Richard Platt and his wife, Miranda, began plotting their escape in 2008. They had moved to Austin in the early aughts “for the same reasons that most young people were moving to Austin at the time: to play music and experience life,” Richard says.

They had both dropped out of Howard Payne University, in Brownwood, and those first few years in Austin were like a Jerry Jeff Walker song. “We were really living it up, seeing our favorite bands, swimming in Barton Springs, and attending more house parties than you can count,” he recalls. But things changed when other responsibilities crept in. He and Miranda got married, and kids came soon after. They needed more space, and they found themselves bouncing from apartment to apartment, fleeing skyrocketing rents. They both landed good jobs at Whole Foods, but the expenses kept mounting. “I had moved up into management with the company and was doing well financially, but we never seemed to make ends meet in Austin,” he says. “It seemed at the time that all we were doing with our lives was working and paying bills.”

And so he and Miranda and a group of friends bought a parcel of land near Lockhart, about thirty miles south of the city. They had hoped to create a sort of commune—a rural complex combining sustainable housing and permaculture farming—but it never got off the ground. Juggling that project with living and working in Austin proved too much of a burden. Yet he and Miranda were feeling the pull of Lockhart more keenly than ever. To them, Lockhart was the key to independence, to making their own way in the world.

The town has long cast a curious spell on visitors. Back in 1957 the Architectural Record, a national trade magazine, published an essay penned by architectural historian and critic Colin Rowe, who was teaching in Austin at the time. He saw Lockhart as an exemplar of a Western American town whose square is comparable to “the piazzas of Italy.” But instead of a church at the center, Lockhart is built around its 1894 courthouse, an “exuberant” and “more than unusually brilliant” edifice. He described towns like Lockhart as “very minor triumphs of urbanity.”

The Platts saw it the same way. Why not head into Lockhart full bore, they thought? After all, Richard had always dreamed of opening his own restaurant, and there were only a few on the square. The town’s famous barbecue joints—Smitty’s, Black’s, and Kreuz—catered as much to pilgrims as to locals. Surely the locals would enjoy some variety. And start-up costs were low compared with what they would be in Austin. “It seemed like there was this whole downtown here nobody was using,” Richard says.

In 2012, while continuing to clock in at their day jobs, they began making plans in earnest, scouting locations and brainstorming potential menus. Three years later they dove into the deep end. Partnering with a couple of friends, Chris Hoyt and Layne Tanner, they cashed out their 401(k)s and tapped their savings accounts to open a pizzeria called Loop & Lil’s (named after the parakeets who make a cameo in Townes Van Zandt’s “If I Needed You”). At the time, Lockhart’s square looked much like it had when Rowe visited some sixty years earlier. The 1894 limestone-and-sandstone Caldwell County courthouse, perhaps the finest expression of small-town civic architecture in all of Texas, still majestically lorded over the town. And the other curiously elegant buildings were still occupied by the kinds of businesses you might find anywhere from Waxahachie to Pecos: a barbershop, a bank or two, law offices, insurance agencies.

Loop & Lil’s struck out at first; there was an awkward phase. Some of the pizzeria’s ingredients—artichokes, capers, sun-dried tomatoes—were foreign to a populace accustomed to Domino’s. But the Platts got over that hump. The tables started filling up night after night.

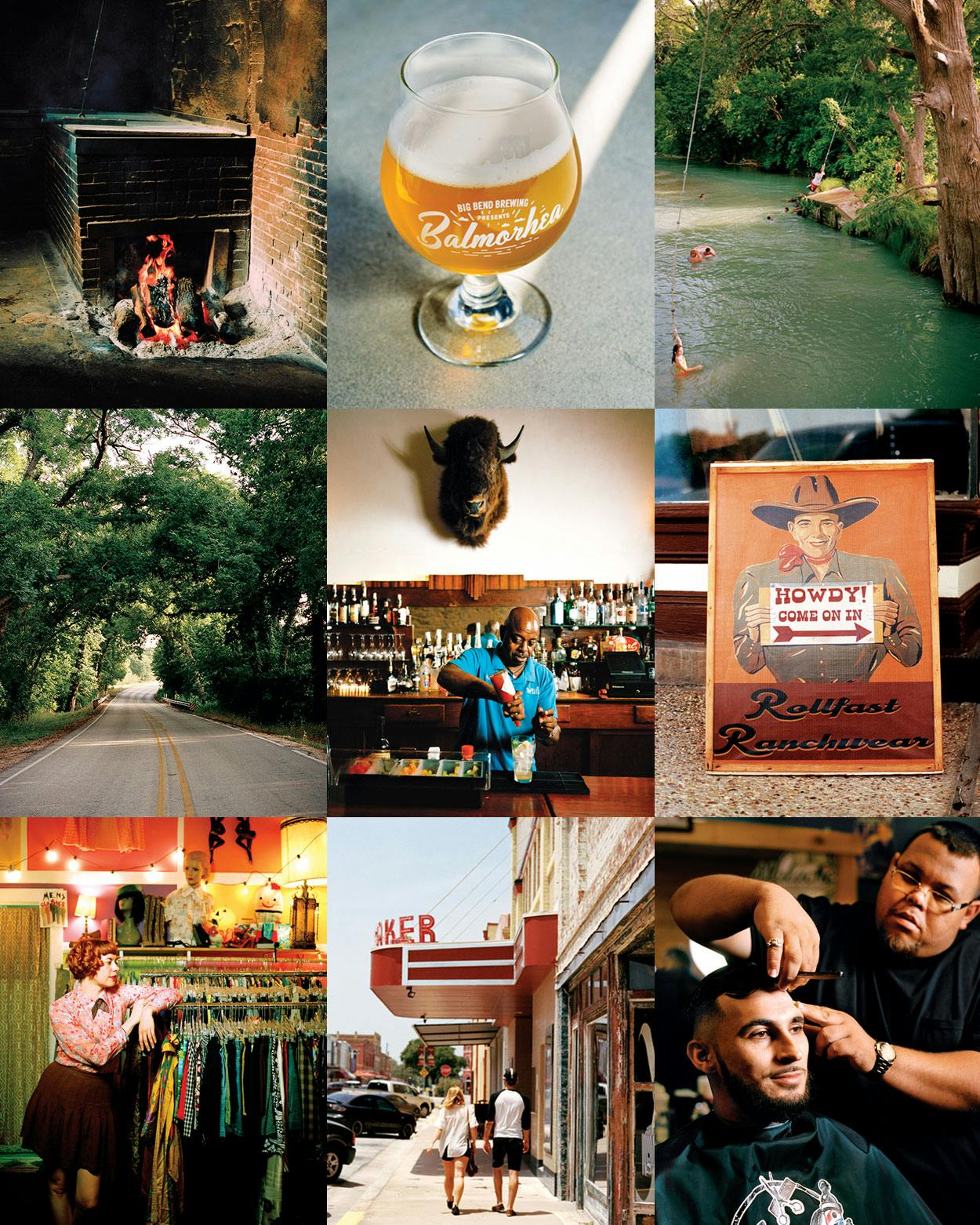

Word of their success got out, and others followed. A couple of the Platts’ friends from Austin, Taylor and Austin Burge, opened Chaparral Coffee, for which another friend, Dayna Humbert, supplied the pastries. A Whole Foods buddy, French-trained chef Sutton Van Gunten, opened Market Street Cafe and Apothecary. Next to come was Lockhart Bistro, opened by Mumbai-born chef Parind Vora. Soon the Caracara Brewing Company, started by Mike Mann, a University of Texas at Austin alum, set up shop, as did bars aplenty. Lockhart native Ronda Reagan opened up one of these watering holes, the Pearl, renovating a Victorian building to house her upscale cocktail lounge.

It’s not that today’s downtown Lockhart is all hip restaurants and bars. It still retains its real estate, insurance, and law offices. There’s the Dr. Eugene Clark Library—built in 1899, it is the oldest continuously operating establishment of its kind in Texas. There remain about a dozen churches within a few blocks of the courthouse. And as with many other small towns, Lockhart had already repurposed its former 1920s movie palace. The Gaslight-Baker Theatre stages plays, vaudeville, and variety shows.

Yet in the past few years the town has undergone a striking transformation, something that longtime locals are still taking stock of.

In June a new restaurant, the Culinary Room, held its grand opening. Housed in a handsome three-story 1898 red-brick building on the square, it offers artisanal cheeses and charcuterie, serves craft beer and wine, and hosts chef-taught cooking classes. Save for the architecture, it’s the sort of business you’d expect to find in Houston’s River Oaks or Dallas’s Park Cities. On the town’s bustling Facebook page, long-term Lockhart resident James Bliss, a 45-year-old electrical contractor who lives five blocks from the courthouse, claimed he had a bit of an epiphany when he attended the grand opening. “New and different don’t mean scary and bad, it just means different,” he wrote, though he admitted some uneasiness. “As I walked around the store I realized that I didn’t know anyone there. It almost made me feel like an outsider.”

Robert Parker, a 45-year-old IT architect who lives in nearby McMahan, chimed in. “Get ready for more weirdos, hippies, artists, musicians and freaks in Lockhart because they sure as hell can’t live in Austin anymore,” he opined. “On balance that’s probably a good thing, but change like we’ve never seen is coming and coming rapidly due to the economic conditions just to the north of us.”

Just shy of three years ago, in the pages of this magazine, I wrote an article on the state’s frenzied real estate boom, titled “Can You Afford to Live Here?” To try to ascertain what skyrocketing home prices were doing to our biggest cities, and to the folks living there, I spent a week probing the likes of Houston, San Antonio, Austin, and Dallas. My conclusion wasn’t particularly optimistic. “My road trip made me realize that our cities are getting denser and more vibrant, but I worry that the cost is unsustainable,” I wrote. “Home prices and rents are heading nowhere but up. New affordable housing is in short supply. Incomes are flatlining or trending down. When it comes to owning a home in Texas, I’m reminded of that song by James McMurtry: we can’t make it here anymore.”

Little did I know at the time that the “economic conditions” burdening the citizens of our cities were inspiring a renaissance in other parts of Texas—namely, in small towns. In many ways, that shift is counterintuitive. Though many Texans still regard our state as having a rural sensibility, we became city slickers long ago. In 1910 roughly 24 percent of the Texas population resided in urban areas; a century later that number had jumped to 85 percent.

And much like elsewhere in the country, our younger generations are especially drawn to the kinds of amenities offered by cities. From my article three years ago: “According to a 2014 Nielsen survey, 62 percent of millennials prefer walkable urban environments, which reverses a ninety-year-old trend favoring the burbs over cities. That same survey found that Austin led the nation in the percentage of millennials who favor a ‘conscious, creative environment,’ with Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth also in the top ten.”

The problem, of course, is that this idealized urban lifestyle is out of reach for most. The culprits? “Student loan debt, wage stagnation, rising rents, insurance costs, and the lingering aftermath of the Great Recession, which many millennials ran right into at a key career stage,” says Jason Dorsey, the president of the Center for Generational Kinetics, an Austin-based research and marketing strategy firm that tracks social trends among millennials and Generation Z.

These economic burdens, combined with soaring real estate prices, have meant that many have started looking farther afield for places to settle: according to Zillow, the median home value in Austin is now $346,000; in Lockhart, it is $148,000. And it’s not just millennials; folks of all stripes have found that small towns are a land of opportunity. “Employees, office space, and additional resources are often less expensive in nonurban areas, often making it more cost-efficient to start and build a business,” Dorsey says.

In fact, many small towns are ripe for rejuvenation. The industries that once sustained rural communities have been in a gradual, inevitable decline, creating a vacuum. “While it’s [only] an emerging trend now, we do think that smaller towns, particularly those strategically close to cities, have the ability to attract and keep young entrepreneurs as they build their businesses,” Dorsey says.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, this trend has also corresponded with the rise of Waco’s favorite son and daughter, Chip and Joanna Gaines, whose reality show Fixer Upper was nothing short of a revelation for viewers dealing with daunting real estate markets in metropolitan areas. For many, watching the Gaineses’ dramatic home renovations, completed for a fraction of what you’d pay in the city, felt like wish fulfillment. And some of those viewers actually decided to chase the dream.

So this summer I embarked on another road trip, this time striking out for the hamlets of Brenham, Alpine, and Lockhart—towns where the rural renaissance is well underway—to see for myself how these shifts are playing out. I wanted to know who these people are. In what ways are they changing the towns they’ve descended upon? And what do locals make of their arrival?

To those of us raised on Blue Bell commercials, Brenham and the surrounding countryside have long represented a Texas Shangri-la, a land filled with tin-roofed farmhouses where kindly grandmothers step out onto the porch and holler for us to come on home. We’d happily do so, of course, trotting through pastures shaded by live oaks and pecans, while Longhorns obliviously stamped bluebonnets and lightning bugs flickered overhead. We’d pass by several family homesteads, including one dating back to Stephen F. Austin’s Old Three Hundred colony, and upon arrival we’d be served a bowl of butter-pecan ice cream.

You might have expected some stiff resistance to these incursions of new folks and their fancy ideas. I certainly did.

Of course, that fantasy hasn’t held up these past few years. Blue Bell’s woes are well known: the listeria crisis of 2015 tarnished the image of one of Texas’s most beloved brands and visited real economic consequences on the town. Two thirds of the company’s workforce was either laid off or furloughed, and the plant in Brenham, which once hosted 225,000 visitors a year on ticketed tours, was temporarily shut down. It’s hard to overstate the effect this disaster had on the town. It bordered on a full-blown existential crisis.

And yet, against all odds, Brenham’s downtown is thriving, perhaps as never before. Once placid and puritanical, it is now merry with wine, beer, and song. Hip murals blanket the walls of several edifices. The dining scene has been upgraded. And much of that development was fostered by Brad and Jenny Stufflebeam.

Brenham’s downtown renaissance began, in part, with a seed planted in the lush and rolling Washington County soil. Literally. Sitting in the Stufflebeams’ laid-back biergarten, serenaded by birdsong and an alt-country soundtrack, I heard the whole story from Brad, delivered in his good-natured growl of a voice.

Brad, 47, grew up in the Dallas burbs and has been running from them ever since. After a stint in the Navy in the early nineties, during which he studied horticulture in his limited spare time, he returned home in 1993 and married Jenny, his high school sweetheart. They spent their nest egg on Greenhouse Gardens, an organic plant nursery in McKinney, which was then still somewhat out in the country.

Such was not to last. Dallas sprawl was on the march, and when a Home Depot popped up across the highway, the Stufflebeams looked to get out. They arrived in the Brenham area in 2004 and settled on 22 acres of prime Washington County farmland. They started a community supported agriculture program, which allows farmers to sell their produce to urbanites via a subscription service. Brad approached neighboring farmers and persuaded them to join him; soon, a syndicate of twelve area farms was providing roughly 360 Houston families and a handful of restaurants with farm-to-table eggs, vegetables, cheeses, honey, poultry, beef, and pork.

They were reviving an old way of life. Long ago the Brenham area served as Houston’s breadbasket. On Friday evenings the rough road heading southeast out of Brenham, toward Houston (pretty much today’s Highway 290), was lined with a steady stream of rumbling wagons driven by mostly German “truck farmers,” bringing their produce to sell in Houston’s teeming downtown Market Square. “At first my neighbors didn’t understand the CSA thing,” Brad says. “And I would just tell ’em, ‘It’s truck farming. I am going into Houston and into neighborhoods and delivering food to people down there.’ And they would be like, ‘Oh yeah! That’s what my grandfather used to do!’ ”

In 2013 the Stufflebeams made the leap to brick-and-mortar, leasing a late nineteenth century downtown building and opening an organic grocery. Home Sweet Farm, they named it. “It was time to put our heart in the community we live in instead of feeding people in Houston,” Brad says. “And Brenham kinda needed a kick in the spirit.”

Did it ever.

“When the Blue Bell thing happened, [the city] realized they were putting too many eggs in one basket,” Brad says. “They saw a twenty percent drop in their tourism, and they realized other things were important for the Brenham experience as well.”

To lure more customers, the Stufflebeams threw six Texas craft beer taps on the wall. Business boomed. Home Sweet Farm did well enough for Brad and Jenny to expand into two adjacent buildings, and then they filled in the gap between the structures with a stage improvised from an old loading dock. They wheeled in some picnic tables, and—voilà—they were now the proud owners of a small music venue and biergarten. “Everybody came out of the woodwork,” Brad says. “We’ll squeeze in 150 people on a weekend night.”

As in Lockhart, one success story created a domino effect, and other new mom-and-pop businesses followed. There’s Las Americas, a pan-Latin restaurant. There’s also 96 West, a New American comfort-food place offering tapas alongside burgers. And amid much hoopla from the barbecue cognoscenti, Truth Barbecue popped up on Highway 290 west of town.

Later, Brad walked me around the corner to the Brazos Valley Brewing Company (along the way he showed me a line of small warehouses slated to become art galleries), where I retired to the patio with owner Josh Bass. Josh laid out the strategic benefits of Brenham’s location. He’d considered Fredericksburg and was briefly enticed by the tourism it attracted, but why put a brewery way out there when you could put one in Brenham, close to two of the state’s thirstiest college towns (Austin and College Station) and also the state’s largest city, Houston? “Brenham also had that vibe going for it,” he says. If the crowds at the bar that afternoon were any indication, the bet paid off.

As I looked around the square, I realized that Brenham is changing, but not so much that you wouldn’t recognize it—the Blue Bell plant has even rebounded. The town is just wearing more fashionable clothes these days. “We’re embracing the modern of today but still cherishing the heritage,” Brad told me that afternoon. And he let me in on his next big idea. He thinks Brenham could become a music destination. “We’d catch all these artists between Austin and Houston. It’d be a real, authentic thing. Be unplugged, close to the people.”

That’s about the way Brenham feels now: like a city unplugged. Perhaps a different vision from the Blue Bell commercials we grew up with but an enticing version of the Texas dream nonetheless. “Candy Land for Texas,” Brad terms the area. “The Texas good life, Houston’s Hill Country.”

Nobody ever put to paper a more detailed and specific depiction of the Texas dream than Putnam-bred Larry L. King, the author, journalist, and playwright most widely known for The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. In a 1975 essay titled “Playing Cowboy,” he described his Texan dream as an “improbable corner of paradise.” It would be centered on a “rustic, rambling ranch house” with a “clear-singing creek nearby,” and that burbling brook would be shaded by groves of trees “under which, possibly, the Sons of the Pioneers will play perpetual string-band concerts.” All of this, King wrote, would be located “about one easy hour out of Austin” and “exactly six miles from a tiny, unnamed town looking remarkably like what Walt Disney would have built for a cheery, heart-tugging Texas-based story happening about 1940.”

If Brenham and Lockhart jibe with King’s vision improbably well, Alpine, way out in West Texas, is in a league all its own. The town’s unofficial new slogan, “Austin may be weird, but Alpine is far out,” was borne out for me late one night when I was on a starlit downtown stroll. I suddenly found myself in the company of a twelve-point mule deer buck. We were the only two living souls out and about at that hour, and I found the clip-clop of his hooves on the pavement reassuring.

Many who yearn for the kind of isolation offered by this part of the state cite Marfa as their first choice. The trouble with that plan is that even with all its hipster cred, Marfa continues to shed year-round population. Driven by the wartime economy, its populace peaked in 1945, at around 5,000. By 1990 it was half that amount, and the gradual decline has continued in the decades since. By 2017 the population was less than 1,800. So, although Marfa is gaining cachet, it is losing people, thanks to second-home buyers, short-term-rental profiteers, and speculators. The working class has been priced out to Alpine and Fort Davis or away from the area entirely.

By contrast, Alpine has held relatively steady, hovering around 5,000 to 6,000 people since 1950. Marfa is indubitably a très chic oasis of cool, but it is becoming less an actual town than an amusement park for the well-heeled. “High school sweethearts have to move away from there now,” says Harry Mois, the owner of Harry’s Tinaja bar, in Alpine. “There is something not right about that.”

Mois came to Alpine in 1999, after adventures in the French Marquesas Islands and Colorado. He was just passing through but found the open space and clean air he craved, and he ended up staying. He also discovered that Alpine was developing an interesting cultural scene all its own.

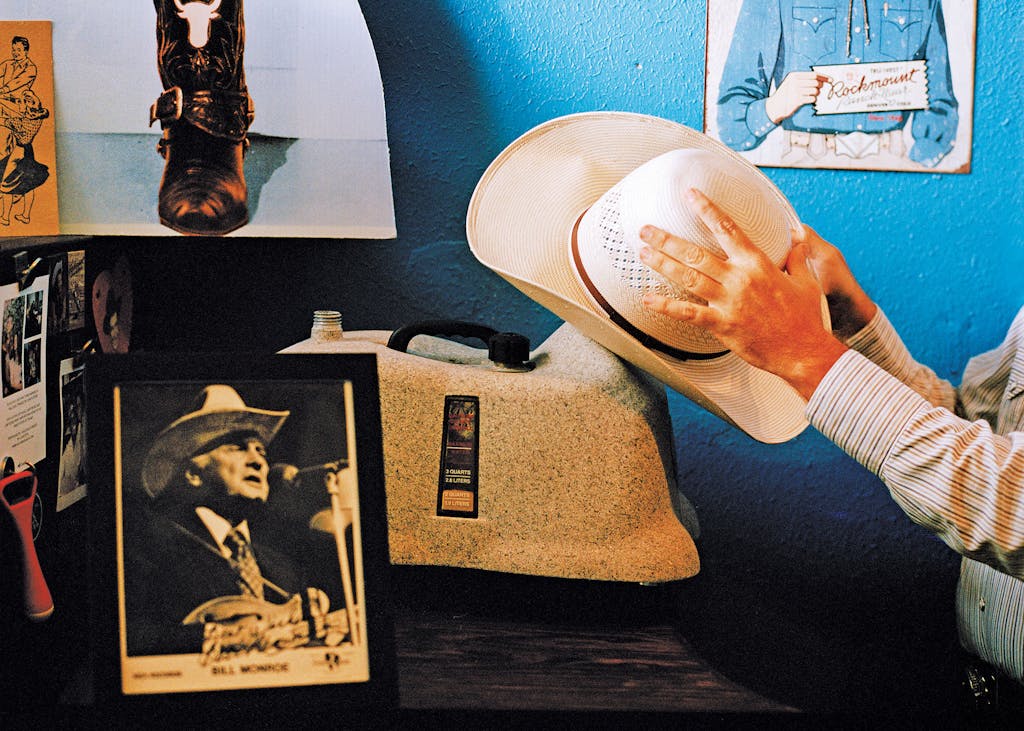

Though it’s still a rugged town, Alpine has its frills. There’s the Maverick Inn, an old motel made over in a toned-down Hotel San José style. There’s a boutique hotel in the heart of downtown, the ninety-year-old Holland Hotel, complete with a fine-dining establishment on the ground floor. There’s the java spot Plaine (an anagram for Alpine), which shares a building with a laundromat—and an independent vinyl store, RingTail Records. As any hip small town must, Alpine also produces its own beer. Big Bend Brewing Co.—“The Beer From Out Here”—launched six years ago.

The food truck park, along the main drag on Holland Avenue, is ringed by muraled walls, and the fare is surprisingly exotic. That’s where Greg Green runs the Smokin’ Cuban. He grew up here and moved back in 2015 to open the food truck with Emma Diamond, a friend whose background was in Cuban-infused South Florida cooking. “And mine was spent in Texas cooking barbecue, so we fused the two and became the Smokin’ Cuban!” Green says.

There’s a new-and-used bookstore, Front Street Books, whose owner, Jean Hardy-Pittman (she has since retired), told me she was so smitten with Alpine’s flora—spiky Spanish daggers and spindly ocotillos—that she ditched her professional life in Houston to be closer to them.

In Alpine, of course, you are leaving behind the creature comforts most Texans take for granted; the nearest Whataburger and H-E-B are a 143-mile trip to Odessa. It’s a smidge too remote for my own dispositions, but I could still understand the allure. One afternoon I met artist Tom Curry, who moved here in 1993 because he was attracted to its remoteness and the unspoiled frontier. Of course, there’s also the added bonus of proximity to the spectacular scenery of Big Bend. And then there are those amazing cerulean skies, bright blue by day and a river of stars by night. It’s enough to give you pause and make you wonder: is it time I consider leaving life in the city behind?

Lockhart native Bobby Herzog, 34, grew up with conflicting visions of his hometown. There were the stories from the old folks, who reminisced about a lively downtown, bustling with people shoulder to shoulder on the weekends. And then there was the reality of his youth: other than law and real estate offices and barbershops, the square was dead. Well, not quite. “You could come downtown at night to watch the bats fly out of the abandoned buildings,” he recalls.

Today Herzog, who manages a furniture store on the square, recalls the trepidation his fellow natives felt at first about the new “kids” in town. “Lockhart is a friendly community that just wasn’t used to change,” he says.

Still, the speed of that change concerned him, and to help the new and the old blend in harmony, he took the helm of the Downtown Business Association in January 2017. “At times I was called crazy to mix so many different personalities in to one small organization, but I can tell you that there is no other small town in Texas that has this many creative minds that all hold their town dear to them,” he says.

You might have expected some stiff resistance to these incursions of new folks and their fancy ideas. I certainly did. As Dorsey, the millennial expert, puts it, “Some smaller towns and communities still have a good old boys network that can be tough to break into or work around.”

But I found quite the opposite to be true. Sure, there was the inevitable grumbling. Herzog told me that in Lockhart he would hear occasional cracks like “The hipsters are taking over” or “Go back to Austin,” but he believes these were far more bark than bite. All across town, there are signs that old and new have joined forces in unlikely ways. When I asked Richard Platt about this, he told me about the scene at Load Off Fanny’s, the music venue and dive bar that he and Miranda and their partners recently opened. “On a Friday night it’s not uncommon to see young metal kids sitting at the bar with diesel mechanics and ranch hands.”

Judging from a sustained debate I read on Lockhart’s Facebook page, the town’s main source of distress is the seemingly inevitable march of suburbia southward from Austin.

In Brenham, where suburbs are not an imminent threat, the blowback is more about what the late Australian art critic Robert Hughes called “the shock of the new.” When the Texas Arts and Music Festival, which enters its third year this October, commissioned a series of modern murals across several downtown buildings, there was some peevish reaction. In the comments section of an article announcing the murals, someone called them ugly: “They’re all very new-age and ‘Austin-ish’ and clash with the traditional atmosphere of Downtown. While the artwork is very high quality, these types of murals are better suited for Austin than Downtown Brenham.”

But most of the commenters echoed the sentiments of one person who identified as a native who had left Brenham and returned home to raise a family. The murals were just the ticket to help Brenham continue to thrive, they contended: “We always hear that we can’t keep Brenham kids in Brenham. Well if you want to get college graduates from Brenham, back to Brenham, you have to give them something to come back to. I love the scene in downtown. It’s got great places to hang out and have a beer that are cool and family friendly. This town literally had nothing like that when I was growing up here throughout the 80’s and 90’s.”

When I spoke to Jennifer Phillips, who works for the Washington County Convention and Visitors Bureau, she said she doesn’t like all of the edgy murals, but she welcomes their presence just the same: “In order for our little town to thrive, things can’t continue to stay the same.”

So, let’s recap: there’s affordability, a slower pace of life, top-shelf food and culture, and a welcoming, friendly community. During my travels, I found myself—a near-lifelong Houston resident—increasingly bewitched by the notion of small-town life. I began dreaming, to paraphrase Guy Clark’s “L.A. Freeway,” of packing up the dishes, making note of all good wishes, saying adiós to all this concrete, and getting me some dirt-road backstreets.

On a warm April evening, I strolled around downtown Lockhart and watched young mothers chatting and sipping coffee at sidewalk cafes while their toddlers played with dollhouses and Matchbox cars on the sidewalk. I could hear sparrows cheeping, even a songbird whistling away.

Who needs a teeming metropolis when you can re-create the best parts of it at a fraction of the price and about half the stress?

I pictured myself building a new life here with my wife and daughter, sliding right into a community of like-minded friends, maybe even taking a leatherworking class one weekend at Lockhart Arts and Craft, enjoying the secular fellowship.

At my age, racing up to fifty, there is just as much push from the big cities as there is a pull from these towns. Houston is not as cheap as it used to be; once-affordable neighborhoods like Montrose are now downright expensive. There’s the never-ending grind of the city’s continuous evolution, a process that largely involves tearing down all its landmark homes and legacy businesses and replacing them with luxury apartment buildings, anonymous townhomes, and chain establishments. I now get turned around in neighborhoods I’ve been steeped in for a half century. My dad’s boyhood home, in West University Place; my daughter’s first home, near Rice University; the house in which I was conceived, in Montrose; my great-grandfather’s home, near the Galleria—all have been leveled and replaced with things that are bigger, uglier, and costlier.

And it wasn’t just the rustic life I was longing for. Each of these towns was starting to put me in mind of little country places I’d tramped through in England during my wanderlust years, a version of a Cotswolds village. It felt like a place where I could finally exhale.

Sara Barr, the 33-year-old co-owner of Lockhart Arts and Craft, says I am not the first to hazard such comparisons: she says she’s heard similar sentiments from French, German, Scottish, Irish, and Australian tourists. “They’ll say stuff like, ‘This reminds me so much of this certain neighborhood of Paris’ or ‘This is just like a little town outside Berlin.’ ”

Richard Platt also sees the European comparison as apt. Lockhart’s square, he says, is built around the works of a group of local craftsmen sharing their wares. He and his family live a few blocks away, and he says he seldom has to make the drive out to Walmart. “There is [often] a viable alternative made by someone I know right here in town,” he says.

A typical day for him starts with a nice cup of coffee and a fresh, scratch-baked pastry. A modernized Texas comfort food lunch at the Market Street Cafe comes next, and then he starts tossing pies at Loop & Lil’s. When he’s finished there, it’s off to a quick beer at Caracara and then maybe a stroll through an art gallery or a play at Gaslight-Baker. The point is, there is no mandatory driving, there are no generic national chains, everybody is their own boss, and they are all nice to one another. “We have really just created our own microeconomy right here on the square, full of the life and culture that leads most people to the big cities in the first place,” he says. And they have done so, he adds, “with all the small-town feel of home.

“The small towns in Texas seem to be the only places left where people in my generation have a chance to start something from scratch with little money to invest, as long as they work hard and are skilled at what they do.”

As I sat on a downtown bench alongside Barr, an Austin native, she lamented the intensifying pace of the city. She says there used to be an ineffable simplicity to Austin: “You could walk down the street in certain parts of town and see people you knew, always run into your friends at the Broken Spoke or Ginny’s, and lots of places still felt just like walking into a friend’s house.” Less so today, she says. “The idea of simplicity appeals to me a lot, being able to actually just walk around town and go to businesses where you know the owners because they’re there all the time and they’re friendly and welcoming.”

It harks back to what the experts say about millennials, how they want walkable urban environments. Maybe the only places they can find those today are in spots like Lockhart, that minor triumph of urbanity. Who needs a teeming metropolis when you can re-create the best parts of it at a fraction of the price and about half the stress? Such places are like a distilled version of the city, leaving only the stuff you love.

Or, as Barr puts it, “This is the Austin I’ve always wanted.”