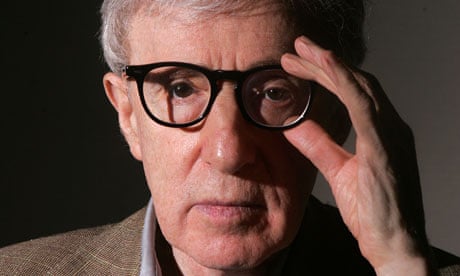

He may have written, directed and starred in several films that others consider to be comic masterpieces, but Woody Allen believes none of them will stand the test of time, according to a new documentary.

Referring to his four-decade career, Allen – whose latest film, Midnight in Paris, is unveiled at the Cannes film festival – admitted that endurance was "an achievement of sorts, but not the one that I care about".

"It's a secondary achievement," said the director of Annie Hall. "But to make a fine film, that's a different story. That has eluded me over the decades."

The documentary has been made by Oscar-nominated film-maker Robert Weide, whose earlier subjects have included the Marx Brothers. It took more than 20 years to persuade Allen to agree, but in the end he was given unprecedented access over 18 months.

"Woody's harshest critic is himself," Weide said. "He's the one who says he's never made a great film. I said: 'What about … Annie Hall, Manhattan, Hannah and Her Sisters or Crimes and Misdemeanors?' He said: 'Those films came out OK, but they're not great films; they won't stand the test of time like [Vittorio De Sica's] Bicycle Thieves or [Jean Renoir's] La Grande Illusion.' He's always grading on that sort of scale."

That self-criticism is made clear in the documentary, which Weide expects to be screened on both sides of the Atlantic later this year. Speaking of Manhattan, an enduring classic loved by legions of fans, Allen said he was so disappointed by the result that he begged the studio to ditch it. "I didn't like the film at all … I spoke to United Artists at the time and offered to make a film for them for nothing if they would not put it out," he said.

Allen, 75, exudes the self-deprecating humour in the documentary that audiences adore in his screen characters. "I've contributed my share of mediocre and very bad films, just like everybody else," he told Weide. "I've been working on the quantity theory. I feel if I keep making films, every once in a while I'll get lucky and one will come out OK. And that's exactly what happens."

Weide said he was astonished to be allowed to film Allen at work, as the set has always been off limits until now. "The accepted wisdom about Woody is that he is a minimalist director … [But] Woody's thing is always that if an actor wants direction from him, he'll give it. As he said to me, 'if they ask me a question, I'm not going to stare at them until they walk away. I'll respond'," he said.

Allen also allowed himself to be filmed at home, lying on his bed, writing a draft script in longhand before typing it out on the manual typewriter he has used for all his work since he was a teenager.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion