PLUS: More Exclusive Photos of DiCaprio Here >>

Published in the May 2013 issue.

Guy sitting in a room, talking about how comfortable he feels. Then he cracks his neck.

Thing is, he cracks his neck at the exact moment he's talking about how comfortable he feels — as he's giving a little speech about his feelings of comfort.

This is what he says:

"Most recently, the last few years, I feel way more comfortable than I've ever felt. You always talk about that, and then one day you're like: If they don't like this, well, fuck 'em. What can you do? It's a resignation to life and who you are. Hey, look, I'm pretty well-formed as an adult now. I don't have to impress anybody. You ask yourself these different questions: What do I want to do? Interesting question: What do I want to do? What makes me really happy? I've learned all these things that I'm supposed to do. I know I'm supposed to be in that place and do that thing… but to really, deeply ask yourself that question — What do I want to do?"

First crack comes at the beginning of the speech, as the punctuation of the first sentence.

And it's really loud.

He's sitting in a chair when he does it, in the big empty conference room of a big expensive hotel. He's been sitting in the chair a couple hours. He's been all twisty, one leg slung over the other, the collar of his V-neck T-shirt not lining up with the collar of the blue-and-black-checked shirt he wears over it. He's one of those guys who has to invest a lot of energy into staying put, and so as he makes his speech, he's also untangling himself, putting his hands on his knees and his feet on the floor. And then he starts straining against himself, like Samson in chains. This is how it goes:

When he says "Most recently, the last few years, I feel way more comfortable than I've ever felt," he turns his chin toward his right shoulder, a full 45 degrees. A stripe of blue vein shows up in his surprisingly thick neck.

Crack.

And when he says "Interesting question: What do I want to do?" he turns his chin toward his left shoulder.

Crack.

Each crack has a snappy percussive element, like a fingernail flicked hard against a snare drum. Each one is loud enough to be heard on a tape recorder.

Now, the guy is an actor, so imagine if he cracked his neck like that in a movie while giving a speech about, you know, happiness. Imagine that he's sitting in a big empty room, and he's dwarfed by both its size and its ratty, faded elegance — the scarred little table next to his chair, the yellowed carpet under his feet, the dust-gray chandelier that hangs over his head. And imagine one more thing — that he's wearing a jaunty little driving cap and smoking a battery-powered cigarette with a glowing green tip … no, that he's been blowing smoke rings with the battery-powered cigarette, even though the whole point of the battery-powered cigarette is that there's no fire and nothing ever really burns.

The cracked neck would mean something, right?

In a movie, it would be a gesture — a tell. It would reveal character. If the screenwriter put it in the script, it would serve the story. If the director suggested it, it would serve his vision. And if the actor just, like, did it in a take, it would show how intuitive he is. He would crack his neck to add tension to the scene, to communicate menace, or, at the very least, to undercut his own claims of comfort. One thing is certain: No actor cracks his neck like that in a movie for no reason at all.

But here's the thing:

Leonardo DiCaprio is not in a movie. He's just being himself. The cracked neck is just a cracked neck, not a significant gesture but rather a neutral and therefore inscrutable one. You're not even supposed to ask about it, and when you do the conversation immediately sounds ridiculous:

"You just cracked your neck."

"I did."

"That was some crack."

"It was. It was pretty loud."

And so the cracked neck becomes the measure of the difference between the two lives that Leonardo DiCaprio has made for himself:

In the dark of the movie theater, it would mean everything.

In the light of day, it means nothing at all.

Guy walks into the venerable Hollywood establishment Dan Tana's. Different guy — not Leonardo DiCaprio. But this guy, Rick Yorn, has something very valuable in a place like Dan Tana's back in 1999 — he has Leonardo DiCaprio, whom he has represented as a client since DiCaprio was a kid. When the kid was just a teenager, he made two movies that announced his talent to a new generation of moviegoers the way, says one of his friends, that The Graduate and Midnight Cowboy announced not just the arrival of an actor named Dustin Hoffman but also a whole new style of acting. The movies were This Boy's Life and What's Eating Gilbert Grape, and in the first one the kid stands up to Robert De Niro, in the second to Johnny Depp. And then he made Romeo + Juliet and Titanic, which made him, as a very young man, the biggest movie star in the world. So when Yorn goes to Dan Tana's to meet some friends, he gets summoned to the table of a tanned old man in big black eyeglasses, Lew Wasserman.

Wasserman is the wise old owl of Hollywood, in the sense that he has night vision and talons. He's a combination rabbi and mobster, pope and Caesar, Darryl Zanuck and Henry Ford — he invented the industry he lords over. And now he wants to speak to Yorn about his client.

"Lew was old and near the end by this time," Yorn says. "He died a year or two later. But he knew I was Leo's manager, and he wanted to give me some advice. He said, 'Only let them see him in a dark room.' It took me a minute to figure it out. But what he meant was only let people see him in the movie theater. That's the dark room."

It's harder now, Yorn says. It's harder to live out of the public eye than it was in Wasserman's day. Every citizen has a camera, and every tabloid photographer has a camera with a telephoto lens. The kid lives in a celebrity surveillance state. Still, he's done a pretty good job of "maintaining his mystique," Yorn says — of making his living in the dark. And besides, he's not a kid anymore. These days, when you call Rick Yorn and tell him you want to talk about Leonardo DiCaprio, this is what he exclaims:

"The king!"

He's been a pretty good king, as kings go.

No, we don't know very much about him outside the dark room, by his own design. What we do know is that he's been doing what he's doing for a very long time, and that he seems to have created for himself a life of unalloyed advantage. He has meaningful work and meaningful friendships. He has the power to make any movie he wants and a choice of both directors and women. He can go anywhere he pleases and has lately chosen to go where he feels he can do the most good. He's not only talented but driven. He's dogged in everything he's ever done, a largely unschooled man who's learned the value of doing his homework. If, at times, talking to him about life is like talking about food with someone who's never done anything but order from a menu — well, the menu has been both expensive and extensive, and he's learned enough to know exactly what he likes. He is always in ferocious demand, and yet he has always been in equally ferocious control of his own life, from the time he was very young. Is there anything else we can possibly ask of him, other than to lose control of his life, for our benefit? Is there anything else we can possibly ask of any of them, be they Leonardo DiCaprio or Brad Pitt or Matt Damon? We have a prejudice about kids who become kings, in that we like to see them earn their crown, preferably by enduring some kind of trial — by going off to battle or taking speech lessons or marrying a tragic queen. But what can we possibly ask Leonardo DiCaprio to endure, to prove himself to us? Can we see him as any less a man because he made the road to manhood look so easy?

A few years ago, he was on a plane. He was flying to Russia. He was due to meet with Vladimir Putin at a conference Putin organized to help save the Siberian tiger. He's taken the tiger as his cause. He was on a Delta flight to Moscow. He often flies commercial, according to friends who say that, after all, he's just a regular guy. The flight had departed Kennedy and was already out over the ocean. He was looking out the window when he saw one of the engines explode.

Remember that scene in Twilight Zone: The Movie when the guy looking out the window sees the monster gleefully tearing apart the wing? Leo fucking loves that movie, loves The Twilight Zone. He's trying to produce a Twilight Zone movie of his own. But it was like that — he was, like, the first to see the engine explode, so he didn't know if the engine had really exploded. Like a lot of famous people, he's learned how to sleep on planes, so he thought maybe he was dreaming. Or crazy, like the John Lithgow character in the movie. He thought to himself, Holy shit! but he didn't want to come right out and say that. Then some guy in the first-class cabin said "Holy shit!" really loud, in a heavy Russian accent. Then the lights went out. Then the other engine, the second engine, went out. He's on this plane out over the ocean, the lights are out, and the silence is, like, consummate. Sure, there are people screaming and shrieking and crying and praying, but the silence is what undergirds everything, the silence is what's inspiring people to make all that noise. The plane's gliding, dude. The pilots had to shut down the working engine to make sure that the engine he saw explode wasn't on fire.

He had been in a similar situation once before, when he was tandem skydiving and the chute didn't open. He was just falling, falling, falling, in that eerie encompassing silence of unbroken descent... while his instructor worked to cut the line and deploy what turned out to be a second tangled chute. So he recognizes this feeling. He's felt it before. He says to himself, This is not good, whereupon he hears the Russian guy echoing him in that heavy Russian accent, This is not good... .

Then the second engine restarts, and they go up... but now they have to fly around for an hour, dumping fuel into the ocean, because otherwise they'd be too heavy even for the emergency landing, the descent into the swirling red lights assembled on the tarmac. He can see them, too, through the window in the distance, the consoling fire instead of the annihilating one, getting closer and closer — and then they land, and he signs autographs for the crew.

And then he has to figure out what to do next. He has to decide whether to get in the air again. It's not like he wants to, because when you fall like that, you realize something about the air — it's air. It's not solid, and it can drown you. But he has — and this is what people don't realize — responsibilities. So he finds a private plane willing to go right to St. Petersburg. By now, though, there's weather over the Atlantic, and the private jet takes such a beating that it can't reach Russia on the allotted fuel. There's an unscheduled landing in Helsinki. Still, he makes it to St. Petersburg, makes Putin's conference, and he writes a check for the tigers — $1 million of his own money. And Putin recognizes not only a man who loves tigers as much as he does, he recognizes a peer. One is a politician who has acquired enough power to live like a film star. One is a film star who has acquired enough fame to live like a politician. They're both the same; they both exist in the world of transcendent and transnational celebrity, and so when Putin addresses the conference, he asks Leonardo DiCaprio to stand up. He recounts the whole story. And then at last, speaking in Russian, he pronounces DiCaprio a "nastoyashi muzhik":

A real man.

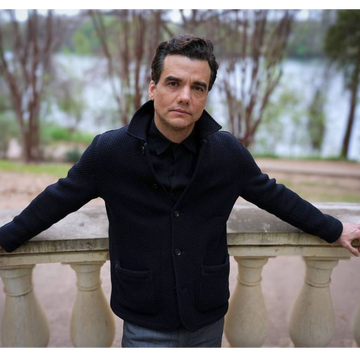

He does not yet look like a real man. Not with that face. It's a famous face — famous for looking young. He's thirty-eight years old, but he doesn't look substantially different than he did sixteen years ago, when he went from promising film star to international pop star, and his fame jumped the boundaries of Lew Wasserman's dark room. He had the kind of young man's face beloved by young girls, soft and smooth, maybe even a little safe: a beautiful face, not unlike their own. And he still does, even now, in the haggard hotel room that scrubs even a mug like DiCaprio's of its dark-room mysteries.

In person, he has what he has in the movies — unsullied cheeks, eyes striking not just for their color but for the volatility of their regard, and a big mobile forehead that he forces into frowns both expressive and utterly evanescent. It's an American face, wide and malleable, with the nibs of a mustache and beard, and dark exotic eyebrows that function like Gothic arches in a megachurch. Eight years ago, his face was attacked by a woman with a wineglass at a party in the Hollywood Hills. He sustained seventeen stitches. But those scars have been either meticulously or miraculously dissolved.

It is no longer an unmixed blessing, that face. His manager, Rick Yorn, calls him "a character actor in a leading man's body," and he has reached the point where his face needs to grow into his roles, not vice versa. His last two movies have seen him take on his own beauty — with makeup and claustrophobic prosthetics in Clint Eastwood's J. Edgar, and with what he calls the "old-fashioned sand paint" that stained his teeth in Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained. His friends suggest that he's eager to leave his boyishness behind, but until he finds a replacement for it he'll have to work to make audiences accept him as a man.

It is not simply a matter of his face. He is a man on the verge of middle age who has not had the experiences that force other men to leave their boyhoods behind once and for all. He has not gotten married. He has not had children. He has not had to live with his mistakes. Instead, he has had experiences that most other men can only dream of and has endured nothing but success — fame, respect, money, meaningful work, adulation. Many of his friends remark upon his maturity. But even they can't say how he acquired it.

"The Leo I know now is a man. The Leo I knew at nineteen was a boy," says Baz Luhrmann. Luhrmann directed DiCaprio in Romeo + Juliet, the movie that introduced him to the teenage market and set him up for the seismic success of Titanic. In a way, Luhrmann was the last to see DiCaprio before he became, in Luhrmann's words, "as big as the Beatles."

Now, twenty years later, he's directed DiCaprio in this summer's Great Gatsby. And he speaks of DiCaprio's maturity with a reverence born of surprise and relief. "I tell people that they have to understand that Leonardo's only ever been on a movie set. He knows nothing else. So I think it's a paradox. There's absolutely no question that he's grown and matured, but he's grown and matured in a way unique to Leonardo. Nobody knows the kind of fame that Leonardo knows, and it's far more common for people to become deranged by it. It's generally quite toxic. But somehow it hasn't been toxic for Leonardo. He's been very good at making choices for his self-preservation."

Leo was maybe twelve. He was on his way home from school with his mom. He saw a kid making an episode of a TV show on a street in L. A. He recognized the kid from auditions. That's mainly what he did in L. A., so he saw a lot of kids who were, on the surface, just like him — they were all animated by the same dream and had the same determination and deep down they were all just as desperate. But this kid, Tobey Maguire, he really was just like Leo: He grew up in L. A. and he was being raised by a single mom and he didn't speak, like, five languages and he just wanted — needed — to act. So DiCaprio told his mother to stop the car, like, now. "I literally jumped out of the car," he says. "I was like, 'Tobey! Tobey! Hey! Hey!' And he was like, 'Oh, yeah — I know you. You're... that guy.' But I just made him my pal. When I want someone to be my friend, I just make them my friend."

It was the beginning of a famous friendship; it was also the beginning of DiCaprio's effort to organize around himself the surrogate family he would need to survive what he was about to become. He couldn't have known the level of stardom that awaited him, and yet both DiCaprio and Maguire acknowledge that their friendship was no accidental adolescent alliance but rather an accomplishment of DiCaprio's overweening sense of purpose: "You don't become as successful as Leo if you don't know how to get what you want," Maguire says. DiCaprio wanted to be friends with Maguire, and with Lukas Haas and later with Kevin Connolly, in the same way that he wanted parts in movies. They were all child actors rather than simply children, and so they knew their way around the competition and rivalries that poison friendships formed in simpler circumstances — knew their way around the discovery that DiCaprio was not the same as them.

It was a discovery that Maguire made when, after DiCaprio beat him out for the lead role in This Boy's Life, Maguire got a part as one of his friends... and so had a chance to be on the set and witness the level of preparation that DiCaprio brought to his performance. It was a discovery that Connolly made watching DiCaprio play the mentally disabled boy in What's Eating Gilbert Grape, a role that earned DiCaprio an Academy Award nomination at the age of nineteen, and, in Connolly's words, "changed everything." No, it didn't change their immediate circumstances; they were still living in crash pads in Westwood and Studio City and roaming L.A. like a pack of wolves. But it changed Connolly's presumptions about his friend. He always thought — and still insists — that Leonardo DiCaprio is a "painfully normal guy." But he wasn't, really, at least in terms of what he could do in the dark room. And so it was going to be Connolly's task to help Leonardo DiCaprio lead the semblance of a normal life.

It worked as well as it could. Twenty years ago, when Baz Luhrmann invited him to Australia to start working on Romeo + Juliet, DiCaprio traded in his business-class ticket for five tickets in coach and brought his friends with him.

"I thought, He realizes he's never going home," Luhrmann says. "So he brought his home with him." Luhrmann was right, on both counts. The level of fame that DiCaprio achieved when most of his friends were still struggling to get parts was both liberating and obliterating. On the one hand, he could do anything — have any woman, make any movie. On the other... well, "I was like, Oh, my God. I really didn't understand what fame was and I didn't understand what being in a giant hit was and I didn't understand what a giant hit Titanic was compared with other giant hits. There was no rule book. There was nobody to navigate me through the experience of being watched all the time and nobody to tell me how to be normal when everybody is acting and looking at me differently."

He turned to his friends and shared the fruits of his fame with them. They were all the same guys, but now they became notorious — Leonardo DiCaprio's "Pussy Posse" of the late nineties — because he was notorious. But hell, that was long ago. Some of those guys became famous in their own right — Tobey Maguire for Spider-Man and Kevin Connolly for his role as the force of sanity in the life of a good-looking megastar on Entourage. And then they started having lives of their own, getting married, having kids. And DiCaprio didn't. Oh, he had a life, sure, but it was like, the same life, allowing for differences in scale. All the guy did was make movies. There were women, of course, some of them famous beauties, but, as he says, "six months of being on location or being off in Morocco or someplace like that is not the best thing for a relationship." He got a dog but had to give it to his mom to take care of because "if I had to feed it, it would starve and die." Over the last two years, he made three movies, Gatsby, Django Unchained, and The Wolf of Wall Street, and when he finally came home, his friends were like, "Dude, you don't even live here anymore."

No, he can't have a normal life. But his friends can. They were total wingmen when he was leading them through the high-life of L. A. and New York and Paris more than fifteen years ago. Now he's their wingman as they give him a tour of the kitchen, the patio, a glimpse of domestic comfort. Connolly lives in the same neighborhood as DiCaprio — "ten houses away," he says. So does Maguire. And so they go back and forth. They play basketball on Saturdays, they watch sports on TV, they talk about the work they want to have done on their houses or about nothing at all. "We have the most unimpressive conversations," Connolly says. "You wouldn't believe how unimpressive." And DiCaprio? He's Uncle Leo when he's in the neighborhood, and if that designation sounds inherently ridiculous, well, good — it's what he fights for, because it means freedom.

"People are always like, 'It must be so hard for you, not to be able to leave your house,'" DiCaprio says. "I'm like, 'No, I go where I want and do whatever I want all the time.' 'No, you walk down the street?' 'Yeah, I do all the time.' 'Really?' 'Yeah, all the time.' You have the feeling that they want to protect you from what they imagine your life to be like."

But what is his life like? Nobody knows, and when you tell him that nobody knows, he says, "Really? Huh — I thought it was the exact opposite." He has done his best to let us see him only in the dark, and as a result he appears to live his life at the extremities — he appears to live a life at once impossibly large and impossibly small. It is easy to miss him, easy to look at him and see a boy growing older without having to grow up. It is harder to see what his friends have the opportunity to see: a man, unusual only for the degree of his talent and the extent of his fame. They see a loyal and generous friend — a member of their weddings, a guy who served as a pallbearer at the funeral of Kevin Connolly's mother and who gave Kate Winslet away when she was recently married. They see a guy who happens to win most of the time but who has lost occasionally, with predictable results. Asked if Leo has ever been heartbroken, Connolly says, "Absolutely — big time. He has been 100 percent heartbroken by a girl." But they also see, by consensus, a guy "fiercely protective of his privacy," whose privacy they are obliged to protect. That this is something of a fiction — that if Leo has been made vulnerable by fame, he has also been heavily armored — is invisible to them by dint of the roles that they themselves play. They are not only protective of their friend Leo; they would not be in his life if they were not. He exists at the center of a protective network of which his friends are a part.

"His friends are supposed to be the measure of his normalcy," says a Hollywood producer who has worked closely with him. "But how normal is it for anyone to have the same friends he had when he was thirteen years old? Ask yourself — how many of your friends from that time do you still hang around with? Things change. But for Leo, nothing ever really changes."

A little while ago, he had to make a decision. It was a big one. He had to decide whether he wanted to star in Baz Luhrmann's Great Gatsby as Gatsby. Luhrmann had asked if he wanted to do it. It was a big, iconic role — "America's Hamlet," is what Luhrmann calls it — but that's not why DiCaprio had to think it over. Originally, the project belonged to Sony and DiCaprio has his deal with Warner Brothers, but that wasn't the reason, either. Luhrmann had been on the phone with DiCaprio, and he knew that DiCaprio was cautious about playing Gatsby for a very specific reason:

Gatsby is very good-looking.

Luhrmann had been through this before with DiCaprio. He had been through it when he asked DiCaprio to play Romeo opposite Claire Danes's Juliet. DiCaprio had made his name playing what were essentially character roles, and he understood that the glamour of Luhrmann's conception of Romeo would change his life. He'd been right. Now with Gatsby, he was looking at the same kind of decision. He had spent the decade and a half since making Titanic on the run from his beautiful face, from his compulsive movie-star charm, and from movies that required him to be attractive in order to work. He'd worked with Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, Christopher Nolan, Clint Eastwood, and five times with Martin Scorsese. He takes very seriously his responsibilities as a leading man. "There's so much more responsibility in being a lead," he says. "There's the arc of that character and how each of your decisions affects the story line. When I was in Gilbert Grape, I could spit spaghetti out and climb trees and make any noise I wanted, because Johnny had to move the story along, for the story to make sense." And now he was hesitant to be in another movie that to some degree was about his looks... .

"Getting Leonardo to make the decision to play Romeo when he was nineteen was high drama," Luhrmann says. "He said, 'I won't do that again' with Gatsby, and he did it again. It was the exact same thing."

What turned DiCaprio — convinced him — was the book. Luhrmann gave him a first edition, and DiCaprio says that he wound up reading it at least twenty times. He discovered a character who is "this peasant who is unaccepted by the American aristocracy," DiCaprio says. "He will never be them and he will never truly belong." He was not only attractive — Gatsby had to be attractive in order to manipulate people, and he had to manipulate people to achieve what Luhrmann calls a "noble cause — the love of a single woman." And once DiCaprio saw that attractiveness was fundamental to any true characterization of Gatsby, he decided to take it on. He wound up giving a performance in which "he's not hiding from the fact that he can be attractive onscreen," Luhrmann says. "Leonardo took the immense leap of not fearing the natural charismatic ability that Gatsby requires and that in many of his movies Leonardo has been shy of."

But first he had to call Tobey Maguire and ask him if he wanted to play the role of Gatsby's only friend, Nick Carraway.

The biggest decision he ever made was not really a decision at all. It predated decision making. It was something he remembered rather than chose. It expressed itself as a wanting, and ultimately as a need. He wanted that, until it became this — the life he has now.

"It's truly my first memory, wanting to do this," he says. "I went to a concert once when I was a little kid and ran up onstage, started dancing, started saying anything that came to my head. I was like a little vaudevillian. I did imitations of anyone who came to my parents' house, and that was my identity at school — if there were ten minutes to lunch and the teacher was done with the lesson, he'd say, 'Okay, Leo, get up there and do something.'"

His life became pretty simple after that. His first choice determined many of the choices that followed. The Leonardo DiCaprio who ran wild after the success of Titanic could do anything he wanted, but for all we could see, he only had to decide two things:

Which movie to make?

Which model to date?

He is an older man now, but not necessarily a more complicated one. He has many responsibilities, but they are almost exclusively the responsibilities of stardom. Indeed, the decision that he made in regard to Gatsby — and the decisions that he makes as the head of his production company, Appian Way — are in keeping with the decisions he began making when he was still a child. What's changed is his degree of power; as Warner Brothers president Jeff Robinov says, "I don't know of a movie that Leo has wanted to make that hasn't been made." And yet the agonizing decision of whether or not to make a movie that requires you to be attractive does not seem, on the surface, to be the kind of decision that would make a man of you. Has Leo ever had to make any other kind of decisions? Has he had to make the kind of choices that most people make routinely in the course of their lives — agonizing choices unrelated to the dictates of art and fame? Or was the die cast, when he, as a boy, as a child, chose to do exactly what he does now?

"There have been a lot of other choices," he says. "But you have to understand — in this industry there are a lot of other people who are passionate about becoming actors. You wonder who you are going to become. You're not even a formed man, and you try to decide what's going to become of you for the next eight or nine years. And I always thought of myself as the underdog because I didn't have nice enough clothes or maybe my hair didn't look good. And so you have to understand — getting your foot in the door is like winning the lottery. It's literally like winning the lottery if you get to have a career. And I've always felt Okay, now I've gotten this shot, and I'm lucky to have gotten this shot, and if I don't do this to the best of my ability — if I don't work my ass off and make a life of it — I've squandered this incredibly golden opportunity. And that's always been what has propelled me."

He is saying, in essence, that yes, the die was cast. He is also saying that as a very young man he had more responsibility for himself than many men do after they've ostensibly grown up. His life raises not only the possibility that the experience we regard as infantilizing — the experience of extreme celebrity — might provide as legitimate a route to "manhood" as the experience of disappointment and suffering; it raises the possibility that manhood, as an arbiter of meaning, barely matters. Ask Clint Eastwood why Leonardo DiCaprio is a fine actor and he answers in three words: "He enjoys it."

And ask Leo himself, after he cracks his neck, how he answers his own question — What makes me really happy? — and he responds as though the answer has been self-evident all along: "I think I'm doing it!"

One day, in 2010, Leo DiCaprio expanded the purview of the decisions he had to make. He still had to ask himself what movies to make and what model to date. But he also had to decide what species to save. He called Carter Roberts, the president of the World Wildlife Fund, and asked him to come to L. A. Roberts went. They met at a restaurant in Hollywood, and "we have this long lunch talking about the magic of having a champion for the cause of every animal." DiCaprio wanted to champion the tiger. He grew up in L. A. He used to go down to the La Brea tar pits to look at saber-toothed tigers drowned and preserved in tar and wonder how such creatures had disappeared from the earth; he used to go to the Natural History Museum and try to think of something else he wanted to do besides become a famous actor. And now that he is a famous actor, he doesn't just like tigers; he thinks a world without them — or a world in which they only live in zoos — would be a "fucking nightmare." What's at stake is not simply the fate of the tiger — but of wildness itself. "World leaders," says Carter Roberts, "like Vladimir Putin, like the king of Bhutan, and like Leo, see a little of themselves in tigers. They're at the top of the food chain, they're killers, and they're incredibly good-looking. What's not to like?"

Guy goes to Leo's house to make him a coffee. The guy's name is Todd Carmichael. He's an adventurer who has set records for wilderness trekking and who develops coffee farms in very remote and impoverished parts of the world. He spawns little economies by buying the coffee, roasting and selling it. He also believes that "every man should have his animal." Carmichael's animal is the Indonesian orangutan. When he heard that one of Leonardo DiCaprio's animals is the Sumatran tiger, he gave him a call. "I thought that the conversation would last two minutes. But it kept going and going, and by the end we had a product. I said, 'I'm going to make you a coffee.'"

He did not mean that he was going to grind beans and pour hot water through them. He meant that he was going to create a coffee for Leonardo DiCaprio. DiCaprio would put his name on it, and Carmichael would sell it under his brand name, La Colombe, with all profits going to the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. The coffee would be called Lyon. But first DiCaprio had to approve it. So Carmichael went out to L. A. to have lunch with Leonardo DiCaprio and create a Leonardo DiCaprio "taste profile."

The lunch took place at DiCaprio's house. The food was brought in. Carmichael offered different kinds of foods to DiCaprio and noted whether or not he liked them. "I'd give him some frisée, and he'd shake his head. And I'd say, 'So no bitters?' 'No, no bitters. No way, frisée!'"

In many ways, it was the quintessential Leonardo DiCaprio experience. It was kingly. It occurred in the house where he feels comfortable. It was for a cause, but it allowed him to exert control. Lyon coffee would exist as an expression of both his generosity and his ongoing efforts of discrimination. And he has to do nothing but lend it his Leo-ness, knowing his Leo-ness is enough.

And so Carmichael bought the coffee and roasted the beans, and when DiCaprio tasted it, he was amazed at how perfectly it captured him.

"I felt like a genius," Carmichael says.

He acts in his chair in the hotel conference room. He performs. He can't stop himself any more than he can stop himself from being what Baz Luhrmann calls "attractive." He is sitting in his chair, talking about his compulsion to collect "old stuff" — everything from bones to original movie posters — in an effort to see reports from an unfiltered world, untouched by the hands of media and fame. And he says that, for him, the ultimate unfiltered world is the ruin of Pompeii. You have to go, dude. You have to wake up and go early in the morning, when nobody is there, when there are no tourists around, and see the molds these people made in the ash at the moment they died, two thousand years ago. They're captured for all time in all these campy Nosferatu poses of death... and now Leonardo DiCaprio, in his chair, begins performing, begins assuming these "campy Nosferatu poses of death," curling up on himself, bringing his hands to his face, enfolding his cheeks with his long fingers, looking for all the world like a silent-film star himself as he mimics the awe and terror of a woman holding her baby in what she knows is the last moment of real life.

He never really stops performing after that. He's excited; he's an enthusiast; he likes to tell you where to go and what things to see. He's returned to L. A. after two years of making movies, and though he feels more comfortable with himself than ever before, he's also trying to decide whether or not to take a vacation. He's just cracked his neck and has just talked about asking himself what it takes for him to be happy. Now he goes on — "I'm talking about in any situation in life. In anything that might come up. I have a production company, I have a foundation, I have a lot of responsibilities. Not family — just a lot of responsibilities. But things take care of themselves when you're gone. Then you come back, and it's like, You gotta be here, you gotta be there, you gotta do this, you gotta sign that, you gotta read scripts, you gotta go to the photo shoot, you gotta do the interview, you have meetings, this person needs you, that person wants you, and it's like, 'Wait a second, can I just please... take a breath?'" And he keeps going like this, keeps talking faster and faster until he's a little out of breath, theatrically out of breath, and then he raises his hands again to his face like a long-dead silent-film star acting out the agonized ending of the long-dead inhabitants of an ancient Roman city, and with his lungs pumping like bellows he suddenly says—

"Oh, shit!"

And stops.

You really need to try his coffee. It's made from beans grown in Haiti, Peru, Brazil, and Ethiopia, and all its proceeds will go to the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation. But you really need to taste it, because it's him in some kind of distilled essence. It's not bitter. It's not sweet. It's not, well, anything really, except a rounded feeling in your mouth, a space where other tastes may grow, a presence defined by an absence. It's incredibly soft but also exquisitely confrontational — you'll have to decide what you think about it. You'll have to decide whether it's the Leonardo DiCaprio you've seen in the dark room or the Leonardo DiCaprio who lives in the light of day.

More from DiCaprio here.