From nothing more than a piece of bone from a child's little finger, the human family tree has gained another member, one who lived alongside modern humans perhaps as recently as 30,000 years ago.

Yesterday's revelation, that scientists in Germany had discovered – to their amazement – that the bone recovered from a cave in the mountains of southern Siberia almost certainly belonged to a new species of human, has sent ripples of excitement through academic circles. For the first time, the analysis of ancient DNA has rewritten the human story. Some 30,000 years ago, human life was far richer than we could have imagined.

Until recently, palaeontologists' view of human evolution was desperately lacking. Ask them to paint a picture of human existence 40,000 years ago, say, and they would mention modern humans, Homo sapiens, occupying vast territories. The only other hominid (a human or close relative) in existence back then, Homo neanderthalensis, was eking out a life alongside us modern humans, but its populations were in terminal decline. Then the Neanderthals became extinct around 25,000 years ago. That much was agreed upon.

Things changed in 2003. Field researchers working in caves on the Indonesian island of Flores uncovered remains of a diminutive human relative that lived at least 13,000 years ago. The Flores "hobbits" grew to be a metre tall as adults and could be traced back to Homo erectus, the forerunner of modern humans that left Africa 1.9m years ago. The hobbits' size is thought to be a direct result of their isolation.

Then there is the latest discovery, with which the number of early human species, or hominids, living 30,000 years ago has risen to four. In the space of a decade, the size of the human family has doubled.

And it's not just the cast list of the human evolution story that has had to be revised. Excavations of fossilised human remains have now led scientists to talk of three great migrations out of Africa. The first footprints leading off the continent were left by Homo erectus (the ancestor we share with the Neanderthals, with those hobbits, and with this new species of human). The next migration, around 450,000 years ago, was the Neanderthals. Then, perhaps as recently as 60,000 years ago, the first modern humans left to populate Eurasia and beyond – the humans from whom all of us alive on earth today are descended. The new species of human appears to fit in with none of these migrations out of Africa, and instead points to yet another great exodus, one that happened around 1m years ago.

To some scientists, even this fairly complicated picture is beginning to feel over-simplistic. "I don't think we can be absolutely certain about anything now," says Professor Terry Brown, an expert in ancient DNA at Manchester University.

What we do know is that the story starts in Africa, but that early humans then decided to leave. "There's no reason why a hominid should remain in Africa if the population increases," says Brown. "The natural thing for it to do is to move." The march out of the cradle of humanity may have been more of an ongoing wander, with early humans moving farther afield as and when they needed.

What's also known is that with the exception of the hobbits of Flores, every human species is thought to have evolved before making its way out of Africa. How we ended up with a number of different hominids is probably down to geography: species can split into two when groups of individuals become isolated from one another. When they stop interbreeding, the genetic makeup of each group drifts and diverges. They adapt differently to their habitats. Eventually, the differences became so large they cannot reproduce even if they tried.

In Africa – a very big place – small groups of thousands likely occupied disparate territories, and many splits may have occurred. Eventually, as the evolutionary clock ticked by, some Homo erectus embarked on a route that culminated in the Neanderthals. Others went down the route that led to modern humans. Still others, scientists now believe, became the new human species that left its little finger in a Siberian cave.

The most intriguing thing, perhaps, about this new discovery is its location. The bone was uncovered in an area where the remains of humans and Neanderthals have all been found from around the same period in history. Together, the evidence points to a time, between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago, when all three species were there. Did they ever meet? Did they make out? Did they fight? And why was Homo sapiens the last human standing? Do we owe not only the Neanderthals but this new species a big apology?

"It could have been that there was a period of occupation, where as one species moved out, another moved in. Ten thousand years is a long, long time and it is possible they never actually met," says Brown. "The alternative is that they may have been having parties every Saturday night, all three of them, getting together and talking about the Neanderthals down the road."

If they did live alongside one another, they needn't have been in constant conflict. Related species of other animals – big cats for example – share territories, yet show their neighbours nothing but cool indifference. Conflict is only likely when there is competition for the food, mates or shelter. That said, the three human species probably all hunted large mammals, including woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos, the remains of which have been unearthed in the area.

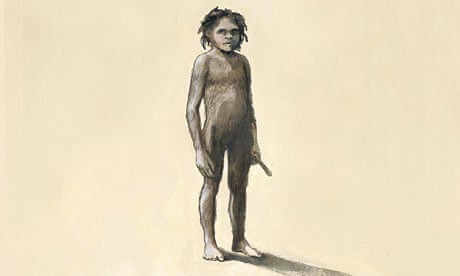

So what is the fourth human to be called? In lieu of a formal name for the new species, Svante Pääbo and Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig – who extracted and analysed the DNA from the finger bone – gave our latest ancient relative the nickname "X-woman". From the size of the finger bone, they suspect it belonged to a child aged between five and seven years old, but whether it was a boy or girl is unknown. The nickname is a nod to the laboratory tests they used to identify the creature as something new to science: they examined DNA locked up in tiny organelles called mitochondria, which are passed down the maternal line only.

What genetic material the scientists have analysed so far points to an early human that shared a common ancestor with modern humans and the Neanderthals 1m years ago. (Modern humans and Neanderthals split from their own common ancestor 500,000 years ago.)

The work at the Leipzig lab is ongoing, however. In the next few months, the team expects to have sequenced the creature's full genome, a step that will do more than confirm whether it is a new species or not. One of the perennial questions in human origins research – and one genetics is uniquely well-placed to answer – is whether co-existing human species mated with each other. Detailed studies of several Neanderthal genomes by the same laboratory have found no compelling evidence that interbreeding happened between modern humans and Neanderthals. But only further work will rule it out, or in, completely.

There is good reason to suspect, however, that, even if our ancient ancestors never got up close and personal with each other, we played a role in their demise. The Neanderthals died out in Europe soon after the arrival of modern humans. A coincidence? Some scientists put the blame on climate change, and suggest the Neanderthals – who were probably not so different from us, using tools, possibly talking to each other – were poorly equipped for the upheaval that ensued. But the Neanderthals were hardy creatures and died during the middle of the last ice age, not during the major period of transition at the end. More likely, say some scientists, was that Homo sapiens out-competed the Neanderthals for food and other crucial resources.

The discovery of this new human species, one that lived at the same time as modern humans and the Neanderthals, does nothing to make this uncertain picture any clearer. Now there are two human species that died out, if not in our presence, then certainly in our proximity. "That makes the whole argument more interesting and it is going to be the debate that is had over the next 10 years," says Brown.

Casting an eye over the last 6m years of human evolution, from the moment we split from a common ancestor with modern apes, to the rise of Homo sapiens, it is hard not to notice that scores of other early human species have come and gone: evolutionary experiments that failed. And yet we prevailed. Why should Homo sapiens be any different? Could we die out too at some point? Or are we destined to be just another branch on the tree, one that paves the way for the next, more evolved version of a human being?

As for dying out, we are safer, perhaps, in being able to control our environment – to some extent at least. As to us evolving into something different, some biologists believe that Homo sapiens has to all intents and purposes stopped evolving, or at least that the pace of our evolution has slowed. That could leave us more vulnerable to new diseases or wild changes in the environment. Then again, change could come in more dramatic fashion.

"If a global disaster wiped out much of the human race, leaving only a population of few hundred thousand, they would probably evolve into something very different to us," says Brown. A passing asteroid might thump into the planet and leave only isolated pockets of Homo sapiens, living in a habitat unrecognisable to the world today. Some groups would inevitably die out, but those that survived would eventually carry on the human line under a new name.

But then there are no certainties here, and indeed the history of our understanding of human evolution shows us that whatever we believe now could be turned on its head within a matter of decades. It used to be believed, assumed rather, that Neanderthals were our ancestors – the cave men that came before us. Of course that turned out not to be true: they lived alongside us. And now it turned out that these others, the fourth humans, did too.

The really good news is that against the backdrop of this more academic debate, against all this uncertainty, there now lies a realm of new opportunity and new understanding thanks to the potential of DNA analysis. The discovery of X-woman marks a first in using genetics alone to identify what many palaeontologists believe must be a new human species. But this is also one of the earliest attempts to look at ancient DNA from human remains.

The fossil record we have for humans is patchy and incomplete, but tiny fragments that have been labelled, over the course of many decades, as Homo sapiens, or Homo neanderthalensis, or Homo erectus, sit in museums and laboratories all over the world.

Are there fragments of bone from other unknown humans among them? "It could be that there is a whole load of human ancestors out there that we don't know about yet, and I mean five, six, or seven types of human," says Brown. "Everything is wide open now."