Sensible people are vigilant about online security as a matter of course, ever alert to the possibility that someone might breach their passwords for the purposes of stealing. Like the ones who drink the recommended number of units and make sure their dogs never have chocolate, I don’t know people like this, but I’ve heard they exist.

This article includes content hosted on s3.amazonaws.com. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as the provider may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

As bad as theft is, there is a greater peril, which is what prompted video game developer Zoe Quinn to devise Coach, a series of walk-throughs to protect yourself online, and feminist activist Anita Sarkeesian to create her online safety guide.

If you are monumentally unlucky, you can find yourself in the eye of the internet’s fury, and the range of things cyber-competent strangers can do to you is wide and extremely nasty. Doxing is when someone hacks into your account and broadcasts your personal details – from there, the death and rape threats that are routine for women with a significant online presence take on a hideous new plausibility. You are vulnerable to acts of baroque vandalism, like swatting – where an emergency call is faked from your address and the police storm your house – and, of course, still theft.

While these storms are depressingly often triggered by a feminist moment, Quinn’s case mainly stemmed from the fact of her being female, and the attacks on her were life-alteringly intense, and globally arresting. Most of the other cases I can pluck from memory involve an act of mild feminism: a lawyer objecting to casual sexual objectification; a scientist rebutting the idea that women only go to the lab to fall in love. But the only way you could be sure that you would never find yourself a target would be to avoid not just feminism but any act of strident self-assertion. From that perspective, it is actually easier to protect your passwords.

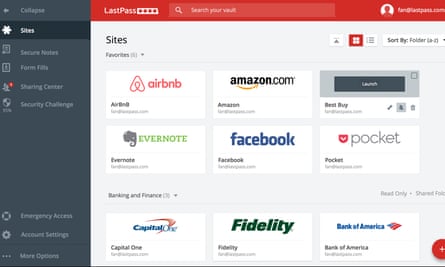

Start by downloading a password management tool – I used LastPass. You go through your accounts in this order: Google, Yahoo, Microsoft, Apple, Dropbox, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, PayPal, eBay, Amazon, and then any not-so-universal sites (Ocado and Outnet, basically). LastPass generates new passwords for them, which will then autofill through a snowflake button on the browser. The process of changing is painful; it shames me to admit that, more than once, I incorrectly saved the new password on to LastPass, then had to go through hell to change it again, ending up with multiple versions of the same site in my “vault”. I am still locked out of Facebook but this is for the best, I think. It should take about an hour – it took me about two.

Then you register for two-step verification where you can, meaning whenever you want to make a transaction, you are texted a code on your mobile. This sounds like more hassle than it is, since it’s rare for your mobile to be very far away. Even if you are an inveterate non-worrier, you will feel more secure after this. Especially if you are someone whose passwords were all variations on the same formation, and you previously spent your life trying to remember the minute differences, you’ll be amazed at how much free time you now have and can get on with learning an instrument or a new language.

Personal data in the public domain is more complicated: if you have a domain name, your details may be accessible through Whoisnet and you will have to contact the service you bought the domain through and establish new privacy settings. Otherwise, the best way to see what’s publicly available is to type your address, in inverted commas, into Google: immediately, you will probably find yourself on Freeelectoralrolls.com, but those of a paranoid bent will have already asked via their local electoral registration office to be kept off the open records.

Other than that, the main porosity I found was Companies House. If you are a company director – and this isn’t as niche as it sounds, since it includes organisations with charitable aims but not charitable status – your home address will be listed, unless you have alerted them to some specific threat. In the US, there are also a number of websites that list people’s addresses – such as Spokeo – and you will have to contact each of them directly to ask to be removed. Apart from Freeelectoralrolls.com, this is not such big business in the UK.

Other possible breaches are: failure to choose the right privacy settings on your website or chosen social media, and that is relatively simple; or leaks via your family members, especially on a site like Facebook, where you could have the most stringent settings but find that your location could be correctly identified most of the time via your idiot children. You may, if you haven’t lost the will to live, want to go through all these processes with the other members of your household.

Hardware compromises are where things become complicated: signs that your computer has been hacked include windows opening on their own, sudden slowness, hard-drive grinding. Mac has a programme called Little Snitch which will tell you when data is being sent from your computer, and Wireshark is a network protocol analyser. Yes, exactly: your paranoia has to be at quite high levels for this level of attention to be worthwhile.

The journalist Geoff White and techie Glenn Wilkinson have done some bracing work, meanwhile, on how much data can be gathered about you and your whereabouts via your phone or mobile device. The tech journalist Christian Payne summed this up neatly: the only way to protect yourself from the possibility that someone could steal your identity or discover your whereabouts via your phone is to carry it in a lead-lined wallet and not use it.

Incidentally, the same is true of your passport – its details can be read from a distance, and therefore it leaks information constantly. Generally, avoid public Wi-Fi networks, keep your system updated, and download Prey on to every device, so you can wipe it remotely if it is stolen. But there is only one way to avoid all the security breaches presented by a mobile phone, and that is by not having a mobile phone.

Despite Quinn’s work simplifying the process, it remains quite an undertaking, and I resented it. Sometimes men launch these attacks on each other, hack each other in displays of techie braggadocio, but it is essentially yet another unwanted cost of being female.

Virtual violence raises the familiar arid rage in me that all violence against women does; the frustration that it never ends, only grows new limbs. So I get no satisfaction from my new unhackability, but I do recognise that it was worth doing.

If you are targeted online, there are useful guides here and here. They include lists of support services, mainly in the US. If you are in the UK, there is a useful directory of available support here.

The Guardian’s head of information security, Dave Boxall, and a systems editor, John Stuttle, will be available from 1pm BST to answer your questions about digital security. Please use the comment thread below to ask your questions – comments that are not questions about security will be considered to be off-topic.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion