On a hot August afternoon in 2000, four Americans arrived for a secret meeting at the central London penthouse flat of an Indian billionaire drug manufacturer named Yusuf Hamied. A sixth person would join them there, a French employee of the World Health Organisation, who was flying in from Geneva, having told his colleagues he was taking leave.

Hamied took his guests into the dining room on the seventh floor. The room featured a view of the private gardens of Gloucester Square, Bayswater, for which only the residents possess a key. The six men sat round a glass dining table overlooked by a painting of galloping horses by a Mumbai artist (Hamied has racehorses stabled in three cities). The discussion, which went on all afternoon and through dinner that evening at the Bombay Palace restaurant nearby, would help change the course of medical history.

The number of people living with HIV/Aids worldwide had topped 34 million, many of them in the developing world. Hamied and his guests were looking for a way to break the monopoly held by pharmaceutical companies on Aids drugs, in order to make the costly life-saving medicines available to those who could not pay.

Hamied was the boss of Cipla, a Mumbai-based company founded by his father to make cheap generic copies of out-of-patent drugs. He had met only one of the men before – Jamie Love, head of the Consumer Project on Technology, a not-for-profit organisation funded by the US political activist, Ralph Nader. Love specialised in challenging intellectual property and patent rules. For five years, he had been leading high-profile campaigners from organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières in a battle to demolish patent protection.

Patents grant protection on inventions, guaranteeing those who hold them a period of monopoly to recoup costs – in the case of drug companies, this can be as much as 20 years. With no competition, pharma companies can charge whatever they want. Love, an economist and self-confessed patent nerd, had taken on politicians, civil servants and corporate lawyers, arguing against unfair monopolies on products from software to stationery. His overwhelming concern at that point was the many millions of lives cut short for want of affordable medicines. He had been asking everybody he could think of, from the United Nations to the US government, one question: how much does it actually cost to make the drugs that keep somebody with HIV alive?

“Watching Jamie with government officials who are sceptical is a thing of intellectual beauty, because there really is nobody who can rebut him when he gets under way,” said Nader in September on his radio show in southern California. “Jamie is a global hero. He has saved many, many thousands of lives by beating Big Pharma and reducing the cost of drugs for poor people overseas.”

Love had flown from his home in Washington to London with Bill Haddad, an investigative journalist who had been nominated for a Pulitzer prize for exposing a pharmaceutical company cartel that was fixing the prices of antibiotics in Latin America. Haddad was now the CEO of a company called Biogenerics, which made cheap copies for the US of expensive branded medicines, once they were out of patent.

The meeting was confidential, because their targets were the wealthy and powerful multinational pharmaceutical companies who were fierce in defence of their patents. For four years, a three-drug cocktail costing between $10,000 and $15,000 per year had been available to treat people with HIV in the US, and other affluent countries. But in Africa, a diagnosis remained a death sentence. In 2000, more than 24.5 million people in sub-Saharan Africa had HIV. Many of them were young, many also had children and could not afford life-saving treatment. Love had a word for this state of affairs: racism.

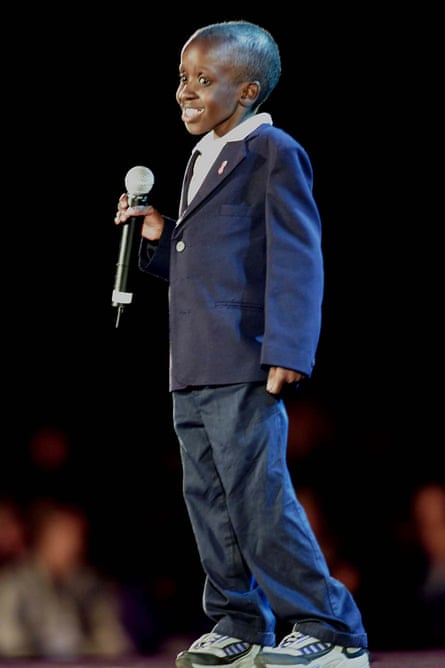

The month before the Gloucester Square meeting, 12,000 people from all over the world had convened in Durban, South Africa for a fiery and impassioned International Aids Conference, to demand affordable drugs. There were marches in the streets, and singing, dancing and the throb of drums in the conference hall. A white constitutional court judge, Edwin Cameron, took the platform to declare that he was HIV‑positive and to denounce a world in which he could buy his life but others had to die. A small boy born with HIV, named Nkosi Johnson, moved people to tears with a plea for acceptance and understanding. He died, without treatment, the following year, aged 12. Nelson Mandela, the former president, closed the conference with a statesmanlike appeal for action.

At the London meeting, Love had a question for Yusuf Hamied. How much, he asked, as they sat around the glass table in their shirtsleeves in the summer heat, does it cost to make Aids drugs?

Hamied had been making the antiretrovirals that hold HIV at bay for a while. In India, thanks to the 1970 Patents Act, in which his father had been instrumental, drug patents granted in the US or Europe did not apply – yet. (The World Trade Organisation’s trade-related intellectual property rights, or Trips, agreement requiring all nations to recognise international patents did not come into effect in India until 2005.) The cost of manufacturing a drug, Hamied told Love, is barely more than the cost of the raw materials.

By the time the visitors headed back to their hotel, a plan had been hatched. Hamied would make Triomune, a cheap, once-daily pill combining the three Aids drugs sold by different manufacturers for such huge sums in the US and Europe, and sell it in Africa and Asia for a fraction of the cost.

Fifteen years on, it is no longer just the poor who cannot afford the drugs they need. New medicines for lethal diseases such as hepatitis C and cancer have been launched on the global market at such high prices that the richest countries in the world are having to find ways to ration them. And Jamie Love is back in the fray.

In 2010, the cause Jamie Love has fought for all his life suddenly became intensely personal. His wife and colleague, Manon Ress, was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer. Ress asked her doctor how long she had. Not 10 to 20 years, she was told, but probably five to 10. That was good news. Long enough to get a dog.

Within days of her diagnosis, Ress started chemotherapy, but since both her mother and her sister had suffered from cancer, it was possible she had an inherited genetic propensity to the disease that could affect which treatment she should be given. There were delays in getting the test – probably, Love believes, because it was patented.

“It took weeks before we got the result back and I was so angry,” said Love. “You are just reeling with not knowing what the hell is going on and not even knowing what the stages mean and trying to figure everything out. And then you realise that the reason why she didn’t get the test is because the fucking price was so high that she wasn’t recommended for it earlier. It is very cheap to perform but very expensive because of the patent. This is sort of crazy.”

Ress’s aggressive cancer responded to the drug Herceptin for a time. When that stopped working, Ress was prescribed T-DM1, marketed by the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche as Kadcyla. The drug was originally listed in the UK at £90,000 per patient per year, making it the most expensive breast cancer drug ever sold.

“I have it every three weeks and there are very few side-effects – dry eyes and a dry mouth and joint pains,” Ress told me. That was trivial stuff compared to the chemotherapy, which had given her infections, stopped her tear ducts working and wrecked her sight, which had to be corrected by a cataract operation. And Kadcyla worked straight away. “Immediately three tumours disappeared. There is still one on the lung, but that is getting smaller.”

Love struggled to understand how the tragedies he had fought against all his life had turned up at his own front door. Thanks to him and his colleagues, Aids drugs are now affordable everywhere in the world, but advanced cancer drugs are not. And while Ress could – through her insurers – buy extra years of life, she and Love were outraged that other women, even in rich countries, did not have the same opportunity.

Initially, Ress did not want to speak publicly about her illness and treatment. But she knew that the willingness of people to be open about their HIV-positive status was one of the reasons why the global battle for Aids treatment was won. Ress decided she could advocate, with a passion. “It is outrageous to me that some women are not getting the drug, depending on where they were born,” she said. “It should not be a matter of luck.”

Ress’s fight for survival shifted Love’s perspective, he explained to me over a pint of lager on a chill evening in London last spring. He had spent years focusing on drugs that were just coming to the end of their patent life – drugs that were by that time almost two decades old. But better cancer drugs are being developed every year. For the sake of women like his wife, Love realised he needed to be working on access to new drugs, not just the ones coming to the end of their patent protection.

At 66, Love still has the broad shoulders of a man who has known hard physical work. On the night we met, he was preparing to present his radical plan to slash the cost of Kadcyla. He was also looking forward to a video call with Ress, to tell her about the conference in Cambridge on intellectual property rights where he had spent the previous two days. Ress was in Washington DC, where she walks her beloved Airedale terrier for around six miles every day.

Since Kadcyla first came on the market, after protracted negotiations, Roche has agreed to reduce the price. (Details of these negotiations are kept secret from the public and the company’s competitors.) However, the NHS still views it as too expensive for general use.

In response, Love came up with a scheme. In October, a coalition of campaigners set up by Love sent a letter to health secretary Jeremy Hunt, proposing a solution as radical and surprising as his scheme for Aids drugs. The UK government, Love urged, should override the patent on Kadcyla, pay Roche compensation – a process known as compulsory licensing – and authorise a company to make cheap generic copies.

It was a bold, unprecedented move, challenging a first-world government to take on Big Pharma. Yet there was an undeniable logic to it. The government could not afford to treat all the women who needed the drug at the price Roche wanted. And if Love could persuade the government to embrace his scheme by issuing a compulsory licence for T-DM1, it would set an important precedent – one that could change the cosy relationship between rich countries and Big Pharma for ever.

Jamie Love has never worked in healthcare. His crusade for access to medicines developed out of an early recognition that the drive for profit of big corporations was harming the poor. After graduating from high school, Love left his home town of Bellevue, across the lake from Seattle, and went to Alaska to work in the fisheries. When he took his first job in a cannery, he was lodged with a Filipino crew. About a month later he was moved into the white workers’ bunk house. “I had much better accommodation, a raise, more privileges and things like that and they put me in a different union. But I’d got to know the Filipinos and I was struck by the injustice of the whole thing,” he said.

Two years later, he was looking for work in Anchorage, and while collecting unemployment benefit, he started to become aware of the damaged lives around him. “They were runaways, drug addicts. They were outside the system. So I was eventually involved in this social services operation. We set up a free medical clinic and eventually a free dental clinic, a legal clinic and other things as well.”

People would arrive at the clinic with possible cancer symptoms, saying they were unable to find a doctor who would see them because they were uninsured and relied on Medicaid, the state-funded healthcare for the poor. Love and his friends rang all the local doctors they could find and asked whether they would accept Medicaid patients – and then got the local papers to run a list, naming and shaming those who refused. The press ran the story with headlines such as: “Doctors to patients: drop dead”.

Love discovered he was not cut out for social work. On a personal level, he struggled to cope with the individual tragedies around him. So he set out to tackle poverty and social injustice by changing the underlying system. In the late summer of 1974, he set up the Alaska Public Interest Group, and campaigned for oil companies to hand over a portion of their revenues to the local community.

As his campaigning work grew, Love, who only had a high school education, felt that he needed more formal training and some academic credentials. Supported by recommendations from the governor of Alaska, among others, he leapfrogged undergraduate college and was admitted to a graduate programme on public administration at the John F Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. He then joined the doctoral programme at Princeton.

Love had met his first wife, an artist, in Alaska, and they had a son. When they separated, Love found himself living alone in Princeton with a four-year-old. One of his neighbours in accommodation for students with families was a young Frenchwoman, separated from her husband, who also had a four-year-old boy. She was the daughter of a French artist and an American journalist. Her name was Manon – like the opera, said Love.

“Our kids were playing together, so she was my babysitter and I was her babysitter,” recalled Love. “If she went out and dated someone, I’d take care of her kid. She’d lend me her car if I was taking someone out. So eventually I took her to a circus and then I was quite smitten by her.”

In 1990, Love began working at the Center for Study of Responsive Law, a non-profit consumer rights organisation founded by Ralph Nader. Love focused on intellectual property rights. In 1995, he started the Consumer Project on Technology, now called Knowledge Ecology International. He worked on the investigation of Microsoft’s monopoly position in the web browser market. “I was the only one in the office who was really very techie, so I took the lead in beating up on Microsoft for about a year,” said Love. “Which is why I’ve got this deep, bad relationship with Bill Gates.” Years later, they clashed over access to medicines: Gates, who has put millions into vaccine research, strongly supports patents as an incentive to drug companies to invent new and better medicines.

Love had been working on the question of what constitutes a fair cost for medicines, on and off, since 1991. But the moment that would shape Love’s career came in the spring of 1994, when he got an invitation from Fabiana Jorge, a lobbyist for the Argentinian generic drug industry. Argentina, like India and Thailand, had a robust generic drug industry making cheap versions of medicines invented in north America or Europe. But the Argentinian government was coming under intense pressure to enforce international drug patents. The US government, which enjoyed very good relations with Big Pharma, wanted the Argentinians to implement the Trips intellectual property rights treaty and prevent generic copies of medicines being made.

Jorge was rounding up anybody she could find who had ever been critical of Big Pharma, including an adviser to Bill Clinton in the White House, to speak at a conference in May, held by the Latin American pharmaceutical industry in San Carlos de Bariloche, in the snow-covered Andes. Love accepted the invitation, and when he and his team arrived in Buenos Aires, they went straight to the US Embassy and demanded an explanation of what the US was up to. He was told that the Clinton administration was putting pressure on Carlos Menem, the Argentinian president, to issue an executive order upholding drug patents. As he listened to the embassy official’s explanation, Love became increasingly angry. He recalled his outburst: “And you are willing to have the president of Argentina become a dictator, bypass all the legislative safeguards of a democratic system? That’s what we’re doing in the United States? So these people that are really poor will pay higher prices for drugs. That’s America, right? It’s like – you’ve got to be kidding! I had no idea! It was like – wow!”

He would spend the next 20 years battling for access to drugs for the poor.

Big Pharma has a simple justification for charging high prices for drugs: it costs a lot of money to invent a medicine and bring it to the market, so the prices have to be high or the companies will be unable to afford to continue their important research and development (R&D). The figures drug companies usually cite are from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development in Boston, Massachusetts, which describes itself as an independent academic institution, despite the fact that it receives 40% of its funding from industry. In 2000, it put the cost of bringing a drug to market at $1bn. By 2014, that had risen to $2.6bn.

But those figures have been contested by Love and other campaigners. Many drugs begin as a gleam in the eye of a university researcher: somebody in academia has a bright idea and pursues it in the lab. Much medical research is funded by grants from public bodies, such as the US National Institutes of Health, or, in the UK, the Medical Research Council. When the basic research looks promising, the compound is sold, often to a small biotech firm.

Big Pharma has its own teams of lab researchers, but over the years the biggest drug companies have increasingly gained new drugs by buying smaller biotech firms with promising compounds on their books. Campaigners argue that the actual R&D carried out by the big profit-making companies – and the cost – is much less than they claim. A Senate finance committee carried out an 18-month investigation into the cost of the new Gilead hepatitis C drug, Sovaldi. In December 2015, it found that the price, set at $1,000 a pill, did not reflect the actual cost of R&D. Gilead stood to recoup far more than the $11bn it had paid to acquire the small biotech company, Pharmasett, that had produced Sovaldi and a follow-on treatment, Harvoni. “It was always Gilead’s plan to maximise revenue and affordability, and accessibility was an afterthought,” said Senator Ron Wyden at a news conference to announce the findings.

Even where a company has invented and developed the drug itself, there are other factors that push up the price. The cost of developing the many drugs that have been through trials and failed to work are factored in – more controversially, so is advertising and marketing.

Love was figuring out how to challenge these cost factors back in 1994, when Ellen t’Hoen of Health Action International in the Netherlands was organising a meeting to figure out what the consequences of the Trips agreement would be. Love emailed her to ask if he could attend, and she booked him to speak. They have been close collaborators on access campaigns ever since.

“He blew everyone out of the water,” t’Hoen said. “It was one of those visionary Jamie presentations, linking patents to questions of [alternative] financing for R&D. He is always way ahead of the game. He is always thinking about things that most people don’t even understand.”

Over the next few years, Love became known for his formidable grasp of intellectual property rules. His papers and blogs posted on the internet were picked up around the world. In 1998, Bernard Pécoul from Médecins Sans Frontières got in touch. Love didn’t know what MSF was, but Ress did. They were cool, she said: he absolutely had to speak to them.

A powerful alliance was beginning to form against Big Pharma. There were millions of people with HIV/Aids in South Africa by the end of 1998 – more people were dying of Aids there than in any other country. Yet at that critical moment, some 40 drug companies including the UK’s GlaxoSmithKline brought a joint legal action in Pretoria to block the South African government from buying cheaper medicines from abroad. Over three years, they retained almost every patent lawyer in South Africa and spent millions preparing a case that would deny treatment to the poor in the interests of profit.

Finally, in response to an international outcry, the drug companies abandoned the case, but not before the action had done lasting damage to their public image. Aids activists in the US and in Europe accused the companies of having blood on their hands. In this turbulent atmosphere, it was clear to Love that if campaigners wanted affordable medicines of all sorts for the poor, they should be focusing their energies on Aids drugs – public opinion was on their side and millions of lives were at stake. “I’d been following Aids but only really on the periphery of it and not very involved,” Love recalled. “I felt like, oh my God, I’m actually going to be able to do something about this.”

Trials had shown that a three-drug cocktail of very expensive antiretroviral drugs could not only keep people with HIV alive but healthy enough to live and work normally. The cost, around $15,000 a year per patient, was out of the question in sub-Saharan Africa.

The way to drive the price down, Love believed, was through compulsory licensing. The patent owner would get compensation, but not the enormous profits they might have expected.

At first, his idea met with strong resistance. “Compulsory licensing was considered a mechanism that we would never use,” said t’Hoen. It might be illegal and it would certainly outrage Big Pharma, whose lawyers would fight it. Love did not care. He was more than willing to take Big Pharma on.

In March 1999, Love’s Consumer Project on Technology cohosted a meeting of around 60 public health and consumer NGOs in the Palais des Nations in Geneva, on compulsory licensing as a means to get drugs to people who needed them, and could not afford them. There was passion and excitement at what the drugs company Merck later derided as a “boot camp” for smashing patents. There were representatives from the US patent trademark office and drug companies, people from the European Commission and WTO, and Aids activists – anyone who would be affected by the issue wanted to hear how this might work.

With their demands honed and targeted, the campaigners won a resolution from the World Health Assembly, the policy-making annual conference where all governments are represented. The WHA effectively supported not only access to medicines but, specifically, compulsory licensing. Love had made the resolution as sharp and pragmatic as possible, he said. “Otherwise it’s just another crappy WHA resolution that comes and goes and nobody pays any attention.”

He and t’Hoen were sometimes frustrated by the levels of incomprehension that met their work on trade agreements and drug pricing. “One time he looked at me and said, ‘Ellen, let’s face it – we’re nerds on this issue.’ But that’s part of his strength. He does not let go. His organisation is relatively small. If you compare it to an organisation like MSF, it is nothing. It is a couple of people. Yet the things they managed to do.”

When Yusuf Hamied met Love and the rest of the group in August 2000, Hamied said he was already manufacturing the individual drugs needed to treat people with HIV. He was prepared to make the drugs available at low cost, but he needed a guaranteed market. He had made a cheap version of AZT, the first Aids drug, in 1991, but had been forced to throw away 200,000 bags of the chemical because the Indian government did not have the money to buy it, even at $2 a day. He agreed to make a single drug to treat HIV at low cost, if his guests would help him market it.

The following month, at a meeting of the European Commission, Hamied publicly offered to make this three-drug Aids cocktail for $800 a year. His company, Cipla, would also help other countries make their own Aids drugs, he announced, and give away the single drug, nevirapine, that prevented mothers from passing HIV to their babies in childbirth. Haddad described it as a moment when you could hear the breath being sucked out of the room.

Hamied waited for his phone to start ringing – but the calls he expected from HIV-hit governments or donor organisations asking to buy Triomune did not come. “And one bright day, on 6 February 2001,” said Hamied, “when I was absolutely despondent that nothing was happening, Jamie rings me up from America and says, I’ve been thinking as to what we should do. Is it possible for you to reduce the price of the drugs to below $1 a day? That was Jamie’s idea.”

Hamied agreed to offer the cocktail to MSF for Africa at $1 a day. With this precedent, Aids drugs would now be affordable for developing countries or donors willing to help them.

Love had won, but he had made enemies in the companies fighting to defend their intellectual property rights. He discovered that private detectives had been hired to spy on him. “One day a guy came over and knocked on our door. We opened the door and the guy said, ‘You don’t know me. I know you. For the past two years it’s been my job to follow what you do every day,’” Love recalled. The man had just been fired from PhRMA (the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America) and wanted to let Love know he was being watched.

Love’s organisation was also struggling for funds. As they moved into global issues, Nader, whose organisation focused on the US, stopped bankrolling them. Other philanthropic foundations in the US pulled out of work on intellectual property (Love believes this was a result of lobbying from drug companies and other corporations that campaigners had targeted). They slimmed down, pared back the staff, stayed in budget hotels, but they kept going.

Manon Ress eventually gave up her teaching job to join Love in Washington DC. They had two children together, a boy and a girl, as well as the two they already had from previous relationships. Love was away a lot, travelling around the world to speak and lobby governments. It put pressure on their marriage. After a bumpy patch, Ress started working with Love at Knowledge Ecology International, campaigning on copyright issues. (It was Ress who decided in 2008 that they should help the World Blind Union, which had been fighting the copyright restrictions on books that prevented them being cheaply adapted to braille and audio versions. She and Love drafted a treaty that would allow exemptions to the normal copyright on books for the benefit of blind, visually impaired, and reading-disabled people. It took five years of hard work to get it adopted.)

After Ress’s cancer diagnosis, the cost of medicines became very personal for both of them. Love started to ask generic firms whether they could make a version of Kadcyla, or T-DM1. He went to see an Argentinian company that also manufactures in Spain. Biological drugs such as T-DM1 are made from living organisms such as sugars or proteins and are complicated to manufacture. To make a biosimilar – a copy of a biological drug – some research and testing is required.

The Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche launched Kadcyla onto the UK market in February 2014 at a list price of £90,000 – the average cost of treatment for a single patient over 14 months. Trials had shown the drug extends life for women with incurable breast cancer by at least six months, but in April 2014, the government’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which decides whether drugs are sufficiently cost-effective to be used in the NHS, turned it down. The Cancer Drugs Fund, set up by the government in 2010 to provide funding when life-extending drugs were judged unaffordable, covered the cost of treatments until April 2015, when NHS England, which runs the fund, declared it would be dropping Kadcyla from the list.

At this point, Love saw an opportunity to make the drug available at a cheap price in an affluent country and set a precedent for access to affordable medicines for the entire world.

Love and Ress approached breast cancer charities in the UK and talked to healthcare experts. On 23 June, they made their way by plane and train and taxi to Oxford to discuss their plan with Dr Mohga Kamal-Yanni of Oxfam, a long-time fellow campaigner on access to medicines in the developing world.

Ress walked rapidly into the small meeting room at Oxfam’s HQ in the Cowley business park. She was small and chic, with a French shrug and a tendency to gesticulate. She wore a pink shirt loose over blue jeans, with pink shoes and handbag. She was quick and funny, often dominating the conversation. The hospitable Kamal-Yanni suggested they might like a bus ride round Oxford after the meeting before a home-cooked meal at her house. “Does he look like a tourist?” laughed Manon, pointing at a sheepishly smiling Love.

For several hours, the pair talked Kamal-Yanni through the proposal. She had many questions, including a major worry: how to get public support in a country where, unlike the US, nobody knows how much medicines cost. Nobody in the UK, she told Love, blames pharma for high prices.

But Love was undeterred. On 1 October, he made his move. The health secretary Jeremy Hunt received a letter from the Coalition for Affordable T-DM1, a group put together by Love and Ress, involving doctors, patients and campaigners in the US, Europe and UK. It proposed that Hunt should tear up the patent on Kadcyla, allowing either the manufacture or the importation of a cheap copycat version. Under the Crown Use provisions of the 1977 Patents Act, the government could legally set aside Roche’s patent and issue a compulsory licence, provided it gave the company “affordable compensation”. Love had found a loophole and invited the British government to use it.

Chris Redd of the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry in Plymouth, one of the signatories, felt the proposal would allow the British public to hold the government to account. “There are 1,500 UK citizens living with breast cancer right now, who could be kept alive by this medication. The solutions are all there in the document. The only question that remains is whether our government is more interested in protecting its citizens or the shareholders of a multinational drug company,” he said.

Love was not so naive as to think the government would open its arms to him. This was a difficult idea for a Conservative government that backs pharma companies and free markets, but it was in a bind, unable to foot the very high cost of new, life-extending drugs that patient groups were clamouring for. Audaciously, Love proposed that the UK government could invest in the research funding, which would give it a financial stake in the drug and ensure it got it at cost price. The UK could even sell it to other countries afterwards and make a profit.

On 4 November, NHS England announced that Kadcyla would stay on the Cancer Drugs Fund list, after Roche agreed, following lengthy negotiations, to lower the price – although it declined to say by how much. Within days, however, Nice announced its final decision on the drug. It was still too costly for general NHS use. Nice is restricted to a threshold of £30,000 for a year of good-quality life per patient or £50,000 for an end of life drug. Kadcyla still broke the ceiling. So while the fund would provide the money to pay for patients in England to get it, those in other parts of the UK could lose out – and the future of the Cancer Drugs Fund is anyway uncertain.

The British government is still pondering Love’s proposal. He keeps going: making frequent trips to Romania, urging its government to embrace compulsory licences on the new hepatitis C drugs, which, with a million infected people, could bankrupt its health system. Ress goes with him to Geneva, or Argentina, when she is needed – and when she can – between her three-weekly visits to hospital. Meanwhile, she walks the dog. “I don’t think my oncologist knows dogs live as long as seven or eight years,” she observed with wry humour. “But I’m going to be here long enough to see another grandchild – and another resolution at the World Health Assembly.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion