"Shakespeare never went to Venice, Homer never went to Troy, Dante never went to Hell." The relationship between artists and their source material can be oblique to the point of non-existence, and the seven founder members who in 1848 declared themselves to be the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood knew little about Raphael and less at first hand about Italy, which none of them had seen. It was in London, among the soot-stained terraces of Bloomsbury, that they met to further their passionate resolve to transform British art. They wanted "to have genuine ideas to express", as one of them, William Michael Rossetti, put it later, and they were "to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them".

Like many rebels, they were clearer about what they were against – the Royal Academy, the older generation and the "slosh" school of painting – than what they were for. Since Raphael was considered the pinnacle of classical art, they would depose him; they would prefer his supposedly primitive predecessors. It was William Holman Hunt who suggested the term "pre-Raphaelite", thus setting in train more than a 150 years of critical debate and art-historical hair splitting. To their admirers and detractors alike, the pre-Raphaelites would remain essentially English. Their work had more to do with the questions that troubled Victorian London in an age of revolutions abroad and unrest at home, and with their own, often turbulent private lives, than with the real Italy.

It was idea of Italy in poetry, romance and national prejudice that echoed through the paintings, determining how they were seen, criticised and praised. Among the first to take issue with the name and its implications was Charles Dickens, who had fun in the journal Household Words complaining about "this terrible Police" as he called them in 1850 "that is to disperse all Post Raphael offenders". What next, he wondered: pre-Newtonian science perhaps, or pre-Chaucerian verse? The target of his sarcasm was a work that had nothing apparently to do with Raphael or Italy. It was a painting by John Everett Millais of the young Christ in his father's workshop. It was the realism that offended Dickens and many others, with Mary shown as a simple peasant woman, "horrible", he thought, "in her ugliness". To his friend Daniel Maclise, however, Dickens confided the underlying reason for his hostility. "If such things were allowed to sweep on," he wrote, "three fourths of this Nation would be under the feet of priests, in ten years." To him, as to many other Englishmen, pre-Renaissance Italy meant the threat of Roman Catholicism. On Guy Fawkes Night that year, the newly appointed Cardinal Wiseman was burned in effigy.

What Italy really meant to Hunt, Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the three most important members of the original brotherhood, was certainly a sense of the forbidden, whether Anglo-Catholic, as in Millais's case, or romantic. For Rossetti, whose father was an Italian political refugee, there was a personal identification with a tantalisingly half-known personal history. But most of all, their Italy was an imaginative space in which to develop their art – a space that had become briefly unfashionable with the artistic avant-garde. While tourists and collectors still went south, the artistically minded among the rising generation espoused the Gothic revival and the north, avoiding Italy as the home of classicism.

The person who made Italy fashionable for the contrarian young was the critic John Ruskin, who was taken there by his parents. Later, as he began to explore it for himself in the early 1840s, he encountered the so-called "primitives" and began to alter his own style of drawing accordingly, making detailed studies that were not picturesque but truthfully "ugly", as he put it, in their recording of the facts. It was the second volume of his Modern Painters in which he extolled the brilliance of Fra Angelico, Tintoretto and others who "crowned the power and perished in the fall of Venice", that lit the trail of enthusiasm that became the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. Ruskin's descriptions of the art he admired urged imitation, but not of a literal sort. He extolled "moral as well as material truth"; the "imagination associative", he told his enthusiastic young readers in Gower Street, "was the grandest mechanical power that the human intelligence possesses".

No critic has ever exercised more influence than Ruskin did over high Victorian England. Not only did the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood spring largely from the vision held out in Modern Painters, but his account of Italian architecture, especially the use of coloured brick and stone inspired the hundreds of Victorian Venetian buildings that spread across the country after 1850. As a vigorous Protestant himself, Ruskin intervened to rescue his protégés from the opprobrium of Dickens. The year after the attack in Household Words he wrote to the Times to reassure the nation that, despite their "unfortunate though not inaccurate name", these young men were not Romanists; they were in search simply of artistic integrity and "stern facts" rather than the "fair pictures" which had taken over art after the time of Raphael. They would paint either directly from nature, "what they see", he promised, or "what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent".

This second alternative was less of a manifesto than a carte blanche, and despite the pre-Raphaelites' enduring reputation for painting directly from nature, many of their subjects were highly mediated, the details taken from literature and invention as much as observation. Millais's first exhibition picture as a pre-Raphaelite was Isabella. Based on a story in Boccaccio as retold by Keats, who hadn't been to Italy either, it is set in an interior that looked as much like Pugin's House of Lords, opened the same year that Isabella was shown, as 14th-century Italy. It was Keats and Browning who continued to inspire the first pre-Raphaelites. None of them ever got to know Italy well, and Rossetti never went at all.

In spite of which, as Ruskin followed Modern Painters with The Seven Lamps of Architecture in 1849 and The Stones of Venice in 1850, Italianate balconies and polychrome churches started to appear all over England. The Victorians began to enjoy the idea of themselves as latter-day Venetians, independent merchants at the centre of a great trading empire. Yet as William Butterfield, architect of All Saints church Margaret Street in London, put it, "I am . . . persuaded that an Architect gets but little by travel. I am only glad that I had made up my own mind about a hundred things in art before seeing Italy." In Butterfield's densely decorated and dimly lit churches, as in Millais's and Rossetti's paintings, where scenery and figures are flattened to the point of pattern, everything external is excluded that might dilute the power of imagination. What after all might be "the actual facts" of the moment when Dante is spurned by Beatrice? There can only be an emotional truth conveyed by tension between hieratic figures on whose exchange of glances no glimmer of outside reality intrudes.

Among the wider pre-Raphaelite circle some did make the real Italian landscape their subject. But on the whole they were less successful. Ruskin's critical arguments, if followed too literally, could lead to disappointment, as even John Brett, arguably the best of them, was to find. A follower of Ruskin, he took his advice about painting from nature and spent five months working in and near the Val d'Aosta. The resulting picture was accepted at the Royal Academy only to be described by Ruskin as showing no more than "what a Piedmontese valley is like in July" and being in consequence just "Mirror's work, not man's". Sensing perhaps the unfairness of this, Ruskin at least had the decency to buy the picture himself.

Beyond the inner circle of the brotherhood new and younger admirers of pre-Raphaelitism began to emerge. This second generation was more willing to travel, though they went in search of the author of Modern Painters as much as Tintoretto. Ruskin actually paid for the young Edward Burne-Jones to visit Italy in the autumn of 1859. Travelling with his fellow artist Val Prinsep, he piously followed in the master's footsteps: "Ruskin in hand, we sought out every cornice, design or monument praised by him." Though he came to regard Italy as a second home, Burne-Jones was not much more open to its direct influence than Rossetti.

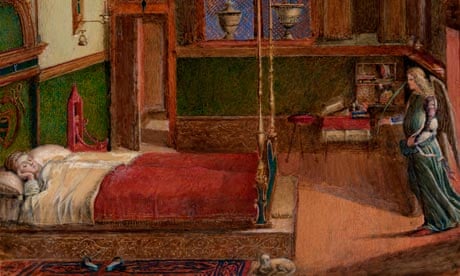

Gradually, and somewhat to Ruskin's irritation, Burne-Jones developed ideas of his own, daring to admire Michelangelo and rediscovering Botticelli. In introducing Ruskin to the work of Carpaccio, however, he repaid the debt of influence. Ruskin was captivated by the paintings of the Legend of St Ursula, especially the scene showing Ursula visited by an angel in a dream, and he made a detailed copy of it. Yet as so often in the pre-Raphaelites' engagement with the Italian, the resolve to depict what was there – to educate and reform national taste – was also a way of treating what lay beneath: currents of troubled emotion and frustrated desire. Ruskin's St Ursula is yet another rich and airless interior, occupied by another of the doomed, semi-conscious young women who haunt these pictures.

Over the decades their imaginary Italy had become the landscape in which the tangled reality of the artists' love lives was played out. By the 1870s, the freshness of the early dream had been tarnished by bitter experience. In Ruskin's increasingly disordered imagination Ursula became identified with, Rose La Touche, with whom he had been obsessively in love from her teens until her death at the age of 27. Copying the picture tipped him into one the psychotic episodes that blighted his later years. He had already separated from his wife Effie, who obtained an annulment on grounds of non-consummation, and was now married to her husband's early disciple Millais.

For Rossetti, the adultery of Paolo and Francesca, the tragic lovers whom he had depicted in 1855, had parallels with his feelings for William Morris's wife Jane, and he was haunted by another ghost, that of Lizzie Siddal, his model, later his wife, who committed suicide two years after they married. Rossetti buried his poems in her grave, only to exhume her and them later, and in her last incarnation, in his work as Beata Beatrix, a vision of Dante's mistress at the point of death, there is an air of exhumation too. Rossetti reworked the image over decades and came to see it, as Ruskin saw Ursula's dream, as a visionary moment, "a spiritual transfiguration", imbued with morbid eroticism.

Such complicated passions were reflected in a stronger palette. The more highly-coloured and voluptuous influence of the renaissance replaced that of the primitives, and for such insoluble situations there was no narrative answer. Scenes from Boccaccio and Dante gave way to static, monumental figures whose threat, or promise, only hint at what comes next. In Holman Hunt's Il Dolce Far Niente, a painting begun with one model with whom he was obsessively in love and finished as a portrait of Fanny Waugh, whom he married, the subject arches languorously towards the viewer. Meanwhile across the Channel, impressionism was transforming landscape art with new ideas of painting from nature, but the pre-Raphaelites remained untouched, involved as they had always been in a domestic English dream.

The Pre-Raphaelites and Italy is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until December. www.ashmolean.org

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion