Part of the problem with Pope Francis’s change to the Catechism on the legitimacy of the death penalty – a decision on which he is doubling down in the face of worldwide opposition from theologically literate Catholics – is that it fundamentally misconstrues the role of a catechism.

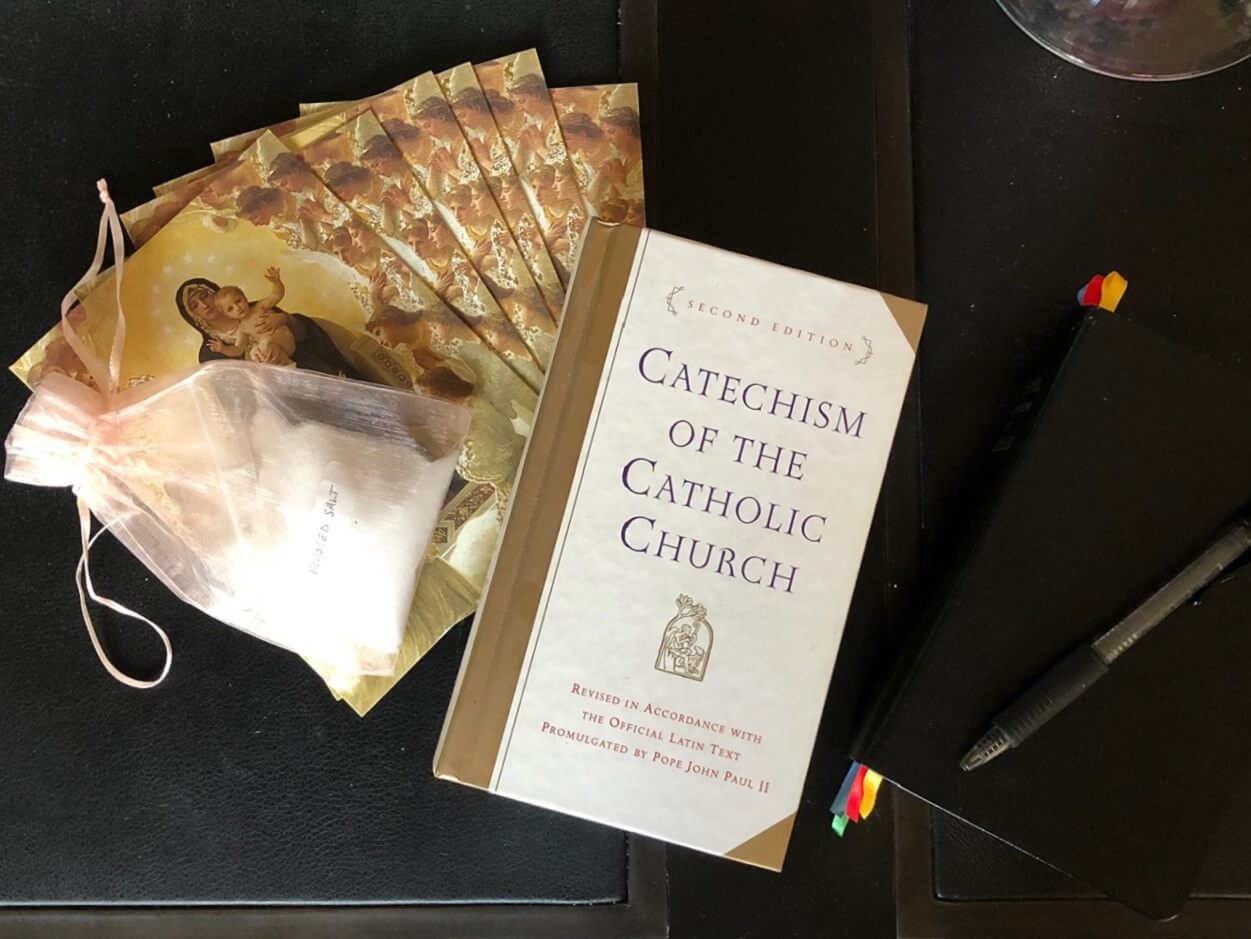

A catechism is not, and has never been seen as, an instrument for introducing new doctrine or for pushing forward “development of doctrine.” A catechism’s function is far humbler than that: to pass on, simply and accurately, the pre-existing teaching of the Church. Its value consists in a pedagogically well organized restatement of what the Magisterium authoritatively teaches. As John Paul II reminded us in promulgating the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the individual statements of this book have only such authority as their sources in Scripture, Tradition, and the Magisterium already possess. Perhaps one could say a statement’s being in the Catechism lends it some additional “clout,” but its intrinsic authoritativeness is measured by other means.

A catechism is a convenient guide to what the Church teaches; it is not so much magisterial as it is a synopsis of the Magisterium. A good catechism is like a clean, smooth, untainted mirror that reflects the content of the Catholic Faith. A poor catechism (like the infamous 1966 Dutch Catechism that caused so much trouble after the Council) is, on the contrary, a cloudy, scratched, bent, or chipped mirror that does not lucidly reflect the Faith.

How many catechisms were published prior to the Second Vatican Council, in all languages? Has anyone ever counted? Two hundred fifty? Five hundred? One thousand? Even more? Now think of it: every one of these catechisms would have stated somewhere that the death penalty is legitimate [i]. Along comes Francis, and by a stroke of the papal pen (I had almost said magic wand), suddenly, thousands of other catechisms are falsified on a point of no small significance. Think of it: contrary to every catechism from the first one published in Germany in the 16th century down to the era of John XXIII, the “new new” Catechism speaks alone. This, I submit, is a sign of megalomania, of a man disconnected from his office and from reality.

It cannot be other than cause for great concern when a catechism is exploited as a delivery system for new ideas, which in turn are sourced only to a single address made by the pope to a curia-sponsored gathering – in other words, an occasion and a context admitted by all to be of little weight. This, by the way, is quite apart from the question of the contradiction between what the pope said in that address and what has always been taught by his predecessors, whom he recently dismissed as “having ignored the primacy of mercy over justice.” Commenting on this astonishingly arrogant statement, Fr. John Hunwicke said: “Dear dear dear. Pretty nasty, that. What silly fellows they must all have been to make such an elementary error. But Don’t Worry. All, apparently, can be explained by ‘development’.” Never mind that in dismissing all of them at once, he is undermining his own authority.

Francis’s change to the new Catechism prompts another train of thought. What, after all, is the value of this very catechism?

Years ago, it was pointed out to me that the Catechism omits mention of the New Testament teaching on the headship of the husband in marriage – despite the fact that this teaching is given multiple times in the New Testament, with a clarity greater than that of many other doctrines we typically consider crystal-clear, and despite the fact that the doctrine was often repeated by the Magisterium, at least up through Pius XI’s classic encyclical Casti Connubii, where it was given a winsome and nuanced interpretation. Why was this aspect of Christian teaching on marriage omitted in what was purported to be a trustworthy guide to the Catholic Faith? Oh, feminism and things like that. How do we know? Because the Catechism dances around the question, cites N.T. texts adjacent to the “offensive” ones, and does all that it can to avoid bringing up the subject.

Should this bother us? Absolutely. If we discover only one important teaching that is missing from a catechism by design and not by editorial oversight, then in principle the reliability of this catechism is called into question. It is seen to be under the curse of political correctness to some extent – how much would be difficult to say without exhaustive study, but the seed of doubt is already planted. We start to feel that this guide may not, after all, be entirely trustworthy [ii].

Then one remembers how there were already changes to the new Catechism almost before its ink was dry. The second edition had a few substantive changes, including one already on the death penalty to reflect how John Paul II was thinking about it. Another change, on homosexual inclinations, was admittedly a significant improvement – and yet one wonders why the original editorial team, headed by Christoph Cardinal Schönborn, would have expressed the point so badly to begin with. This doesn’t inspire confidence in the drafters.

Since at least Dignitatis Humanae, there’s been a tendency to think doctrine is malleable, according to the whims of the reigning pontiff or the consensus of bien pensant theologians. Back in the day, conservative Catholics tried to do this with social doctrine when they refused to accept John Paul II’s critique of capitalism in Centesimus Annus. Now it’s the liberals’ turn in the limelight, railing against the death penalty, but there’s been a general tendency for just about every modern school of Catholic thought to play this game. The ultimate source of this tendency is poor philosophy and even poorer theology, a refusal to acknowledge, on the one hand, that truth is a correspondence between thought and reality and, on the other, that the content of our faith is divinely revealed to us and is not subject to a process of mutation and evolution, no matter how many centuries we spend pondering its inexhaustible truth.

A friend recounted to me how a devotee of Hans Urs von Balthasar, a dazzling synthesizer of orthodoxy and modernism who could deceive even the elect, once told him that Balthasar’s concept of what our Lord did during His time in the grave on Holy Saturday couldn’t get into the Catechism right now, because it hadn’t been “received” yet, but in time it might. According to this notion of revelation, a theologian gets a brilliant idea; it catches on with other theologians; and after a time, lo and behold!, we have a new doctrine. Or perhaps just a “deeper grasp” of a doctrine, albeit one that actually contradicts just about everything that had been held about it up till now. One is reminded of the eulogy pronounced upon Teilhard de Chardin by one of his disciples, Henri Rambaud: “He was already thinking then what the Church did not yet know she would be thinking shortly. … Instead of being in agreement with the Church of today, he is in agreement with the Church of tomorrow” [iii].

If any of this were true, then nothing in the Faith would ever be certain; our house would be built on shifting sand, not solid rock. We know this to be false, because all twenty ecumenical councils prior to the sui generis experiment of Vatican II solemnly declared, in the name of God, binding dogmas of truth and condemnations of errors. One who walks down the path of novelty is not deepening our collective grasp of truth, but simply departing from the Catholic Faith. As the ancient “Athanasian” Creed thunders: Quicumque vult salvus esse, ante omnia opus est, ut teneat catholicam fidem: quam nisi quisque integram inviolatamque servaverit, absque dubio in aeternum peribit. “Whoever wishes to be saved must, above all, keep the Catholic faith; for unless a person keeps this faith whole and entire, he will undoubtedly be lost forever.”

As good as much of it is, I never really thought, even in the nineties, that the new Catechism of the Catholic Church was the “be-all and end-all.” One might have felt ashamed to admit such misgivings back in the misty-eyed days of its promulgation when, after decades of doctrinal chaos and almost no guidance from Rome at the catechetical level, the Catechism came forth like Lazarus from the tomb. And perhaps it was something of a miracle in the early nineties.

In any case, that was then, and this is now. As a friend of mine soberly put it:

The CCC was a lukewarm response, made a quarter of a century too late, to the capillary diffusion of endless heretical catechisms throughout the Church, to which the papacy had made no effective response whatsoever. After 50 years of eroding the foundations of all doctrine by its silence and complicity, the papacy has shifted gears ever so slightly to eroding them via positiva by its own proclamations.

What Pope Francis has done will backfire, like the hubris of the protagonist in a Greek tragedy. For he has given us a new and, I would say, pressing invitation to chuck the new Catechism, that “mirror of the reigning Narcissus” and instrument of social change, into the trash bin and reach instead for the Catechism of the Council of Trent, the Baltimore Catechism, or dozens of other books that are more accurate, comprehensive, and unquestionably Catholic guides to what the Church has believed and taught in her 2,000-year pilgrimage through this vale of tears.

The uniform testimony of traditional Catholic catechisms is an undimmed light amid the doctrinal darkness besetting the Church. As Whispers of Restoration reminds us:

Because Christ committed to His Church a single, “defined body of doctrine, applicable to all times and all men,” one should expect to peruse not only decades, but centuries of Catholic catechisms and theological manuals and discover harmonious agreement and unbroken continuity on all matters of faith and morals. And find it one can; for when Catholic bishops spread throughout the world and across time give unified voice to their teaching office in catechisms approved by them, this is an authentic expression of the universal ordinary magisterium, an organ of infallibility, and an effective antidote in our own time against the erroneous notion (long since condemned by the Church) that dogma can evolve.

And in another article (most highly recommended) at the same site:

For the average Catholic seeking to learn this Faith and hand it on to others in an error-plagued age, few things will bear this out like the reading of traditional catechisms. The continuity found in such study is both clear and compelling, and little wonder; for it illustrates the teaching of the universal ordinary magisterium.

Whispers of Restoration has made available, for free download, twenty traditional catechisms and three additional reference works. All such catechisms bear witness to the perpetual faith of the Catholic Church on such momentous issue as these:

- that adultery may never be countenanced;

- that the sacraments may not be received by anyone living in an objectively disordered situation without repentance and intention of avoiding sin;

- that the husband is the head of the family (with all the responsibilities that entails), and the wife owes him lawful and rational obedience;

- that the State has divine authority to pronounce the death penalty;

- that Christ enjoyed the beatific vision throughout His earthly life, including in His most bitter Passion;

- that Christ’s descent into Hell was one of victory and liberation, not a continuation of His expiatory suffering.

What the confusion of our day requires, and what the much-touted dignity of man deserves, is not the new and improved Catholicism of the ever newer Catechism, but the illuminating Faith of our fathers, “the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3).

[i] The website Whispers of Restoration helpfully provides many examples of this very point.

[ii] As I have argued here and elsewhere, the same thing can be said of the deliberate omission of 1 Cor. 11:27-29 from the new lectionary and therefore from the new liturgy in its entirety, although it was prominently present in the old liturgy and therefore constituted a part of the Church’s pre-existing liturgical tradition. Similarly, the omission of many psalm verses from the Liturgy of the Hours means that whoever follows these liturgical books no longer prays the Psalter as given by God. Such omissions, against the backdrop of a hitherto uninterrupted practice, call into question the value and legitimacy of the entire projects to which they pertain.

[iii] From the forthcoming book by Gerard Verschuuren, The Myth of an Anti-Science Church: Galileo, Darwin, Teilhard, Hawking, Dawkins (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2018), 120.