What will happen to the girls and women deported from the U.S. to Central America? Many fear the answer.

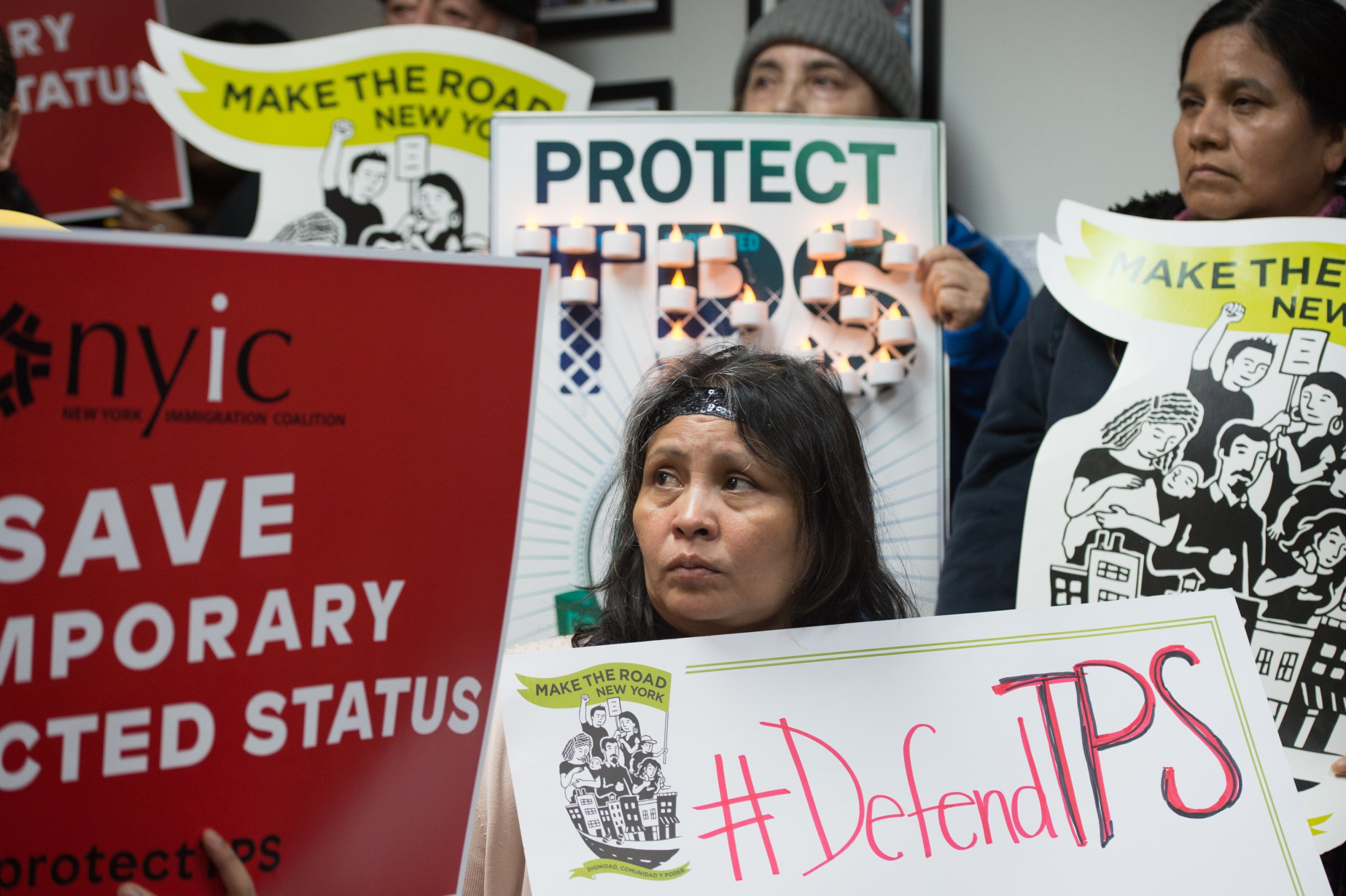

The Trump administration said last week that, by September 2019, it will deport 200,000 Salvadoran immigrants who have been allowed to stay and work legally in the U.S. thanks to temporary protected status, or TPS. Nicaraguans, too, will only receive protected status for another year, and Hondurans could be next to face deportation.

Women and girls, though, are in the most danger. Stripped of TPS, they now face not only the fear of family separation, but also the prospect of returning to a country which has one of the highest rates of violent homicide of women in the world. Deportation could be a death sentence.

Violence against women is a major concern in Central America. The MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs operating in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras are considered the most violent criminal groups in the world. Rape is used to intimidate, to demonstrate loyalty and to claim girls as gang property. The International Crisis Group, for example, cited a former Barrio 18 female gange member who said, "It is unbelievable how violent they [gang members] can get ... how they treat their wives and mothers."

El Salvador was second only to Syria in the rate of violent female deaths between 2010 and 2015. And every 18 hours, a woman is killed in the Central American country. "In El Salvador, women are terrified, especially young women," says Vilma Vazquez, founder of Las Dignas, a feminist association in El Salvador. "We know we're going out but we do not know if we are going to get back home alive." If pregnancy results from rape, a woman in El Salvador does not have the option to terminate the pregnancy. As the Fuller Project for International Reporting reported last year, El Salvador has one of the strictest anti-abortion laws in the world.

Immigrants who flee sexual violence in their home countries can apply for a special form of asylum in the U.S., but it is rarely granted. "If you go through traumatic violence it's difficult to disclose to government officials especially after the journey," says Cecilia Muñoz, former policy advisor to President Barack Obama and now vice president at the New America Foundation. "To the extent that it comes out, it's in the application for asylum, if the woman is well-represented."

The vast majority of the Salvadoran women who face deportation are active contributors to the U.S. economy. Eighty-two percent of the Salvadoran, Honduran and Nicaraguan women interviewed in a survey by the University of Kansas said they were part of the workforce, and more than two-thirds reported paying social security taxes. In a statement to the National TPS Alliance, Vanessa Velasco, a Salvadoran TPS holder from Northern California, said "It is embarrassing for this country to not even consider the real contributions our community has made for decades."

Many are also raising questions about the economic ripple effects of deportations, both on U.S. families and on the Salvadoran economy. The most common form of employment for women from Central America with TPS is child care. In 2017, Salvadoran workers in the U.S. sent more than $4 billion to families in El Salvador.

Amazingly, women under threat of deportation remain hopeful. "Even if it is devastating for my family, this situation also gives me the strength to fight," Veronica Lagunas, a TPS holder in San Fernando Valley California, told the National TPS Alliance. "We will not sit silently and await deportation. We will continue to find allies … We have no choice, and we are ready."

Xanthe Scharff is executive director and Dánae Vilchez is a Nicaragua-based reporting fellow for The Fuller Project for International Reporting, a journalism team that reports globally on women. This op-ed is part of an ongoing series on women, security and peace-building, supported by Women, War & Peace and the Fuller Project for International Reporting.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.