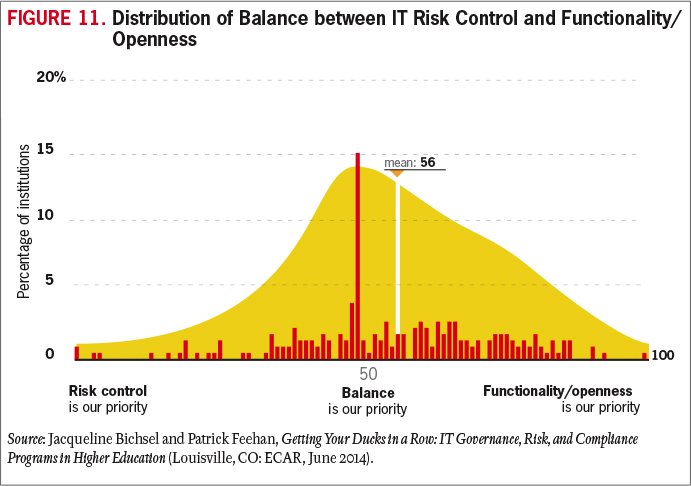

The dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of technology and its use can prove challenging for institutions whose security policies and procedures may be geared for traditional information systems. At most institutions, students and faculty are free to explore and use emerging technologies (in some cases, even to create them). Information security policies must address both this need for exploration and the risk appetite of the institution (see Figure 11).

The specific cases of mobile devices and cloud computing can be addressed under a general framework for adapting policies and processes to focus on protecting data, rather than for making changes in technology. Information security policies and standards establish a base threshold for risk tolerance as well as parameters that surround accepted risk (risk mitigation and containment). A well-crafted information security policy is focused on broad responsibilities that don't change with new technologies.

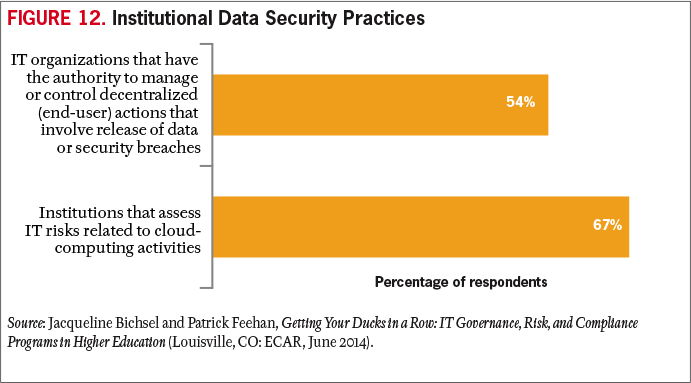

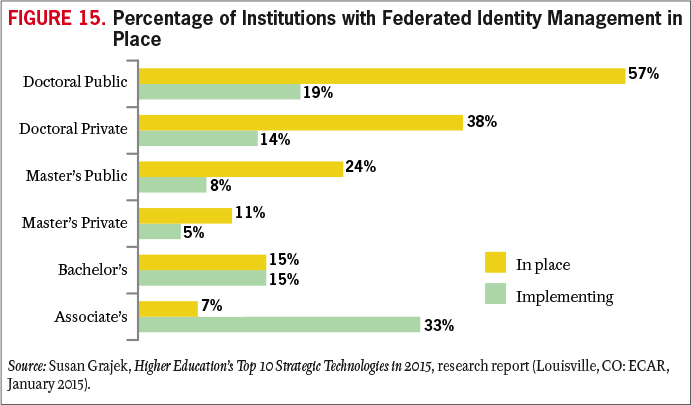

Increasingly, policies have moved away from technologies, users, or networks and have become focused on information (and data governance). This approach provides an opportunity to create risk- and security-focused controls that are largely unaffected by changing technologies. In this manner, mobile and cloud policies can dovetail with data-governance efforts (see Figure 12). Data governance as a framework addresses key issues of information (e.g., availability, integrity, security, and privacy) regardless of the location and technology.

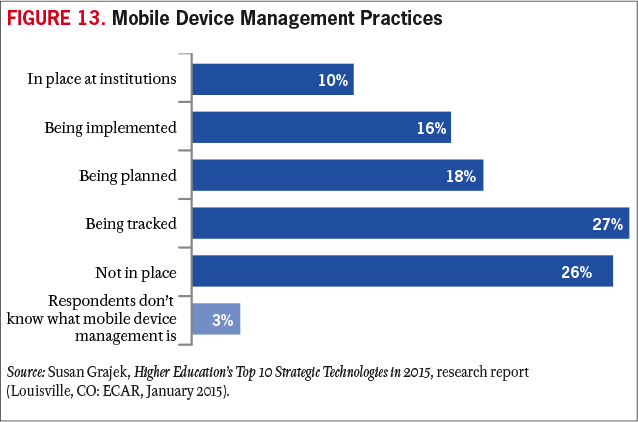

Because data security requires the cooperation of every person who comes in contact with institutional data, the mere existence of policies is not enough. One thing that can help is a well-developed information security awareness and training program. Goals would be to incorporate the program into the new employee onboarding process and, ultimately, to make its completion required of all members of the institutional community (students, faculty, staff, and other affiliates). Even with those goals, institutions will need to find ways to enforce policy, at least for institutionally owned devices. Technology-based solutions like mobile device management (MDM) software are becoming more common (see Figure 13). Still, that addresses only a small fraction of all the devices that are being used to access sensitive data, meaning that policy and awareness remain our most important tools.

Advice

- Clarify the institutional approach to emerging security issues to determine when the institution should try to "get ahead" of emerging issues or when it should "wait and see" how the issues affect peer institutions.

- Strengthen ties to the higher education information security community by participating in the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC) and the Research and Education Networking Information Sharing and Analysis Center (REN-ISAC).

- Review the overall institutional approach to creating policies to ensure that they are sufficiently broad and technology-agnostic to accommodate changes in new technologies.

- Decide which policies should address all constituents in the same manner and which should be adapted to various groups such as students, faculty, staff, and affiliates.

- Ensure that information-focused policies like data governance are technology-independent. However, regularly track changes in the technology landscape to review potential implications for and impact on policy.

- Ensure that mobile and cloud policies are enforceable.

- Develop a communications and enforcement plan to ensure that members of the institutional community understand and adhere to policies.

Issue #9: Developing an Enterprise IT Architecture That Can Respond to Changing Conditions and New Opportunities

"Taking time to plan ahead with new procurements will provide you a keystone for future success."

—Mark C. Adams, Vice President for Information Technology, Sam Houston State University

How higher education will respond to the acceleration of change remains a top issue for 2015. Using agility as a watchword, IT professionals have often tried to predict or respond to change by emulating a successful effort at another institution. Yet the velocity of change in 2015 and beyond skews past formulaic response. Agility now requires institutions to learn, grow, respond, and become self-sustaining in shorter amounts of time.

Enterprise IT architecture is the overall structure within which the institution's information technology functions and interrelates. An effective enterprise IT architecture is intentional and scalable, ensuring that IT systems, services, and data flows can work together and are designed to support business processes and to advance business strategy. As technology environments and options continue to expand, they present new opportunities to provide value to higher education. Without a clear IT architecture as an anchoring reference, those new opportunities can easily burden an institution with a marvelous set of point solutions that interoperate only with great initial and ongoing effort (and expense and risk).

For many IT professionals, the appeal of working in academia is the opportunity for new learning experiences through the rich interplay of academic communities, technology, research, and collaboration. However, budget constraints and conflicting priorities within higher education subcultures have often challenged the feasibility of an IT architecture that truly works for the entire institution. The "enterprise" in enterprise IT architectures refers to a set of IT solutions that serve the entire institution. The most effective IT architecture is one that works for the whole enterprise, rather than being a glove-fit for several individual areas.

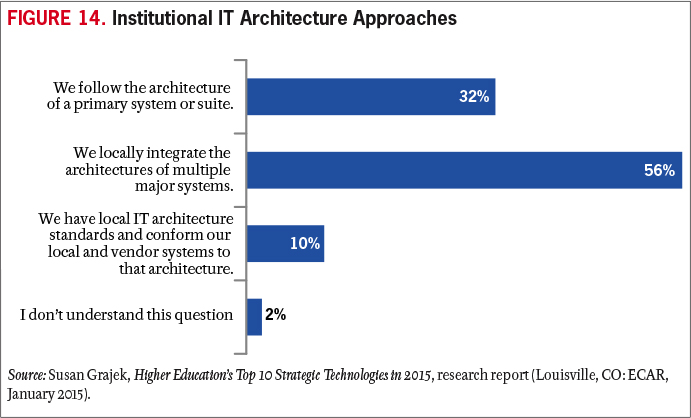

Emerging and maturing technologies are presenting new conditions that enterprise IT architects should consider. They include mobile, multiple layers of cloud solutions, BYOD, increasing digitization of the higher education missions, and the Internet of everything. All these trends generate data streams and sources that higher education is just beginning to value and use to advance institutional strategy. An effective enterprise IT architecture that can put all the pieces together cost-effectively and in service to the enterprise can truly become a competitive advantage for institutions (see Figure 14).

For example, as cloud and SaaS applications proliferate through campuses, the integration of those applications into the enterprise IT architecture becomes a major concern and a major risk. Applications that are not integrated into the overarching IT architecture cannot contribute their data to the "Big Picture." They become islands of data that may be useful to the individual department but can create a blind spot in the top-level view of the institution.

The creation, or development, of an IT architecture that can easily adapt and absorb this quickly growing collection of independent software services is critically important to maintaining a comprehensive picture of the enterprise. We have all heard the term big data and understand that big rewards can be reaped from the collation and analysis of all the small pieces of information collected throughout our organizations. An IT architecture that can easily incorporate new applications is going to be better able to present a clear picture of what is going on and better able to inform strategic decision making.

Centralizing and standardizing further simplifies the ability to respond quickly to changes. If a single platform is used in multiple instances, often a change can be made once and then quickly duplicated to similar resources. Centralized approaches for services minimize instances that would need to be changed, so that when needed, a single change can provide enterprise impact.

Good enterprise IT architecture can make the IT organization and the institution more effective. The obverse is also true. A recent Gartner warning applies to more than just applications. In the absence of an architecture, "applications are built with little regard for structure, fitness for purpose or maintainability. And, a lack of investment in application architecture seriously compromises the ability to develop composite applications and business process management solutions—both of which rely on the ability to readily integrate heterogeneous applications and data sources. Finally, an old or accidental application architecture results in systems that are difficult to change and difficult to debug, driving up costs, budget risk and schedule uncertainty."15

A well-defined enterprise IT architecture will be instrumental for managing change and optimizing opportunities. To sustain and grow a dynamic IT architecture, IT leaders must not overlook the importance of the IT organizational culture. Great ideas or future roadblocks will arise from the daily decisions of IT staff. Leaders should educate and encourage staff to consider flexibility and adaptability in daily decision making. Additionally the IT culture should adhere to a philosophy of collaboration with institutional partners. A culture of collaboration will facilitate the gathering of more reliable scope definitions for new projects, ultimately simplifying the change process.

Advice

- Determine the extent to which the institutional culture will support a standardized environment and enterprise-wide architecture. Take a strategic and staged approach to implementing enterprise architecture rather than trying to accommodate the entire institution at once. Work with receptive institutional partners to develop a change management strategy to accelerate effective adoption.

- Remember that a dynamic enterprise architecture requires high-level, continuous planning and review. Within the IT organization, establish staff roles that are responsible for enterprise architecture.

- Consider applying agile methodology concepts to culture and operations, as well as to development, to help the IT organization respond nimbly and quickly to changes.

- Whenever possible, select and/or design systems as configurable rather than as fixed single-use resources.

- Develop standards for classifying data in a systematic and consistent manner across all institutional and departmental systems, including those in the cloud.

Issue #10: Balancing Agility, Openness, and Security

"Having the infrastructure and technologies is manageable to a great degree. The human element is perhaps the biggest challenge in this equation."

—Francisca Yonekura, Associate Department Head, Center for Distributed Learning, University of Central Florida

The delicate act of balancing the complex needs for openness and freedom in higher education against the backdrop of an estimated 822 million records breached worldwide remains a forefront issue.16 In a world of increasing and complex security threats, higher education institutions must move from a reactive to a proactive response in their IT security infrastructure. Protecting data and networks while maintaining openness and agility requires a balanced and open approach. The challenges abound.

Perhaps the biggest of these challenges is the human element. Faculty, students, and staff should be prepared and empowered to conduct themselves safely, securely, and ethically in the cyberworld. Tools and programs such as the HEISC Information Security Guide and the Stay Safe Online program of the National Cyber Security Alliance can prove very useful in helping to meet this need.17 To balance agility, openness, and security, IT leaders must increasingly push auditable accountability out to users and their managers.

In addition, as the interest in analytics continues to grow, daily operations throughout the academy are becoming highly dependent on access to data. This is a paradoxical and important issue for higher education in 2015: as the penalties and costs of data breaches grow, the value of the data to be used and leveraged in the academic mission is also growing. Student outcomes are increasingly tied to the brand of an institution as prospective students and their parents try to search for value metrics to help select a college or university. Metrics of real value entail an increased use of available data—and that portends risk. IT organizations must have a strategy to allow access to adequate, secure, and appropriate data for more entities in the higher education ecosystem, while also taking the utmost care for the privacy of individuals.