How much money is there for healthcare in my country? Is more money being spent on primary or secondary schools? Is investment in agriculture going up or down? These are simple, but crucial, questions. However, for developing countries that receive foreign aid, it's notoriously difficult to get complete and up-to-date answers. Even in countries where national budgets are relatively easy to access and analyse, aid spends are all too often the crucial, missing pieces of the puzzle, creating huge headaches for governments and civil society groups eager to make sure precious resources are wisely spent.

Part of the challenge is that developing countries, on average, receive aid from an increasing number of donors. While in the past a country might receive aid from two or three, now it more likely has to deal with dozens, each with different sets of priorities and different ways of allocating and reporting aid. The knock-on effect of this confusion, according to aid transparency campaigners, is that without a clear picture of where all of these various aid flows are going, governments can't properly plan where to allocate their own resources and civil society is not given the information it needs to monitor spending and hold leaders to account.

Four years ago, researchers at the London-based Overseas Development Institute took up the enormous task of trying to figure out how dozens of donors were spending aid in Uganda, and how that compared with where the government was allocating its own resources. The results were striking: it turned out the Ugandan government was only aware of half the aid being spent in the country, despite routinely requesting this information from donors.

Also alarming was just how difficult and time-consuming it was to gather and analyse this information. Mapping donors' aid spending to a country's budget is, unfortunately, not a trivial task, even if the data is available. Donors classify and divide their spends in different ways, so researchers had to play a herculean matching game, piecing together how donors' spends fit into the bigger puzzle.

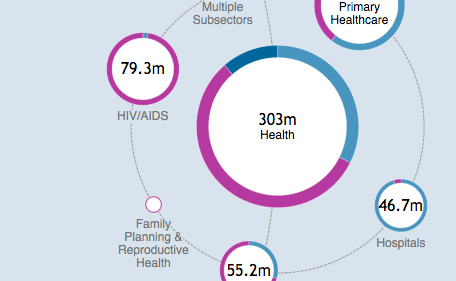

The Publish What You Fund campaign group and the Open Knowledge Foundation have now produced a visualisation of Uganda's aid and budget data for 2003-2006, billed as the first time both sets of data have been displayed together in a way that is easy to explore. A quick look shows just how big a piece of the puzzle aid spending is – more than 50% of overall resources available in Uganda for 2005-2006. The vast majority of this $1.1bn in aid was spent directly by donors on various projects, with only a third given to the government to spend along with its domestic resources. Interestingly, aid money made up only a small proportion of resources for education, while accounting for the majority of resources for health, agriculture, water and the environment.

Researchers now plan to refresh this project with more up-to-date data, but the real ambition is to be able to track aid money and government spending – and monitor their impacts – in real time. The International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), which is gathering significant momentum in advance of next week's international aid effectiveness conference in Busan, hopes to help make this process not just easier, but also more immediate. If donors publish their data to the IATI standard, the prospect is a wealth of timely aid data, both about what donors are currently spending and about what they plan to spend in the future. This, combined with the World Bank's ongoing work to create sets of codes to help match donor aid spends to domestic budget lines, should make it easier to get a fuller picture of the resources available for development in countries around the world.

While this can all sound dry and overly technical, the implications are anything but: this is the kind of aid transparency that aims to put developing countries in the driver's seat. With this information, campaigners argue, civil society will be better equipped to track down evidence of waste and corruption, and will be able to have more informed debates on how their governments are spending precious resources. "Ultimately, the aim of aid should be to remove the need for it – and this will only happen if recipient countries have information that enables them to plan and to be held to account," says Karin Christiansen, managing director of Publish What You Fund.

Critics argue that aid and budget transparency movements lack evidence that having more freely accessible spending data will make any kind of tangible difference to the world's poorest people. Five months after the Kenyan government launched its national open data initiative, only a few projects have been established to use and investigate it. Will this change over time? Or as aid data becomes more available? Who knows. But while sceptics can continue to pick away at these efforts, they have yet to come up with a convincing case for keeping the books closed.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion