Please don’t dirten my shirt with your muddy hands.

Stop cowardising and go and see that girl. Don’t just beep her again, bench her.

Typos? No, we’re speaking Uglish (pronounced you-glish), a Ugandan form of English influenced by Luganda and other local dialects, which has produced hundreds of words with their own unique meanings.

Some will be immediately obvious to English speakers: dirten, meaning to make dirty; cowardising, to behave like a coward.

Others offer small insights into youth culture: beep – meaning to ring someone but to hang up quickly before the person answers. Benching – meaning to drop by on someone you may have a romantic interest in, having evolved from university slang.

Now, Bernard Sabiti, a Ugandan cultural commentator has recorded these colloquialisms in a new book which attempts to unlock what he calls “one of the funniest and strangest English varieties in the world”.

Working as a consultant for international NGOs, Sabiti kept being asked “what kind of English do Ugandans speak?” He felt it was time to “dig deeper and sum-up with something standardised to explain the strange way of speaking.”

The result? A definitive guide to Uglish, from its evolutions to a glossary of hundreds of words.

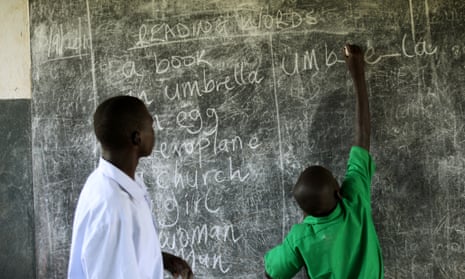

Sabiti says the rise of Uglish directly correlates with a fall in the standards in education. People also read less and spend less time directly interacting with native English speakers, he adds.

Though not exclusive to the younger generation, the majority of words chronicled in his book are influenced by youth culture. What role has the internet played in this? Is social media to blame for a drop in standards?

There is is a specific Uglish Facebook page: “the home of all those who appreciate Ugandans’ efforts at speaking the English language, or those who simply get amused by the absurd attempts”. But for Sibiliti it’s more broadly about popular culture, spread by the internet.

He also credits local musicians for introducing a number of words into the lexicon. For example “wolokoss”, meaning loose talk, or “mazongoto” meaning a big bed, are both lyrics from popular songs.

A piece about Sabiti’s book was posted on the Daily Monitor’s Facebook page, sparking healthy debate amongst Ugandans. Facebook user Fz Wagaba agreed that the problem with was the education system, but also put it down to the “copying of accents and foreign cultures”.

Moses Mwebaze said: “This shouldn’t become a big deal, societies world over create slangs out of English for better understanding”. He added that using slang in real-life conversations shouldn’t be a problem, as long as it didn’t creep into official communications.

Luke Sserugo said he was in “deep giggles” after reading the article and added that English would always be spoken according to the particular vernacular in each society as “that’s how the human brain was engineered.”

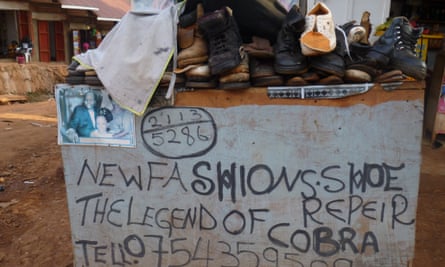

A whole chapter of the book is dedicated to signs showing the misuse of English, in what could be perfect Buzzfeed fodder. Mishaps like these can be amusing but it poses a more serious question: should Ugandans be proud of a language that combines local with global? Or does a perceived slip in standards have broader implications?

Sabiti says that whilst Uglish has created new ways of expressing local concepts, a globalised world means that people should be able to communicate in standard English. “It is important to be understood the same way in Kampala, New York or London,” he says.

But this is not a linguistic phenomena unique to Uganda. “It happens every time a language is introduced into a new local context. Local people have a way of speaking it so it makes sense to them”, says Sabiti

There is “Singlish” a Singaporean English that borrows words from Chinese, Malay and Tamil, and which is very much ingrained in Singaporean identity, despite various government drives to encourage citizens to “speak good English”.

Namlish, spoken in Namibia, which according to The Namibian Sun only has one rule: no grammar. Mumbai, home to 21 million people, has its own version of Hindi called Bambaiya, which incorporates sayings and pronunciations from Marathi, Hindi and English.

Share your slang

Do you live in Uganda? Are you are comfortable Uglish speaker? Do you agree with Sabiti that people need to speak standard English the world over, or are colloquialisms something to be proud of?

If you live in other parts of Africa we’d love to hear from you too. Are you familiar with a hybrid language? Add your favourite sayings in the comments below

Speaking Uglish

- Avail – to make something available

- Beep – to call someone once and hang up before they pick up

- Benching – dropping in on someone you might have a romantic interest in

- Bounce – to arrive somewhere and find someone there or to be turned away from an event

- Buffalo – someone who uses incorrect or inarticulate English words

- Bullet – a leaked exam paper

- Cowardise – to behave timidly or like a coward

- Dirten – to make something dirty

- Live sex – to have unprotected sex

- Mazongoto – a big bed

- Side dish – somebody’s mistress

- Special – an individual taxi (special because a 14 seater taxi is the most common form of transport)

- Vacist – a student on holiday

- Waragi - popular Ugandan crude gin with high concentrations of alcohol. Also used derisively about a drunk person

- Wiseaching – acting like a wiseacre

- Wolokosso – loose talk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion