It has been a week like no other in China. There have been allegations of poisoning, corruption, extortion and political intrigue spanning three continents. Every day new shockwaves have rippled out from the death of British businessman, Neil Heywood, who is now at the epicentre of Beijing's biggest political earthquake since the Tiananmen protests of 1989.

In Britain, MPs are demanding to know if Heywood was a UK government spy. David Cameron has held urgent meetings in Downing Street with China's propaganda chief, and foreign secretary William Hague has called for an internal investigation into the handling of the case by consular officials.

Washington is also being dragged into the morass, with details emerging this week of the terrified chief investigator Wang Lijun's bid for refuge at the US consulate in Chengdu in February – and the stand-off that followed as the building was surrounded by Chinese security personnel demanding he be turned over. Throw in additional – apparently untrue – rumours of military coups in Beijing, lovenests in Bournemouth and claims of murder and torture in Chongqing, and the story – shaped largely by leaks from the Chinese authorities – could come from a Le Carré thriller.

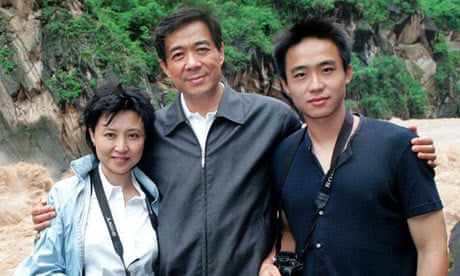

The victim is a Jaguar-driving British businessman with murky links to a corporate intelligence agency. The alleged villain is a Chinese lawyer, Gu Kailai, described by some as an unforgiving "empress". Her husband, Bo Xilai, was one of the most powerful men in China, who was betrayed by his closest ally, first to a foreign power and then to his rivals in Beijing.

Key facts remain elusive. Evidence of a crime even more so. But enough details have emerged over the past few weeks to draw a timeline of the relationship between an ambitious British businessman and a powerful Chinese family that has resulted in the death of one and the downfall of the other.

It began more than 15 years ago in Dalian, a large port city on China's northeast coast that was about to undergo a remarkable transformation. Today, Dalian markets itself as a green hi-tech hub and international conference centre. But then it was trying to shake off a reputation for depressed rust-belt industries and state-owned enterprises that were targeted for closure.

This was fertile ground for chancers, and in particular, for two men trying to make their mark – albeit at very different levels. Heywood was in his early 20s and had graduated from Warwick university with a degree in politics and international studies. Having odd-jobbed his way across the US and sailed the Atlantic, the Old Harrovian earned a living in China by teaching English, but took every opportunity to cultivate local officials who might further his goals to break into business.

He wrote a self-introduction to Bo, who had taken over as mayor of Dalian in 1993. Although 10 years Heywood's senior, Bo was also working his way up the Communist hierarchy, and trying to ensure his family would prosper and avoid the hardship of his youth. During the Cultural Revolution, Bo was a Maoist Red Guard, but was later imprisoned for five years and his father was tortured when the family fell out of favour.

His second wife, Gu Kailai, was the daughter of a Communist party general. Her father had also been imprisoned during the political tumult of the 1960s. She – like Bo – overcame this bitter period, went on to attend a prestigious university and became an accomplished lawyer. She was said to be the first Chinese attorney to win a legal case in the US, but this failed to silence critics who accused her of cashing in on her husband's political connections.

Perhaps seeking greater stability for their offspring, this high-profile couple wanted their son, Guagua, to study in Britain. It was here that Heywood really proved his worth, working with others to secure a place at his alma mater, Harrow. That opened the door for the Briton to enter the inner circle of Bo's family, where he – like many other foreign go-betweens – could trade on privileged connections to the Chinese Communist elite.

It was good timing. Bo was moving rapidly up the party hierarchy. In 2000, he was promoted to governor of Liaoning province. Three years later, he became minister of commerce and added to his growing international fame by negotiating a trade dispute over Italian shoes with the then EU trade commissioner, Peter Mandelson. Heywood followed him to Beijing and established a consultancy.

The Briton did not appear to have profited greatly from his business, though he earned enough to live in a villa in the north of the capital and put his children through the nearby Dulwich College Beijing. He did not have a wide social circle, but intimates spoke highly of him as a somewhat scatty, but charming individual.

"He was fantastic. He was a lovely, lovely man," said one. "He didn't have many friends – but was charming and gave people his full attention: "He was very welcoming; he really brought you in and included you."

Others saw him more as a man of mystery. "He was well-mannered and pleasant" said one, who described him as "unusually unforthcoming" as well as "studiously and almost clumsily elusive" about his work. Such behaviour has prompted speculation that he was a spy, based on his oft-expressed patriotism and less well-known work for Hakluyt & Co, a corporate intelligence consultancy established by former members of MI6. Exactly what he did for the company remains unclear. Heywood appeared to play up to the image, taking on a job for the Beijing dealership of Aston Martin – the car associated with James Bond – and driving a car with a 007 number plate.

Bo, meanwhile, was moving in a different direction. In 2007, he entered the politburo and was made party boss of Chongqing, a fast-growing municipality that was in the frontline of a multibillion-dollar project to open up western China to development. Bo turned the region into a personal fiefdom and a bully pulpit from which he publicly – and unusually, by the standards of Chinese politics – championed a shake-up of the status quo. He cracked down on organised crime in 2010 and cranked up the ideological volume with a series of mass "red song" campaigns in 2011 that filled sports stadiums with the sound of old-school Maoist choruses.

For a victim of the Cultural Revolution to steal the colours of his tormentors was an act of ruthless opportunism, twisted genius or supreme irony. There were complaints that he ran roughshod over the law, ignored party regulations and allowed his handpicked police chief, Wang Lijun, to use torture to secure confessions. But few commented publicly at the time. Bo was flying high. Inequality was falling. Investment was rising. The apparent successes of the "Chongqing model" generated such wide coverage that Bo risked outshining president Hu Jintao or his anointed successor, Xi Jinping.

But behind the populist veneer, all was not well in the family. Gu and her husband appeared increasingly distant as his political campaigns kept him in Chongqing, while her business and family concerns led her to spend more time overseas. China's increasingly assertive micro-bloggers were also asking questions about the ostentatious lifestyle of their son, Guagua, who was known for champagne parties at Balliol College in Oxford, and turned up for a date with the US ambassador's daughter in 2011 driving a red Ferrari. How, many wondered, could the family afford this?

Relations cooled some time after 2007, when Gu was targeted in a corruption investigation. Heywood told friends the lawyer had grown paranoid and demanded the members of her inner circle swear an oath of loyalty and divorce their spouses. After this, the Englishman started describing Gu as "mentally unstable" and an unforgiving "empress."

In the past year, friends said Heywood seemed stressed. "He said he was on his knees and couldn't take any more on ... I almost didn't recognise him [seeing him after a gap of a few months] – he had aged a huge amount," said one who believed Heywood was overloaded with work. By some accounts, Heywood was resigned to falling out of favour with the Bos, but remained in contact with Guagua. Another report suggested the rift was so serious that Heywood grew concerned about his safety.

Heywood's movements during the last few days of his life are one of the many outstanding mysteries in this tale. His wife, Wang Lulu – who lives in Beijing — has been told not to talk about the case. Friends and associates are reluctant to go on the record, but have suggested he was summoned to Chongqing by the Bo family – and felt trepidation about the trip – on 13 November.

According to the Times, he was accompanied by Zhang Xiaojun, a Bo loyalist who had once served as a family bodyguard – and is now reportedly detained. In Chongqing, Heywood was lodged in a private villa in the Nanshan Lijing Holiday hotel, a three-star resort amid a secluded hillside copse overlooking the city.

His body was found two days later. In a written statement to parliament this week, William Hague said British consular officials were informed on 16 November by a fax from the Chongqing police that said the businessman had died from alcohol overconsumption. With the family's agreement, the body was cremated soon afterwards without a full medical investigation into the cause of death. Friends, though, were astonished. They said Heywood rarely drank alcohol, though he "smoked like a chimney".

Was the UK government negligent? Hague left open that possibility this week by ordering an investigation into the consulate's response. It is hard to imagine UK officials were not aware of Heywood's links to Bo, the most powerful politician in the region. The Foreign Office has yet to respond to MPs' questions about whether the businessman was an informer. Even if that were not the case, demands for an investigation might have overshadowed a visit to Chongqing that week by a senior UK delegation – headed by minister of state Jeremy Browne, who met Bo on 16 November.

Suspicions continued to swirl in the British expatriate community that the death was no accident. Hague said it was not until more than two months later – 18 January – that UK officials were made aware of those rumours, but the issue was not raised with the Chinese authorities.

The story might have then faded into obscurity were it not for a stunning appearance three weeks later at the US consulate in Chengdu of Chongqing's chief of police, carrying a bag full of documents about the case and asking for protection from Bo. Wang Lijun said his life was at risk because he had discovered evidence implicating Gu Kailai in Heywood's death, the New York Times reported this week. US officials pre-empted efforts to claim asylum but reportedly kept him safe from the security forces loyal to Bo who had surrounded the consulate until a senior Chinese official from Beijing came to take him out of his former master's stronghold.

The murder allegations became impossible to ignore. On 7 February, the UK government called for an investigation. Two months later, on 10 April, the Chinese government announced the detention of Gu Kailai and Zhang Xiaojun for murder. Bo was removed from all party posts and investigated for a "serious breach of party discipline".

Since then, no evidence has come to light to prove the allegations, but a drip-feed of leaks from the authorities has strengthened public perceptions of guilt. Unnamed sources said to be close to the investigation suggest Heywood was poisoned with cyanide after quarrelling with Gu over his commission for transferring funds overseas. Whether that is the truth may never be known.

The scandal could hardly be more sensitive, coming ahead of a once-in-a-generation shift of power in China later this year. The demise of Bo – a powerful politician who was expected to enter the inner sanctum of the Communist party this year – is a gift for rivals who control news outlets and police investigations.

There is still no evidence for murder, but fresh leaks and sensational rumours emerge every day. The investigation continues. People are still being detained and the political fallout is unclear. In the meantime, China continues to be gripped by the mysterious death of an Englishman that has shed a lurid – though far from penetrating – light on an opaque political system.