Trish and John Deford hope to assist students who are battling addictions like the one that claimed their son, CU Boulder alumnus Sam Deford, through a new scholarship fund

John, Trish and Sam Deford enjoyed a trip to Iceland in 2015. It was the last time they saw him. At the top of the page, Trish and Sam Deford share a moment. Images courtesy of Trish and John Deford.

Things were looking up for Sam Deford. He had a good job at a hip, digital-marketing firm. He’d rekindled his relationship with his girlfriend, and he was eager to see the movie version of “The Martian,” which, he’d hoped to be able to report, wasn’t as good as the book.

On Oct. 1, 2015, he enjoyed an evening with friends, watching movies and playing guitar. By the next morning, he was gone. The cause of his death: an overdose of fentanyl, an opiate that is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin. He was 27.

This was not how or when his life should have ended.

His parents, Trish and John Deford, share his story in the hope that other college students escape his fate, and that others may successfully break an opioid addiction and find support for their recovery.

They want to raise awareness and funds for the students at the University of Colorado Boulder Collegiate Recovery Center, which didn’t exist when Sam Deford was a student here but is now a program that helps students like him to establish and maintain recovery from substance use.

Beginning on May 10, Trish Deford will begin a walk of 500 miles on the Camino de Santiago, a famous Christian pilgrimage route across northern Spain. As she put it:

Trish Deford on a training walk in Florida this year.

“I will walk over mountain and field, through village and town, in memory of my son, Sam, in tribute to our favorite way to spend time together and as a way to raise funds for a scholarship in his name.”

Sam Deford was born and reared in Maryland and graduated from CU Boulder in 2012 with a degree in physics and a minor in mathematics. During his junior year, Sam had shoulder surgery. For pain, the doctor gave him “a big jar of OxyContin,” Trish Deford said, adding that Sam’s opiate addiction began then.

But his parents didn’t know that he was struggling with substance use until after he graduated from CU Boulder.

“Sam managed, we do not understand how, to finish his degree,” Trish Deford said. After graduation, Sam stayed in Colorado, got a job at a pizza place and became less communicative with his parents.

Concerned, John Deford called Sam’s boss in Boulder to ask what was going on. The boss said there were issues. John Deford pressed for answers: What issues? Drugs, pot? Heroin, the boss said.

Trish and John Deford organized an intervention. They summoned a psychiatrist who prescribed methadone, which is used to help people stop using heroin. They also hired Sam a life coach.

Before the crisis point, Trish and John Deford had no inkling that he was suffering from a substance-use disorder.

Sam Deford in Moab, Utah, which his mother describes as "his favorite place.

“Once he got into rehab and told us his history, we were shocked at the drug use he’d been engaged in since the age of 14,” said John Deford, who believes Sam chose CU Boulder for its well-regarded physics department, though also went looking for the parties that often surround college campuses.

About six months after the intervention, Sam himself asked for more help. “He realized he was sliding and called home and said, ‘I need to go into rehab,’” Trish Deford recalled.

Sam went into a couple of treatment centers on the East Coast and ultimately came out “looking good and feeling great,” Trish Deford said. He achieved nearly three years of sobriety, during which he became director of creative strategy at Fractl, a data-driven content marketing agency in Florida.

“Sam was a funny guy with a gentle side,” Trish Deford said, adding that he was creative and smart. “He had unbelievable problem-solving skills, but the one problem he couldn’t solve, his addiction, ultimately led to his death.”

She described her journey on the Camino de Santiago as an attempt to find some peace for herself and help for others. “I hope this trek will allow me discover inner strength, peace and find healing while raising awareness of the tragedy of addiction,” she said.

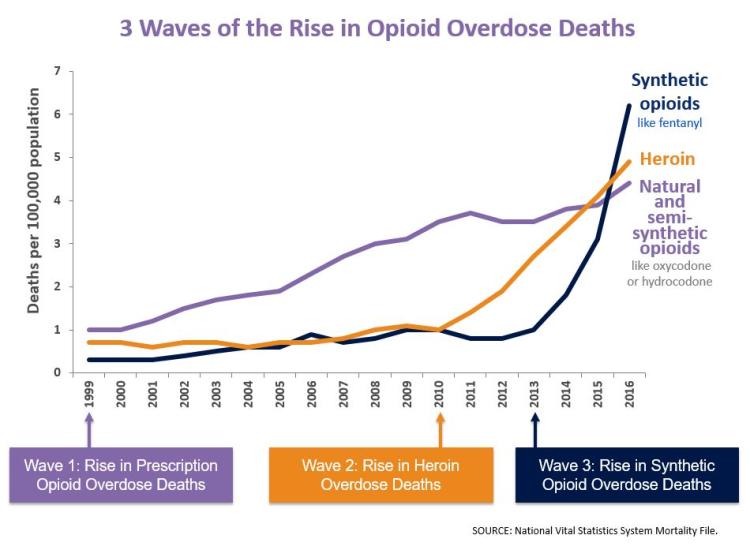

This chart from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows three distinct waves in the opiod crisis. Learn more about the CDC analysis on its website. Image courtesy of CDC.

By soliciting pledges and other support, she hopes to raise $100,000 for the Sam Deford Memorial Fund, which supports students involved with the Collegiate Recovery Center at CU Boulder.

Supporting this fund helps advance the nationwide movement to address substance use on college campuses, while supporting individual students in recovery who need help to complete their educations, Trish Deford said.

Deaths from drug overdoses have risen sharply in the last two decades. Between 1999 and 2016, more than 350,000 people in the United States died from opioid overdoses, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC reports that the opioid crisis has come in three distinct waves: The first wave was fueled by rising rates of opioid prescriptions in the 1990s. The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in heroin overdoses. The third wave began in 2013, and the CDC says it has been marked by an exponential rise in deaths involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

In 2016, 115 Americans died each day from opioid-related overdoses. That is a five-fold increase from 1999, and universities are not immune from the devastation, experts observe.

• 463 students attended social events hosted by center

• 412 individual recovery coaching sessions were provided to students by the center

• 736 students attended outreach events and trainings led by the center

• 3,154 total student interactions with peer support services were provided by the center

Leading researchers also note that it is important to know that people do recover from addiction and go on to lead full and productive lives when they receive treatment and support.

Such statistics underscore the rationale for CU Boulder’s Collegiate Recovery Center, and it helps explain the Defords’ work to support the center and the students it serves.

They were thrilled to discover that CU Boulder now has a program on campus that can help current students with their recovery so they can be successful and establish a good foundation for maintaining their recovery after they graduate.

Recent studies show that 96.6 percent of students who participate in a collegiate recovery program go on to maintain their recovery following graduation.

As Trish Deford observed: “These students have worked hard to overcome addiction and deserve all the support we can give them.”

Trish and John Deford began trekking the Camino de Santiago on May 10. John will walk with her for 10 days, and she plans to finish the trek by herself. Follow her journey on her blog site.

The program provides a home for a healthy, recovery-oriented community in the heart of campus along with free support meetings, sober social events, one-on-one recovery coaching by professional staff and peer mentors.

The CUCRC also has campus housing where students can live together in a fully substance-free community that supports their recovery.

Students in recovery that are involved with the CUCRC serve as peer mentors for other students and lead outreach trainings for RAs in the residence halls, student organizations, athletic teams, Greek life and at local high schools.

Collegiate recovery programs are described as one of the most innovative and effective solutions for helping students struggling with substance use and creating a campus culture that embraces health, wellbeing and recovery, according to the Association of Recovery in Higher Education.

Students who participate in the CUCRC maintain their recovery and also excel academically. Since the opening of the center, 95 percent of CUCRC students have successfully graduated (compared to the current 69 percent six-year undergraduate graduation rate for the campus).

Students in recovery also tend to have a higher GPA on average than the general university population and are often highly successful in other endeavors thanks to the emotional health and wellness that they are able to establish as part of their recovery, the center’s leaders say.

There are more than 100 collegiate recovery programs across the country, with more getting started every year. The CU Boulder program, founded in 2013, is the first to be established in Colorado and has been offering guidance and support to students and administrators at other universities in the state who are working to build recovery support on their campus, including Colorado State University and the University of Denver.

To learn more about collegiate recovery and view a list of current programs, visit the Association of Recovery in Higher Education website at collegiaterecovery.org.