Twenty years ago today, the organization that created the World Wide Web made its underlying technology available to everyone on a royalty-free basis. To commemorate that occasion, the very first website is now back online at its original URL.

Physicist Tim Berners-Lee invented the Web in 1989 at CERN, the European nuclear research and particle physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland. CERN didn't try to keep the technology to itself. The Web became publicly accessible on Aug. 6, 1991, and "[o]n 30 April 1993 CERN published a statement that made World Wide Web ('W3', or simply 'the web') technology available on a royalty-free basis," the organization wrote today. "By making the software required to run a web server freely available, along with a basic browser and a library of code, the web was allowed to flourish."

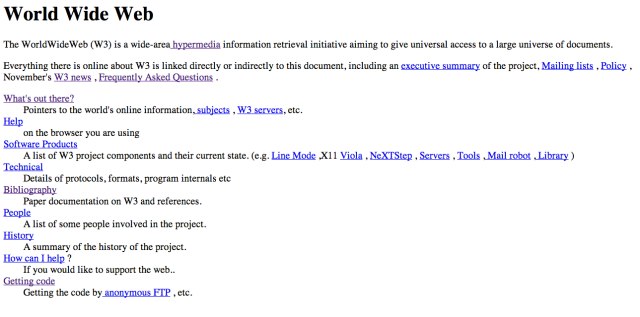

Snapshots of the original website were preserved, but not the site itself at its original URL, until now. "Although the NeXT machine—the original web server—is still at CERN, sadly the world's first website is no longer online at its original address," CERN wrote. CERN is now fixing that oversight, with the first site back online at http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html. Previously, that URL simply redirected to http://info.cern.ch. Here's what it looks like now:

The website describes what the Web actually is, and it points to further pages describing the history of the project and how Web technology works.

CERN's restoration project will go beyond simply preserving the website. "For a start we would like to restore the first URL—put back the files that were there at their earliest possible iterations," the first website project site notes. "Then we will look at the first web servers at CERN and see what assets from them we can preserve and share. We will also sift through documentation and try to restore machine names and IP addresses to their original state. Beyond this we want to make http://info.cern.ch—the first web address—a destination that reflects the story of the beginnings of the web for the benefit of future generations."

Berners-Lee hosted the first website on a computer built by NeXT, the company Steve Jobs founded when he was exiled from Apple. That very first Web server does still exist, and it recently got a tune-up.

"We have made a check-up of the NeXT, removed the dust, changed the lithium battery of the RTC and made a backup of the hard drive," a CERN blog post states. "The data of the hard drive have been written on a bootable linux CD-ROM."

The first website you can view today is actually a 1992 copy. A project blog post promises that CERN will keep looking for earlier ones, but for now what you see may not be exactly what the site looked like when it first launched. One commenter on that blog post summed up the problems in preserving digital bits of human history, writing, "Great stuff. It's crazy that 48 copies of the 600 year-old Gutenberg bible exist, yet not one copy of a website made just twenty-odd years ago survives. History will look back at us and roll its eyes."

How the Web became free and open

Vint Cerf, co-creator of the TCP/IP protocols and architecture that power the Internet, shared his thoughts on the open Web's 20th anniversary, noting that "[t]he WWW design, like the design of the internet, was very open and encouraged a growing cadre of self-taught webmasters to develop content and applications." The Web's openness has "meant that parts of the internet could attack other parts," Cerf wrote. "There is still a great deal of technical and policy work to be done to protect users, network and application service providers from harm."

So just how did the Web become the open network we know and love today? Robert Cailliau, who collaborated with Tim Berners-Lee in building the World Wide Web at CERN, explains that making the Web's technology public property was not a complete no-brainer:

We had a few more serious brainstorming sessions about the status of WWW, but in the end a few things became clear: what we had was not a patentable, slick "App", we had standards (html, http) and a few pieces of software that used them, but nothing shining. There were also a fair number of highly developed content networks already in operation, several in the US, several in Europe. We would be competing with those, and doing it on a platform called the internet, that nobody outside academia had heard much about.

Broadly speaking the big choice was between putting WWW in the public domain and keeping it as CERN's intellectual property.

It took some time to decide what to do, because the arguments were complex, the models untried, and it was not clear what would happen to WWW in either case. Finally, as we were more interested in the excitement of making something useful than in getting rich, we opted for using the old CERN model for technology spin-off: make it available.

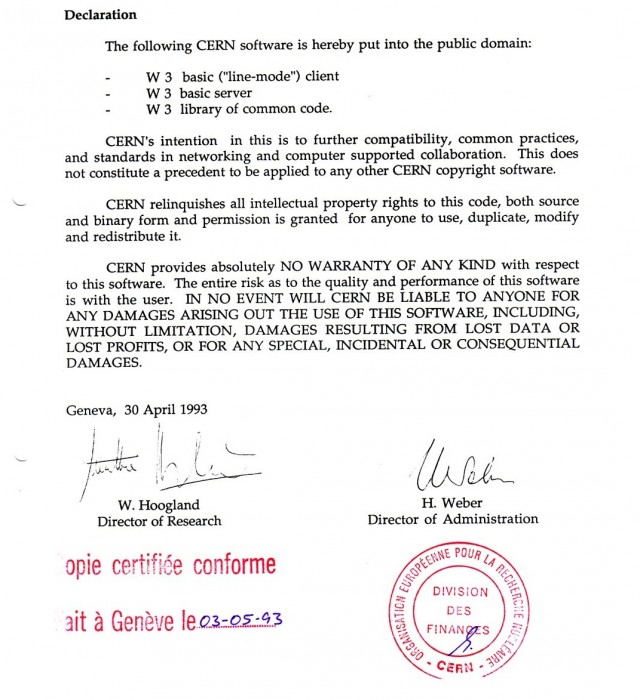

Making the decision official required about six months of back-and-forth with CERN's legal team. "The Legal Service worked hard on this, because they had no experience with this type of situation, they had to study quite a number of similar cases from outside CERN," Cailliau wrote. "The whole thing was also complicated by the fact that CERN is not one country's institute, it belongs to 20 individual member states. I also had to ensure that the document was endorsed by the CERN management and signed by at least two directors."

The final document stated that "CERN relinquishes all intellectual property rights to this code, both source and binary form and permission is granted for anyone to use, duplicate, modify and redistribute it."

As Cailliau writes, "A solid, simple document was signed on 30 April 1993, and the rest is history."

reader comments

116