Anemia

(redirected from Addison-Biermer anemia)Also found in: Dictionary, Thesaurus, Encyclopedia.

anemia

[ah-ne´me-ah]

Some types of anemia are named for the factors causing them: poor diet (nutritional anemia), excessive blood loss (hemorrhagic anemia), congenital defects of hemoglobin (hypochromic anemia), exposure to industrial poisons, diseases of the bone marrow (aplastic anemia and hypoplastic anemia), or any other disorder that upsets the balance between blood loss through bleeding or destruction of blood cells and production of blood cells. Anemias can also be classified according to the morphologic characteristics of the erythrocytes, such as size (microcytic, macrocytic, and normocytic anemias) and color or hemoglobin concentration (hypochromic anemia). A type called hypochromic microcytic anemia is characterized by very small erythrocytes that have low hemoglobin concentration and hence poor coloration. Data used to identify anemia types include the erythrocyte indices: (1) mean corpuscular volume (MCV), the average erythrocyte volume; (2) mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), the average amount of hemoglobin per erythrocyte; and (3) mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), the average concentration of hemoglobin in erythrocytes. adj., adj ane´mic.

Dietary Deficiencies and Abnormalities of Red Blood Cell Production (Nutritional Anemia, Aplastic Anemia, and Hypoplastic Anemia): Anemia may develop if the diet does not provide enough iron, protein, vitamin B12, and other vitamins and minerals needed in the production of hemoglobin and the formation of erythrocytes. The combination of poor diet and chronic loss of blood makes for particular susceptibility to severe anemia. Anemias associated with folic acid deficiency are very common.

Excessive Destruction of Red Blood Cells (hemolytic anemia): Anemia may also develop related to hemolysis due to trauma, chemical agents or medications (toxic hemolytic anemia), infectious disease, isoimmune hemolytic reactions, autoimmune disorders, and the paroxysmal hemoglobinurias.

Activity intolerance is a common problem for patients with anemia. Physical activity increases demand for oxygen, but if there are not enough circulating erythrocytes to provide sufficient oxygen, patients become physically weak and unable to engage in normal physical activity without experiencing profound fatigue. This can result in some degree of self-care deficit as the fatigue interferes with the patient's ability to carry on regular or enjoyable activities.

Immune complex problems: Ingestion of any of a large number of drugs is followed by immunization and the formation of a soluble drug–anti-drug complex that adsorbs nonspecifically to the erythrocyte surface.

Drug absorption: Drugs bind firmly to erythrocyte membrane proteins, inducing the formation of specific antibodies; the drug most commonly associated with this mechanism is penicillin.

Membrane modification: A nonimmunologic mechanism whereby the drug involved is able to modify erythrocytes so that plasma proteins can bind to the membrane.

Autoantibody formation: Methyldopa (Aldomet) induces the production of autoantibodies that recognize erythrocyte antigens and are serologically indistinguishable from those seen in patients with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

a·ne·mi·a

(ă-nē'mē-ă),anemia

alsoanaemia

(ə-nē′mē-ə)anaemia

A condition characterised by decreased red cells or haemoglobin in the blood, resulting in decreased O2 in peripheral tissues. Anaemias are divided into various groups based on cause—e.g., iron deficiency anaemia, megaloblastic anaemia (due to decreased vitamin B12 or folic acid) or aplastic anaemia (where RBC precursors in the bone marrow are depleted).Clinical findings

Fatigability, pallor, palpitations, shortness of breath.

Anaemia classifications

Morphology

Macrocytic

• Megaloblastic anaemia:

– Vitamin B12 deficiency;

– Folic acid deficiency.

Microcytic hypochromic

• Iron-deficiency anaemia;

• Hereditary defects;

• Sickle cell anaemia;

• Thalassemia;

• Other heamoglobinopathies.

Normocytic

• Acute blood loss;

• Haemolysis;

• BM failure;

• Anaemia of chronic disease;

• Renal failure.

Aetiology

Deficiency

• Iron;

• Vitamin B12;

• Folic acid;

• Pyridoxine;

Central (due to BM failure)

• Anaemia of chronic disease;

• Anaemia of senescence;

• Malignancy:

– BM replacement by tumour;

– Toxicity due to chemotherapy;

– Primary BM malignancy, e.g., leukaemia.

Peripheral

• Haemorrhage;

• Haemolysis.

anemia

Hematology A condition characterized by ↓ RBCs or Hb in the blood, resulting in ↓ O2 in peripheral tissues Clinical Fatigability, pallor, palpitations, SOB; anemias are divided into various groups based on cause–eg, iron deficiency anemia, megaloblastic anemia–due to ↓ vitamin B12 or folic acid, or aplastic anemia–where RBC precursors in BM are 'wiped out'. See Anemia of chronic disease, Anemia of investigation, Anemia of prematurity, Aplastic anemia, Arctic anemia, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Cloverleaf anemia, Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia, Dilutional anemia, Dimorphic anemia, Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia, Fanconi anemia, Hemolytic anemia, Idiopathic sideroblastic anemia, Immune anemia, Iron-deficiency anemia, Juvenile pernicious anemia, Macrocytic anemia, Megaloblastic anemia, Microcytic anemia, Myelophthisic anemia, Neutropenic colitis with aplastic anemia, Nonimmune hemolytic anemia, Pseudoanemia, Refractory anemia with excess blasts, Sickle cell anemia, Sideroblastic anemia, Sports anemia.General groups of anemia

- Morphology

- Macrocytic

- Megaloblastic anemia

- Vitamin B12deficiency

- Folic acid deficiency

- Microcytic hypochromic

-

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Hereditary defects

- Sickle cell anemia

- Thalassemia

- Other hemoglobinopathies

- Normocytic

-

- Acute blood loss

- Hemolysis

- BM failure

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Renal failure

- Etiology

- Deficiency

-

- Iron

- Vitamin B12

- Folic acid

- Pyridoxine

- Central–due to BM failure

-

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Anemia of senescence

- Malignancy

- BM replacement by tumor

- Toxicity due to chemotherapy

- Primary BM malignancy, eg leukemia

- Peripheral

-

- Hemorrhage

- Hemolysis

a·ne·mi·a

(ă-nē'mē-ă)Synonym(s): anaemia.

anemia

(a-ne'me-a) [ ¹an- + -emia]Symptomatic anemia exists when hemoglobin content is less than that required to meet the oxygen-carrying demands of the body. If anemia develops slowly, however, there may be no functional impairment even though the hemoglobin is less than 7 g/100/dL of blood.

Anemia is not a disease but rather a symptom of other illnesses. It is classified on the basis of mean corpuscular volume as microcytic (80), normocytic (80–94), and macrocytic (> 94); on the basis of mean corpuscular hemoglobin as hypochromic (27), normochromic (27–32), and hyperchromic (> 32); and on the basis of etiological factors.

Etiology

Anemia may be caused by bleeding, e.g., from the gastrointestinal tract or the uterus; vitamin or mineral deficiencies, esp. vitamin B12, folate, or iron; decreases in red blood cell production, e.g., bone marrow suppression in kidney failure or bone marrow failure in myelodysplastic syndromes; increases in red blood cell destruction as in hemolysis due to sickle cell anemia; or increases in red blood cell sequestration by the spleen (as in portal hypertension), or administration of toxic drugs (as in cancer chemotherapy).

Symptoms

Anemic patients may experience weakness, fatigue, lightheadedness, breathlessness, palpitations, angina pectoris, and headache. Signs of anemia may include a rapid pulse or rapid breathing if blood loss occurs rapidly. The chronically anemic may have pale skin, mucous membranes, or nail beds and fissures at the corners of the mouth.

Treatment

Treatment of anemia must be specific for the cause. The prognosis for recovery from anemia is excellent if the underlying cause is treatable.

Anemia due to excessive blood loss: For acute blood loss, immediate measures should be taken to stop the bleeding, to restore blood volume by transfusion, and to combat shock. Chronic blood loss usually produces iron-deficiency anemia.

Anemia due to excessive blood cell destruction: The specific hemolytic disorder should be treated.

Anemia due to decreased blood cell formation: For deficiency states, replacement therapy is used to combat the specific deficiency, e.g., iron, vitamin B12, folic acid, ascorbic acid. For bone marrow disorders, if anemia is due to a toxic state, removal of the toxic agent may result in spontaneous recovery.

Anemia due to renal failure, cancer chemotherapy, HIV, and other chronic diseases: Erythropoietin injections are helpful.

Patient care

The patient is evaluated for signs and symptoms, and the results of laboratory studies are reviewed for evidence of inadequate erythropoiesis or premature erythrocyte destruction. Prescribed diagnostic studies are scheduled and carried out. Rest: The patient is evaluated for fatigue; care and activities are planned and regular rest periods are scheduled. Mouth care: The patient's mouth is inspected daily for glossitis, mouth lesions, or ulcers. A sponge stick is recommended for oral care, and alkaline mouthwashes are suggested if mouth ulcers are present. A dental consultation may be required. Diet: The patient is encouraged to eat small portions at frequent intervals. Mouth care is provided before meals. The nurse or a nutritionist provides counseling based on type of anemia. Medications: Health care professionals teach the patient about medication actions, desired effects, adverse reactions, and correct dosing and administration. Patient education: The cause of the anemia and the rationale for prescribed treatment are explained to the patient and family. Teaching should cover the prescribed rest and activity regimen, diet, prevention of infection, including the need for frequent temperature checks, and the continuing need for periodic blood testing and medical evaluation.

achlorhydric anemia

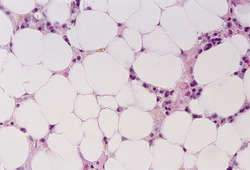

aplastic anemia

Treatment

Many patients can be treated effectively with bone marrow transplantation or immunosuppressive drugs.

Patient care

The patient and family are educated about the cause and treatment of the illness. Measures to prevent infection are explained, and the importance of adequate rest is emphasized. In the acute phase, prescribed treatment is carried out; side effects of drugs and transfusions are explained, and a restful environment for the patient is ensured. If the patient's platelet count is low (less than 20,000/cu mm), the following steps are taken to prevent hemorrhage: avoiding parenteral injections, suggesting the use of an electric razor, use of humidifying oxygen to prevent dry mucous membranes, and promoting regular bowel movements with stool softeners and dietary measures. Pressure is applied to all venipuncture sites until bleeding has stopped, and bleeding is detected early by checking for occult blood in urine and stools and by assessing the skin for petechiae and ecchymoses. Standard precautions and careful handwashing (and protective isolation if necessary) are used; a diet high in vitamins and protein is provided, and meticulous oral and perianal care are provided. The patient is assessed for life-threatening hemorrhage, infection, adverse effects of drug therapy, or blood transfusion reactions. Throat, urine, and blood cultures are performed when indicated to identify infection. See: protective isolation

autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Abbreviation: AIHAanemia of chronic inflammation

Inflammatory anemia.congenital hemolytic anemia

congenital hypoplastic anemia

Diamond-Blackfan anemia.Cooley anemia

See: Cooley anemiadeficiency anemia

Diamond-Blackfan anemia

See: Diamond-Blackfan anemiaerythroblastic anemia

folic acid deficiency anemia

Patient care

Fluid and electrolyte balance is monitored, particularly in the patient with severe diarrhea. The patient can obtain daily folic acid requirements by including an item from each food group in every meal; a list of foods rich in folic acid (green leafy vegetables, asparagus, broccoli, liver and other organ meats, milk, eggs, yeast, wheat germ, kidney beans, beef, potatoes, dried peas and beans, whole-grain cereals, nuts, bananas, cantaloupe, lemons, and strawberries) is provided. The rationale for replacement therapy is explained, and the patient is advised not to stop treatment until test results return to normal. Periods of rest and correct oral hygiene are encouraged.

hemolytic anemia

hyperchromic anemia

hypochromic anemia

hypoplastic anemia

inflammatory anemia

iron-deficiency anemia

Abbreviation: IDAEtiology

IDA is caused by inadequate iron intake, malabsorption of iron, blood loss, pregnancy and lactation, intravascular hemolysis, or a combination of these factors.

Symptoms

Chronically anemic patients often complain of fatigue and dyspnea on exertion. Iron deficiency resulting from rapid bleeding, may produce palpitations, orthostatic dizziness, or syncope.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies reveal decreased iron levels in the blood, with elevated iron-binding capacity and a diminished transferrin saturation. Ferritin levels are low. The bone marrow does not show stainable iron.

Additional Diagnostic Studies

Adult nonmenstruating patients with IDA should be evaluated to rule out a source of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract.

Treatment

Dietary iron intake is supplemented with oral ferrous sulfate or ferrous gluconate (with vitamin C to increase iron absorption). Oral liquid iron supplements should be given through a straw to prevent staining of the teeth. Iron preparations cause constipation; laxatives or stool softeners should be considered as concomitant treatment. When underlying lesions are found in the gastrointestinal tract, e.g., ulcers, esophagitis, cancer of the colon, they are treated with medications, endoscopy, or surgery.

CAUTION!

Parents should be warned to keep iron preparations away from children because three or four tablets may cause serious poisoning.macrocytic anemia

Mediterranean anemia

See: thalassemiamegaloblastic anemia

microcytic anemia

milk anemia

anemia of the newborn

normochromic anemia

normocytic anemia

nutritional anemia

Deficiency anemia.pernicious anemia

Etiology

Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune disease. The parietal cells of the stomach lining fail to secrete enough intrinsic factor to ensure intestinal absorption of vitamin B12, the extrinsic factor. This is the result of atrophy of the glandular mucosa of the fundus of the stomach and is associated with absence of hydrochloric acid.

Symptoms

Symptoms include weakness, sore tongue, paresthesias (tingling and numbness) of the extremities, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and pain; in severe anemia, there may be signs of cardiac failure.

Treatment

Vitamin B12 is given parenterally or, in patients who respond, intranasally or orally.

physiological anemia of pregnancy

anemia of prematurity

runner's anemia

septic anemia

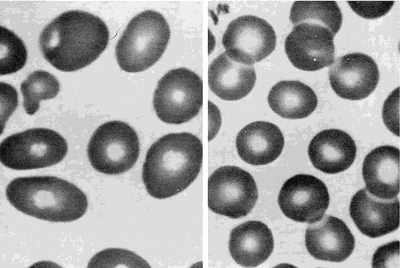

sickle cell anemia

Etiology

When both parental genes carry the same defect, the person is homozygous for hemoglobin S, i.e., HbSS, and manifests the disorder. When exposed to a decrease in oxygen, hemoglobin S becomes viscous. This causes the red cells to become crescent-shaped (sickled), rigid, sticky, and fragile, increasing red-cell destruction (hemolysis). When sickled red blood cells clump together, circulation through the capillaries is impeded, causing obstruction, tissue hypoxia, and further sickling. In infants younger than 5 months old, high levels of fetal hemoglobin inhibit the reaction of the hemoglobin S molecule to decreased oxygen.

Symptoms

The shortened life span of the abnormal red cells (10–20 days) results in a chronic anemia; pallor, weakness, and fatigue are common. Jaundice may result from hemolysis of red cells. Crisis may occur as a result of sickling, thrombi formation, vascular occlusion, tissue hypoxia, and infarction. People with sickle cell anemia are at increased risk of bacterial infections relative to the general population. Specific risks include osteomyelitis, meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis from agents such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia. Sickle cell patients with fever, cough, and/or regional pain should begin antibiotic therapy immediately after cultures for blood and urine and diagnostic x-rays are obtained. Sickle cell anemia also increases the risk for ischemic organ and tissue damage. Intensely painful episodes (crises) affecting the extremities, back, chest, and abdomen can last from hours to weeks and are the most frequent cause of hospitalization. Crises can be triggered by hypoxemia, infection, dehydration, and worsening anemia. Sickle cell crisis should be suspected in the sickle cell patient with pale lips, tongue, palms, or nail beds; lethargy; listlessness; difficulty awakening; irritability; severe pain; or temperature over 104°F (37.8°C) lasting at least 2 days. Life-threatening complications may arise from damage to specific internal organs, including splenic infarcts, myocardial infarction, acute chest syndrome, liver injury, aplastic anemia, and multiorgan dysfunction syndrome. See: sickle cell crisis

Treatment

Supportive therapy includes supplemental iron and blood transfusion. Administration of hydroxyurea stimulates the production of hemoglobin F and decreases the need for blood transfusions and painful crises. Prophylactic daily doses of penicillin have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the incidence of acute bacterial infections in children. Life-threatening complications require aggressive transfusion therapy or exchange transfusion, hydration, oxygen therapy, and the administration of high doses of pain relievers. Bone marrow transplantation, when a matched donor is available, can cure sickle cell anemia.

Patient care

During a crisis, patients are often admitted to the hospital to treat pain and stop the sickling process. Adequate pain control is vital. Morphine is the opioid of choice to manage pain because it has flexible dosing forms, proven effectiveness, and predictable side effects. It should be administered using patient-controlled analgesia, continuous low-dose intravenous infusions, or sustained release pain relievers to maintain consistent blood levels. Supplemental short-acting analgesics may be needed for breakthrough pain. Side effects of narcotic pain relievers should be treated with concurrent administration of antihistamines, antiemetics, stool softeners, or laxatives. When administering pain relievers, care providers should assess pain using a visual analog scale to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment. Other standard pain reduction techniques, such as keeping patients warm, applying warm compresses to painful areas, and keeping patients properly positioned, relaxed, or distracted may be helpful. Patients and families are to be advised never to use cold applications for pain relief because this treatment aggravates sickling. If transfusions are required, packed red blood cells (leukocyte-depleted and matched for minor antigens) are administered, and the patient is monitored for transfusion reactions. Scheduled deep breathing exercises or incentive spirometry helps to prevent atelectasis, pneumonia, and acute chest syndrome. During remission, the patient can prevent some exacerbations with regular medical checkups; the use of medications such as hydroxyurea; consideration of bone marrow transplantation; avoiding hypoxia (as in aircraft or at high altitudes); excessive exercise; dehydration; vasoconstricting drugs; and exposure to severe cold. The child must avoid restrictive clothing, strenuous exercise and body-contact sports but can still enjoy most activities. Additional fluid should be consumed in hot weather to help prevent dehydration. Patients and families should be advised to seek care at the onset of fevers or symptoms suggestive of infectious diseases. Annual influenza vaccination and periodic pneumococcal vaccination may prevent these common infectious diseases. Affected families should be referred for genetic counseling regarding risks to future children and for psychological counseling related to feelings of guilt. Screening of asymptomatic family members may determine whether some are heterozygous carriers of the sickling gene. Families affected by sickle cell anemia may gain considerable support in their communities or from national associations such as the American Sickle Cell Anemia Association, www.ascaa.org.

splenic anemia

transfusion-dependent anemia

CAUTION!

Iron overload may be a complication of therapy, esp. after the transfusion of over 10 units of blood.Anemia

a·ne·mi·a

(ă-nē'mē-ă)Synonym(s): anaemia.

Patient discussion about Anemia

Q. What is the Treatment for Anemia? I would like to know what are the possible treatments for anemia?

Q. What are the Symptoms of Anemia? Lately I've been feeling very tired. My friend suggested I might be anemic. What are the major symptoms of anemia?

The body also has a remarkable ability to compensate for early anemia. If your anemia is mild or developed over a long period of time, you may not notice any symptoms. Symptoms common to many types of anemia include the following:

Easy fatigue and loss of energy

Unusually rapid heart beat, particularly with exercise

Shortness of breath and headache, particularly with exercise

Difficulty concentrating

Dizziness

Pale skin

Leg cramps

Insomnia

Hope this helps.

http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/understanding-anemia-symptoms

Q. What is the Definition of Anemia? My doctor told me I have anemia, based on my latest blood tests. What is anemia?