Practice Essentials

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant syndrome as a result of defective mismatch repair (MMR) proteins. HNPCC, accounts for 2-5% of all colorectal carcinomas. Over 90% of all colorectal cancers in HNPCC patients demonstrate a high microsatellite instability (MSI-H), which means at least two or more genes have been mutated in HNPCC families or atypical HNPCC families.

Colorectal cancer in patients with HNPCC presents at an earlier age than in the general population and is characterized by an increased risk of other cancers, such as endometrial cancer and, to a lesser extent, cancers of the ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, pancreas, upper urinary tract, prostrate, brain, and skin.

HNPCC is divided into Lynch syndrome I (familial colon cancer) and Lynch syndrome II (HNPCC associated with other cancers of the gastrointestinal [GI] or reproductive system). The increased cancer risk is due to inherited mutations that degrade the self-repair capability of DNA.

The tumor testing (ie, immunohistochemistry, MSI, germline testing, and BRAF mutation testing), screening, and prophylactic surgery all help to reduce the risk of death in patients with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome.

The benefits of all strategies primarily affect relatives with a mutation associated with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome.

The widespread implementation of colorectal tumor testing helps to identify families with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome.

Colorectal tumor testing could yield substantial benefits at acceptable cost. Particularly in females with a mutation associated with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome who begin regular screening and have reducing surgery. The cost-effectiveness of such testing depends on a particular rate in relatives at risk for HNPCC or Lynch syndrome.

Background

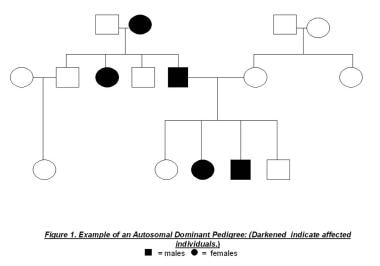

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant syndrome (see the image below), as a result of defective mismatch repair (MMR) proteins. HNPCC accounts for 2-5% of all colorectal carcinomas. Over 90% of all colorectal cancers in HNPCC patients demonstrate a high microsatellite instability (MSI-H), which means at least two or more genes have been mutated in HNPCC families or atypical HNPCC families.

See Colorectal Cancer: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Options, a Critical Images slideshow, to help identify the features several types of colorectal cancers.

Colorectal cancer in patients with HNPCC presents at an earlier age than in the general population and is characterized by an increased risk of other cancers, such as endometrial cancer and, to a lesser extent, cancers of the ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, pancreas, upper urinary tract, prostrate, brain, and skin.

HNPCC is divided into Lynch syndrome I (familial colon cancer) and Lynch syndrome II (HNPCC associated with other cancers of the gastrointestinal [GI] or reproductive system). The increased cancer risk is due to inherited mutations that degrade the self-repair capability of DNA.

Lynch syndrome was named after Dr. Henry T. Lynch. In 1966, Dr. Lynch and colleagues described familial aggregation of colorectal cancer with stomach and endometrial tumors in two extended kindreds and named it cancer family syndrome. The authors later termed this constellation Lynch syndrome, and, more recently, this condition has been called HNPCC.

Before molecular genetic diagnostics became available in the 1990s, a comprehensive family history was the only basis from which to estimate the familial risk of colorectal cancer.

Pathophysiology

In hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), an inherited mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes appears to be a critical factor. MMR genes normally produce proteins that identify and correct sequence mismatches that may occur during DNA replication. In HNPCC, a mutation that inactivates an MMR gene leads to the accumulation of cell mutations and greatly increases the likelihood of malignant transformation and cancer.

Researchers have identified seven distinct MMR genes, including the following:

-

hMLH1 on band 3p22

-

hMSH2 and hMSH6 on band 2p16

-

hPMS1 on band 3p32 and hPMS2 on band 7q22

Other mutations include hMSH3 on band 5q14.1 and EXO1 on band 1q43. Mutations of hMLH1 and hMSH2 account for nearly 70% of MMR mutations in HNPCC; 10% involve hMSH6. The genes responsible for the remaining 20-25% of cases have not yet been discovered.

Table 1. Seven different genes are known to be associated with HNPCC, and all of them are involved with DNA mismatch repair, identified with the frequencies below. (Open Table in a new window)

Mismatch Excision Repaired MMR |

Chromosome Location |

Frequency of HNPCC Cases |

MSH2 |

2p16 |

45-50% |

MLH1 |

3p22.3/A> |

20% |

MSH6 |

2p16 |

10% |

PMS2 |

7p22.1 |

1% |

PMS1 |

2q32.2 |

Rare |

MSH3 |

5q14.1 |

Rare |

EXO1 |

1q43 |

Rare |

Other genes not yet discovered |

|

20-25% |

Germline mutations are often inherited but may also arise spontaneously or de novo in a new generation. These patients are often identified only after they develop colon cancer early in life. Transmission is autosomal dominant (see image below), meaning that 50% of the offspring of affected individuals inherit a mutant allele.

Because phenotypic expression of HNPCC requires inactivation of both alleles, germline mutations of one allele must be accompanied by somatic inactivation of the wild-type allele. Inactivation may result from deletions, mutations, or splicing errors occurring anywhere throughout the gene. Mutations that lead to protein truncation account for most inactivating hMLH1 and hMSH2 mutations. Failure to correct replication errors results in genomic instability.

Despite the absence of polyposis, HNPCC-associated colorectal cancers are believed to arise from preexisting discrete proximal colonic adenomas. Affected individuals have a propensity to develop predominantly right-sided, flat adenomas at a young age. Patients with Lynch syndrome or HNPCC develop adenomas at the same rate as individuals in the general population; however, the adenomas in those with Lynch syndrome or HNPCC are more likely to progress to cancer. Carcinogenesis progresses more rapidly in these patients (in 2-3 y) than in patients with sporadic adenomas (8-10 y).

Synchronous colorectal tumors (primary tumors diagnosed within 6 mo of each other) and metachronous colorectal tumors (primary tumors occurring more than 6 mo apart) are more common in persons with HNPCC. An individual with an HNPCC mutation who does not undergo a partial or total colectomy after the first mass is diagnosed as malignant has an estimated 30-40% risk of developing a metachronous tumor within 10 years and a 50% risk within 15 years. In the general population, the risk is 3% in 10 years and 5% within 15 years.

Epidemiology

United States data

The incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) in the United States is 2-5%, or 7500 new occurrences of HNPCC annually.

International data

Large geographic differences are observed in the occurrence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

Age-related demographics

Colorectal cancer in persons with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) occurs at an earlier age than in the general population. In persons with HNPCC, the average age of polyp onset is in the late second decade and early third decade of life. The average age of colorectal cancer onset is 44 years in members of families that meet the Amsterdam criteria compared with age 60-65 years in the general population (see History, Guidelines).

Race-related demographics

Lynch syndrome has no known racial proclivity; however, ethnic-specific mutations have been observed in the Finnish and Swedish populations. Colorectal cancer rates in the Ashkenazi Jewish population are disproportionately high, possibly the highest of any ethnic group worldwide. Although neither hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) nor classic FAP are more common in Ashkenazim than in the general population, both have a connection to individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

A specific mutation in the MSH2 gene, G1906K, is found in 2-3% of all colorectal cancers in Ashkenazi Jews younger than 60 years. One third of Ashkenazi Jewish individuals who meet the criteria for genetic testing of HNPCC have this mutation. This mutation is rarely found in the general population but is more common in young Ashkenazi Jews with colorectal cancer. In individuals in whom colorectal cancer is diagnosed at age 40 years or younger, 7% have been found to carry this mutation. Conversely, the mutation is found in less than 1% of Ashkenazim persons in whom colorectal cancer is diagnosed after age 60 years.

Contrary to American and European reports, gastric cancer may be more common than endometrial cancer in the Asian (Japanese, Korean, Chinese) population.

Sex-related demographics

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is commonly diagnosed in both men and women.

Prognosis

The 5-year survival rate in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is estimated to be approximately 60%, compared with 40-50% for sporadic cases. Colorectal tumors that are microsatellite instability (MSI)-positive have distinctive features, including a tendency to arise in the proximal colon, lymphocytic infiltrated, and a poorly differentiated, mucinous or signet ring appearance. [1] Investigators have found that MSI-positive tumors are associated with improved survival rates. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

When compared based on stage, patients with colorectal cancer from families with a history of HNPCC have a better prognosis than patients with colorectal cancer in the general population (sporadic colon cancer), which may be explained by immunologic factors. Immunologic studies in mice with colon cancer have demonstrated that tumors influence host immune response by altering host T-cell receptors. [7] However, the defective T-cell response was observed only in animals with long-standing tumors, implying that rapid tumor growth, as seen in HNPCC, may preserve immune response. [7] This hypothesis merits further investigation.

The best evidence that colonoscopic screening is beneficial for preventing colon cancer in patients with HNPCC has come from observational studies of 22 HNPCC families that were followed for 15 years. [8, 9] One hundred and thirty-three family members were voluntarily screened every 3 years, and 119 declined colonoscopic surveillance during the study period.

Colorectal cancer was reduced by 62% in the screened group versus the unscreened group. The reduction was ascribed to polypectomies in the intervention group. No colorectal cancer-related deaths occurred in the group that underwent regular colonoscopic screening compared with a 36% colorectal cancer-related mortality rate in the unscreened group.

Colon cancers that occur in patients with HNPCC are believed to arise from adenomas; however, these adenomatous polyps likely have a shortened adenoma-carcinoma progression sequence compared with the general population. Thus, for a known MLH1 or MSH2 germline mutation carrier, a full colonoscopy every 1-2 years beginning at ages 20-25 years or 5 years before the first diagnosed colorectal cancer in the family is recommended. After the age of 35-40 years, colonoscopy should be performed annually.

The implementation of colorectal tumor testing to identify families with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome could yield substantial benefits at acceptable cost, particularly in females with a mutation associated with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome who begin regular screening and have prophylactic surgery. The cost-effectiveness of such testing depends on a particular rate among relatives at risk for HNPCC or Lynch syndrome. [10]

Morbidity/mortality

Although not everyone who inherits the gene for HNPCC develops colorectal cancer, individuals with Lynch syndrome have a 70-80% lifetime risk of developing colon cancer. Of these cancers, two thirds occur in the proximal colon (proximal to the splenic flexure). In approximately 45% of affected individuals, multiple synchronous and metachronous colorectal may occur within 10 years of resection.

Other cancers associated with HNPCC include the following:

-

Endometrial cancer: The lifetime risk is 30-40% by age 70 years. The average age at diagnosis is 46 years. Half of the patients with both colon and endometrial cancer present with endometrial cancer first.

-

Ovarian cancer: The lifetime risk is 9-12% by age 70 years. The average age at diagnosis is 42.5 years. Approximately 30% of these tumors present before age 40 years.

-

Gastric cancer: The lifetime risk is around 13% (higher in Asians). The mean age at diagnosis of gastric cancer is 56 years; intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is the most commonly reported pathology, especially in Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, and China.

-

Transitional cell carcinoma: The lifetime risk is 4-10%. This principally affects the upper urinary tract (ureters and renal pelvis). Certain group of patients (eg, those with HNPCC with MSH2 mutations) are at an increased risk not only for upper urinary tract tumors but also for bladder cancer.

-

Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: The lifetime risk is 1-3%. These occur most commonly in the duodenum and jejunum.

-

Glioblastoma: The lifetime risk is 1-4%. Also known as Turcot syndrome, this is a variant of HNPCC (see below).

-

Malignancies of the larynx, breast, prostate, liver, biliary tree, pancreas, and the hematopoietic system are more common in patients with HNPCC.

Table 2. Incidence of different types of cancers in individuals with Lynch syndrome and those in the general population. (Open Table in a new window)

Type of Cancer |

General Population Risk (by age 70 y) |

Lynch Syndrome Risk (by age 70 y) |

Endometrial |

1.5% |

30-40% |

Ovarian |

1% |

9-12% |

Upper Urinary Tract* |

Less than 1% |

4-10% |

Stomach |

Less than 1% |

13% (higher in Asians) |

Small Bowel |

Less than 1% |

1-3% |

Brain |

Less than 1% |

1-4% |

Biliary Tract |

Less than 1% |

1-5% |

* Those with HNPCC with MSH2 mutations are at an increased risk not only for upper urinary tract tumors but also for bladder cancer.

Turcot syndrome

Formerly considered a separate disorder from familial adenomatosis polyposis (FAP), Turcot syndrome is clinically characterized by both multiple colorectal adenomas and primary brain tumor. In 1995, Hamilton et al demonstrated that this association may result from at least two distinct types of germline defects: a mutation in the APC gene (which represents two thirds of cases and is responsible for FAP) and a mutation in mismatch repair (MMR) gene PMS2 or MLH1 (which represents one third of cases). [11] Medulloblastoma is most common with APC mutations, whereas glioblastoma is most common with MMR gene mutations.

Muir-Torre syndrome

This is a type or variant of HNPCC and is characterized by a mutation in MSH2 and/or MLH1 genes, although some cases have been described with mutations in the MSH6 gene. Muir-Torre syndrome accounts for much less than 1% of all hereditary colorectal cancer cases and is characterized by the typical features of HNPCC and increased risk of developing sebaceous gland tumors, such as sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas. [12]

Patient Education

Intestinal Multiple Polyposis and Colorectal Cancer (IMPACC)

IMPACC is a national support network founded in 1986 to help patients and families dealing with familial polyposis and hereditary colon cancer. It provides information and referrals, encourages research, and educates professionals and public. Phone support network, correspondence, and literature are available.

Intestinal Multiple Polyposis and Colorectal Cancer PO Box 11 Conyngham, PA 18219

Phone: 570-788-3712 Fax: 717-788-1818

E-mail: impacc@epix.net

American Cancer Society (ACS)

The ACS provides assistance to those with cancer. Check the telephone directory for your local chapter.

American Cancer Society National Home Office 250 Williams St NW Atlanta, GA 30303

Phone: 1-800-227-2345

Website: https://www.cancer.org/

In addition to offering information, the ACS has a number of educational programs and informational materials. Call the ACS for information regarding their local chapters.

Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer (CGA-IGC)

The CGA-IGC was established in 1995 "to improve understanding of the basic science of inherited gastrointestinal cancer and the clinical management of affected families." The CGA-IGC's focus is to provide education to professionals and patients, access to clinical and chemoprevention trials, resources for developing new genetic registers, and a forum for collaborative research.

Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer Dr. James Church Director, David G Jagelman Colorectal Cancer Registries Cleveland Clinic Foundation Department of Colorectal Surgery 9500 Euclid Avenue, Desk A30 Cleveland OH 44195

Phone: 216-444-3540

Website: https://www.cgaigc.com/

Johns Hopkins Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry (JHHCCR)

The JHHCCR provides education and information about hereditary colorectal cancer.

Johns Hopkins Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry Phone: 410-955-3875; 1-888-77-COLON (1-888-772-6566)

E-mail: hccregistry@jhmi.edu

Website: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/colorectal.html

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

The NCI is the US government's principal agency for cancer research. A live help line in English (https://livehelp.cancer.gov) or Spanish (https://livehelp-es.cancer.gov) is open Monday through Friday, 8:00 am to 11:00 pm Eastern Standard Time, and offers free information on all aspects of cancer. Information on clinical trials is available at https://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/ .

National Cancer Institute Information Service (CIS) BG 9609 MSC 9760 9609 Medical Center Drive Bethesda, MD 20892-9760

Phone: 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237) (Monday to Friday, 8 am to 8 pm Eastern Standard Time)

Website: https://www.cancer.gov/

-

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Example of an autosomal dominant pedigree.

-

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Diagnostic approach for patients with colorectal tumors.