In May 2003, David Grossman, one of Israel's most celebrated novelists, began writing a new book. It was to be about what the Israelis euphemistically call "the Situation", which was a little odd because, for the past decade, he'd carefully avoided writing about politics, in his stories, if not his journalism. It was not just that he'd long felt that almost anything he could say had already been said by one side or the other. There was the danger that such a story, even in his deft hands, would be creaky and polemical. Now, though, he felt suddenly that he couldn't not write about it. Grossman's eldest son, Yonatan, was six months from completing his military service and his younger son, Uri, was 18 months from beginning it. His feelings about this – in Israel, men serve three years – were so acute, it seemed they would push the pen over the paper for him.

The story came quickly. It would be about a middle-aged woman, Ora, whose son, Ofer, only just released from army service, has voluntarily returned to the frontline for an offensive against one of Israel's many enemies. Ora, having moved from celebration to renewed fearfulness in a matter of hours, is in danger of losing her mind. She has no idea how she will get through the next weeks or months. Then, in a fit of magical thinking, it comes to her. She will mount a pre-emptive strike of her own. She will simply go away, absent herself from her home and her life. That way, she reasons, she will not be there when the army "notifiers" come to tell her of her son's death. And if she is not there, perhaps he will not die. After all, how can a person be dead if his mother isn't at home to receive the news of it?

Grossman started writing and as he did, he, too, indulged in a little magical thinking. He had the feeling – or perhaps it was just a fervent hope – that the novel would keep Uri safe. Every time Uri came home on leave, they would discuss the story, what was new in the characters' lives. "What did you do to them this week?" Uri used to ask. He also fed his father useful military details. This went on for a long time and it seemed for a while as if the charm was working. But on 12 July 2006, following Hezbollah attacks on Israeli soldiers on patrol near the Lebanese border, war broke out. Over the course of the next 34 days, 165 Israelis (121 of them soldiers), an estimated 500 Hezbollah fighters and 1,191 Lebanese civilians were killed.

Grossman was terrified for his son, a tank commander, but he was not, at first, opposed to the war. Though a determined lefty as far as Palestine goes – he is against the occupation of Palestinian territories – he believed that Israel had a right to defend itself against Hezbollah which, unlike the majority of Palestinians, is committed solely to destroying Israel. As the weeks went on, however, he began to think that Israel should show more restraint. At the beginning of August, together with two other great Israeli writers, Amos Oz and AB Yehoshua, Grossman appeared at a press conference in Tel Aviv, demanding that the government negotiate a ceasefire. "We had a right to go to war," he said. "But things got complicated... I believe that there is more than one course of action available." He did not mention that his own son was on the frontline. It was not relevant. He would have felt exactly the same had Uri been safely at home.

The Israeli government eventually accepted a UN-brokered ceasefire which came into effect on 14 August. But this was too late for Grossman and his family. On 12 August, in the dying hours of the war, Uri, who was just 20 years old, was killed when his tank was hit by a rocket; he and his crew, who were killed with him, were trying to rescue soldiers from another tank. The notifiers came to Grossman's house at 2.40am. He heard the voice over the intercom, and he knew what was coming. Between his bedroom and the front door, he decided: "That's it – life's over." But the strange thing is, it was not. The Grossmans buried Uri; his father's simple but piercing eulogy was reprinted in newspapers around the world, including the Observer; and then the family sat shiva (a period of mourning during which time a Jewish family receives visitors).

The day after the shiva ended, Grossman returned to his book. "I went back to it for an hour," he says, surprise registering on his face even now. "Then I had to come back home. But the next day, I added 10 minutes, and the day after that, another ten. Yes, it was hard. I was going straight to the place that frightened me most. On the other hand, it was the only possible place for me." The result – To the End of the Land – was published in Israel in 2008 and arrives here, in the most beautiful translation, this week. What can I tell you about this book? I'm not sure. Only that I loved it. And that it tears at your heart. And that when I heard someone comparing Grossman with Tolstoy, and his novel with War and Peace, I did not scoff.

It is blazing hot in Jerusalem and, as usual, the city is a knot: tight with anger, cinched with frustration. The traffic is so heavy, it takes a taxi 20 minutes or more to move a single kilometre, but walk to your destination, as I've just done, and your dress will be sopping wet, the straps of your sandals will have flayed your feet like whips. Forget the holy sites, the bearded priests and the shawled rabbis. On a day like today, the visitor seeks the blessing only air conditioning can bestow: cool, crisp and calming.

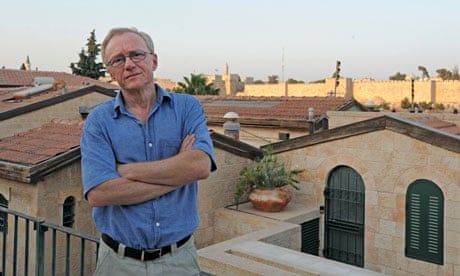

I meet Grossman in a coffee shop in Mishkenot Sha'ananim, a venerable Jewish neighbourhood just outside the Old City walls. The view from the window is of a pomegranate tree, the Hagia Maria Sion, formerly known as the Abbey of the Dormition, where the Virgin Mary is said to have fallen into eternal sleep and, following the curve of the next hill, the sombre grey line of the barrier that separates the citizens of Jerusalem from those of the West Bank.

The room is deliciously cold, (goosebumps are already rising on my shins), but the calm I feel, the sense of benediction, is all to do with Grossman. He once said that the effect of regular wars and prolonged uncertainty can be seen in the way Israelis drive (people are prone to honking their horns and yelling out of their windows). But you can no more imagine him going mad at an intersection than you can picture him inviting Binyamin Netanyahu out for beer and pizza.

Grossman radiates wisdom, modesty, kindness and, above all, a sort of stillness: contemplative and tender, but steely, too. This is not to say that the darkness is all behind him. He warns me that there are some things he cannot talk about, will perhaps never be able to talk about, and I cannot look at his heart-shaped face, his big, marsupial eyes, without worrying about manhandling him. Grief, inasmuch as I'm acquainted with it, makes a person feel, among many other things, like an over-ripe peach, prone to bruises and watery leaks.

For his own part, he likens it to exile. "The first feeling you have is one of exile," he says. "You are being exiled from everything you know. You can take nothing for granted. You don't recognise yourself. So, going back to the book, it was a solid point in my life. I felt like someone who had experienced an earthquake, whose house had been crushed, and who goes out and takes one brick and puts it on top of another brick. Writing a precise sentence, imagining, infusing life into characters and situations, I felt I was building my home again. It was a way of fighting against the gravity of grief." The merest flicker of a flinch. "This used to be so hard to express... but now, when I talk about it, I feel able to say that it was a way of choosing life. It was so good that I was in the middle of this novel, rather than any other. A different book might suddenly have seemed irrelevant to me. But this one did not."

Grossman's heroine, Ora, whom the American novelist Paul Auster has already likened both to Tolstoy's Anna, and Flaubert's Emma Bovary, decides to hike in Galilee for the duration of her country's latest war. She takes with her an old love, Avram, a veteran of the Yom Kippur war and a former PoW. While they walk, they talk. She tells him about Ofer, describing her boy at every stage in his life, carefully bringing him to life (Avram has never met him). Slowly, an absence becomes a presence. The novel, then, works as kind of memorial: not only to Uri, to whom it is dedicated, but to Ofer, who may, or may not, be dead. After Grossman had finished writing it, he handed it to Yonatan, and to his wife, Machal (he also has a daughter, Ruti, but she was too young for this book at the time). "It wasn't easy for them to read it," he says. "I think it was only the second time they read it that they understood that it could be a source of comfort to us all. I'm not describing our family, but there are always moments [when the two collide]. And yes, when someone dies, they're gone and yet they are still so present."

Four months after Uri's death, Grossman addressed a crowd of 100,000 Israelis who had gathered to mark the anniversary of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. His speech was beautifully controlled, but quietly furious. He denounced Ehud Olmert's government for a failure of leadership, a failure which would ultimately damage the Jewish state, and he again argued that reaching out to the Palestinians was the only hope. "Of course I am grieving," he said, anxious that Olmert and his cronies might dismiss his speech as the outpourings only of a bereft father. "But my pain is greater than my anger. I am in pain for this country and for what you and your friends are doing to it."

I understand that he wants to separate his grief and his politics, but does he think, now, that his loss has changed some people's opinions of him all the same? "Yes. There were people who stereotyped me, who considered me this naive leftist who would never send his own children into the army, who didn't know what life was made of. I think those people were forced to realise that you can be very critical of Israel and yet still be an integral part of it; I speak as a reservist in the Israeli army myself."

His novel provoked a strong reaction in Israel. "Some of my books in the past have aroused hatred [notably his collection of reportage, The Yellow Wind, a sympathetic account of life in the occupied territories]. Not this one. I think this one allowed people to give up on the need to be a fist, to remember the nuances, to ask themselves: what does it mean to be a human being in this situation? Our curse is that all of us become representatives; we congeal. But we need to feel our inner doubts, our contradictions."

Was it horrible having to grieve in public? He must have feared that his son would be adopted as yet another symbol of the Situation. "I'm not sure it was horrible. One burden is at least taken away [when you are a public figure]: you don't have to tell people what happened, because they know. We found our way. We're very private people. We are a close family and we have a wonderful, devoted group of friends. What happens outside that... well, it depends how people approach me. Most approach me with tenderness and sensitivity. There has been a lot of warmth. But I made it clear from the beginning that I don't ask for special privileges. I don't want people to say: ah, because he suffered this, his opinions are this. My opinions are not my emotions. I spoke in Rabin Square, but I only do [public] things that I would have done before.

"I'm not a rational, cold person. On the contrary, so much of the politics is emotional here, and the two peoples involved are very emotional, so you must be attuned to emotions very precisely. But the bottom line must be logical. You must not surrender to the primal urges of revenge. I just do not see a better solution than the two-state solution. I'm more sad, and maybe desperate, but not in a way that paralyses me." He pauses. "Maybe I cannot afford the luxury of despair. Maybe. Or maybe it's a question of personality: I cannot collaborate with despair because it humiliates me to do so."

All the same, he cannot feel hopeful at the prospect of more (American-brokered) talks. "I think our prime minister is the only person who can change our destiny for the better. He has a lot of credibility here. The question is: does he really believe in peace with the Palestinians? And I'm afraid that the answer is no. Even if he taught himself to utter the words 'two-state solution', he deeply mistrusts the Palestinians."

David Grossman was born in Jerusalem in 1954; he is the elder of two brothers. His mother, Michaella, was born in Palestine; his father, Yitzhak, emigrated from Poland with his widowed mother at the age of nine. "My mother's side of the family was religious and Zionist," he says. "They were poor. My grandfather paved roads in the Galilee, and he used to buy and sell rugs; my grandmother was a manicurist. On my father's side, well, there was this little sweet grandmother, so wrinkled, so tiny. She came after she was harassed on the street by a Polish policeman. This woman. She'd never before even left the little region where she'd been born. But she took her daughter and her son, and she took a bus, and a train, and a boat and she came to Palestine at the end of the war and cleaned rich people's houses. And she wasn't even religious!"

Grossman's father was first a bus driver, then a librarian, and it was thanks to him that his small son – "a reading child" – was able to indulge his love of books. He grins. "He gave me many things, but what he mostly gave me was Sholem Aleichem." Aleichem, who was born in Ukraine, is one of the greatest writers in Yiddish, though he is now best known as the man whose stories were the inspiration for Fiddler on the Roof. Grossman's father, like many men of his generation, never spoke of what he had left behind. "Then, one day, he gave me a book by Sholem Aleichem, and he said, 'This is how it used to be over there.' Why do I remember it? Because the expression on his face was one I hadn't seen before. It was the smile of a child. I started reading. The books are in archaic language and I struggled. But I kept going because I felt: this is the code for my father. I read them all. I devoured them. I inhaled them. I read them as a child today would read Harry Potter.

And I was sure that the shtetl continued to exist parallel to my life in Israel. Only when I was nine, and we were marking Holocaust Day at school, did it occur to me that this was not the case. I remember standing on the hot asphalt in my white shirt and my black trousers and I heard all these big words: victims, six million and so on. And I thought: they're talking about the people in Sholem Aleichem. You see, the Holocaust belonged to the adults. When you entered a room, they would stop talking. Sometimes, you'd overhear something: he lost his first family in Treblinka. But what was Treblinka? Where had he lost them? Would he find them again? So, suddenly, to understand the immensity of the loss... all the people I'd read about, they'd vanished, just like that. I was really shocked!"

Grossman had an aunt who'd been in Auschwitz and her camp number was tattooed on her arm. "When I was a child, it haunted me. I put it in a novel. The character thought the number was like the code on a safe and that if he could only crack it, a new grandfather, warm and friendly, would jump out of his old grandfather. When I got married, my aunt covered her number with a sticking plaster, so as not to cast gloom over the day, and I must tell you that is still one of the strongest memories of my wedding. My heart flew out to her. I thought: how terrible it is that you feel you must be apologetic about what was done to you."

In 1967, when Israel won the Six Day war, Grossman was 13. He remembers it vividly and believes that the memory helps him to understand some of the resistance on the part of Israel to ending the occupation. "If you want to understand, you have to go there; you can't deny it. The month before the war, I thought I was not going to live. I took the Arabs very seriously, just as I take them now. I heard a voice on their Hebrew propaganda station promising to come and kill us and to rape our mothers and to throw us into the sea. Then, the first night of the war, when Israel demolished their airforce, and it was clear we were going to win, there was this switch. To feel this miracle! To know we were strong and that after only six days we had become an empire.

"You could see how it changed the way people walked and talked. The arrogance of the talk! The sexual connotations that they used to describe what we did to them! I remember my first visit to a newly occupied place. It was two minutes away from here, in the Old City. I want to be very precise. I don't want to beautify my actions. The Arab population was overwhelmed and they looked at us with a mixture of fear and asking for mercy. We walked in their streets and we felt like gods. For the first time in our 2,000-year history, we were the strong ones. It's very hard to resist that. We indulged ourselves in all the feelings we had been deprived of."

In 1971, Grossman began his national service. "I worked in intelligence and most of it I liked. I left home, I was independent. I felt I was doing something important, that I wasn't doing anything against my principles." He served in Sinai, where there is more sand than people, and although he was in the army when the Yom Kippur war broke out in 1973, he saw no action. Where did he stand politically by this time?

"It was a few more years before I started looking at reality, at the places where we are wrong, where we have gone towards the abyss. Only gradually did I start to formulate what was wrong, and what should be done; it wasn't easy. It didn't make me very popular among my close friends and family. It was a lot to do with my wife and her family [he and Machal, a psychologist, met while doing military service]. They acquainted me with other ways of seeing this reality." So she agrees with you? Laughter. "No, I agree with her!" What about his children? "They are OK. They come with me every week to the demonstrations in Sheikh Jarrah [in east Jerusalem]. We are demonstrating against settlers taking over houses in Palestinian neighbourhoods, but it's a kind of weekly reserve service against the occupation, too. Sometimes, it gets violent. Some weeks ago, we were beaten by the police." How dare they beat David Grossman? He smiles. "I don't know if they know me at all."

After university, Grossman began working in radio, where he'd once been a child actor, eventually becoming an anchor on the Israeli equivalent of the Today programme. In 1988, however, he was sacked for refusing to bury the news that the Palestinian leadership had declared its own state and, for the first time, conceded Israel's right to exist. "They were so nasty to me. It was a little scary. I found myself in the middle of this very public affair, my name on the front pages. It was talked about in the Knesset. But I learned a lot about how a big organisation can act against an individual, and it was also a blessing because I had to turn completely to writing."

Had he always known he would be a writer?

"Yes. I knew it from a very young age. The first time I met my wife, this is what I told her. It was something physical, a piece of a jigsaw falling into place." Since then, his work has been translated from the Hebrew in which he always writes into 30 languages and he has won numerous prizes. He is unstoppable. Since delivering To the End of the Land, he has written a children's book, an opera for children and a handful of poems. "I feel poetry is more the language of grief than prose."

I tell him that every time I travel to Israel, peace feels further away. He doesn't disagree. "People who are born to war, programmed by war, their entire vocabulary is taken from war. Each step by the other side is regarded as a trick, or a trap, or a manipulation. It's tragic and we might not have the power to redeem ourselves from it. This is why we desperately need help from the outside. Time and again, we choose warriors to lead us, but maybe by always choosing warriors, we doom ourselves always to be in wars. Neither side wants to do what will benefit the other. They will take out one eye only so long as the other side loses two. Israel stands at a crucial point in its history, each step possibly fatal. But the way forward is so psychologically demanding, so threatening, we are stuck." He thinks the Israeli boarding of the Turkish boat bound for Gaza last May – nine activists were killed – was pure folly. "It was stupid. We had months to prepare. Why did we choose the belligerent way? Allow them in! Even if there had been terrorists onboard, it wouldn't have changed anything. Just show some sympathy."

Meanwhile, life in Israel grows somehow narrower. Grossman's Arabic is almost as fluent as his superlative English, but it is harder and harder to maintain links with Palestinian friends, let alone to travel there. "I spoke three weeks ago to a dear friend, the writer Ahmad Harb..." He sighs. "Between us, there is the mutual disappointment of people who had a common dream and who saw it evaporate. But I know he continues to fight in his society exactly as he knows I do in mine. We are like two groups of miners digging from either side of a mountain; we know we will meet in the end." The settlers? They are distorting an Israeli idealism he still holds dear. "The emotional investment we put into the occupation! As Gershon Sholem said, 'All the blood goes to the wound.' We are not taking care of ourselves. We are looking in the wrong direction. The settlement movement might really ruin us."

Grossman longs for Israel to be more than just a shelter for the Jewish people; he wants it to be a home. "And it will not be a home unless we have peace with our neighbours. In a home, you're comfortable, you breathe with both lungs. Here, we breathe with only one and we are suffocating. Believe me when I tell you that it is so much more important than being the dominator of this valley or that hill." He thinks most "sane" Israelis know this. What needs to happen next is that, somehow, they must close the gap between what they know and what they do. Not that he regards peace as a Hollywood ending. "It will be difficult. If there is peace, there will have been heavy compromise and that means a lot of angry and vengeful fanatics on both sides. They will do anything they can to assassinate it. They will bomb themselves here and there. But the alternative is worse. If we have no peace, the circles of bloodshed will become even more violent and hateful."

We have been talking for almost two hours. Grossman has a wedding to get to and there is the traffic to consider and... he shows me his palms, apologetically. "I've talked too much," he says. I disagree. There is something powerfully sustaining in listening to him talk: it means he is still with us. He nods. "I would not have chosen this catastrophe," he says. "But since it happened, I want to explore it. I feel I was thrown into no-man's-land and the only way to allow my life to coexist with death is to write about it. When I write about it, I'm not a victim. It is strange and unexpected to discover this. The great temptation is not to expose yourself to these atrocities. But if you do that, you've lost the war. The language of war is narrow and functional. Writing is the opposite. You describe your reality in the highest resolution even when it's a nightmare and in doing so, you live your own life, not a cliche others have formulated for you." On that terrible night in 2006, he told himself, as he walked from the bedroom to the front door, that life was about to end. "That's what I felt at that moment. But I was wrong. Life is different, but it's not over."

David Grossman will talk about his new novel on Thursday at the Friends House, Euston Road, London NW1, at 7pm. Tickets cost £15; go to jewishbookweek.com