The high-wire act LSU has performed at quarterback is widening to a sidewalk, and an unconventional roster transaction helped the Tigers stay balanced.

Joe Burrow became the first graduate transfer to start at quarterback for LSU this season, and his consistency helped mask the issue that the Tigers only had two scholarship quarterbacks on the roster.

The acquisition of Burrow, a junior, from Ohio State essentially gave the LSU coaching staff a two-year window to construct a productive quarterback stable — something the football program has not had for the majority of the past decade.

Only two LSU quarterbacks have cracked the nation’s top 10 in quarterback efficiency rankings in the 12 seasons since JaMarcus Russell won the Manning Award for nation’s top quarterback. Both of those players — Danny Etling (2017) and Zach Mettenberger (2013) — transferred into the program from another college.

LSU hasn’t had much success with the elite high school quarterbacks it has recruited. Four of the six top 10-ranked quarterbacks (as ranked by 247Sports) the Tigers have signed since 2009 transferred out of the program. Russell Shephard converted to wide receiver after signing in 2009, and the jury’s still out on Myles Brennan, who is currently Burrow’s backup.

Jarrett Lee was an LSU quarterback for five years, redshirting in 2007 and staying until the bitter end in 2011.

It’s a struggle several programs across the nation share.

Since Tim Tebow left in 2009, Florida has gone through three head coaches and several starting quarterbacks until Feleipe Franks led the Gators to a 9-3 record this season.

Texas fumbled through signal-callers for nearly the same period of time, trying to replace Colt McCoy, until Sam Ehlinger led the Longhorns to a Big 12 championship appearance this season.

But after each of those program’s gaffes, Florida and Texas were able to cast their nets into the abundant recruiting pools in their own backyards.

LSU doesn’t have that luxury: Eleven of the 14 quarterbacks who have signed with LSU since 2009 went to a high school outside of Louisiana.

“(LSU’s) not in a state that has regularly produced high-level quarterbacks,” said Barton Simmons, 247Sports’ national recruiting reporter.

It begs the questions: If not Louisiana, just where do elite quarterbacks come from? And why?

The Advocate interviewed experts to answer those questions, and after compiling, mapping and analyzing each year's top-10 quarterback recruits for the past decade, the answer came down to two main traits:

• States that have long embraced 7-on-7 competitions

• Regional communities that have the access and funds for private quarterback coaching

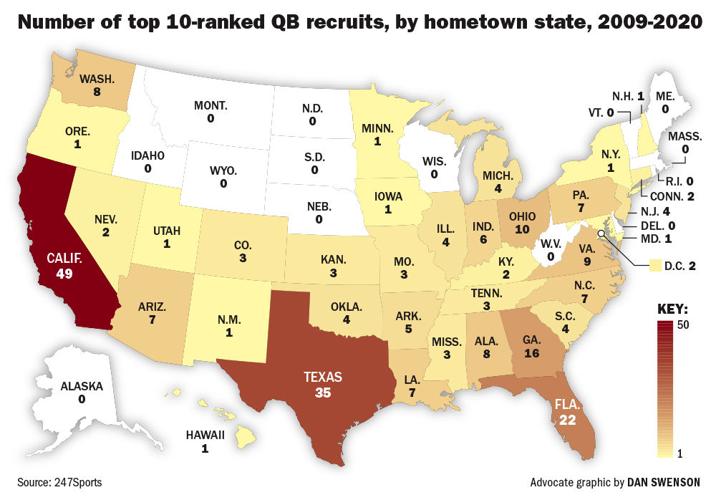

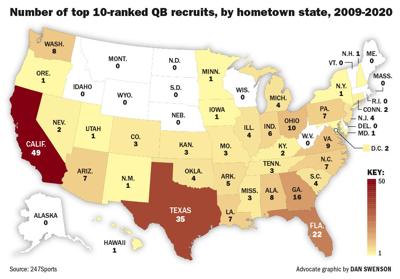

When the data is illustrated (see map), the correlation almost appears to be population-based — sort of like the House of Representatives map you’d find in a political science textbook.

But one look at New York, which has produced just one top-10 quarterback recruit since 2009, quells that theory.

The other most populous states are bountiful — California (49 top-10 recruits), Texas (35), Florida (22) — and it’s because those regions have embraced football in a way no one else has.

A high-flying revolution

For the state of Texas, the journey began two decades ago in a hotel lobby in Houston.

Dick Olin passed out the rule sheets. The Texas high school coaches flipped through the pages in the Holiday Inn off a busy highway.

The rules are commonplace today — seven players each, no linemen, no tackling, four seconds for the quarterback to throw the ball — but in 1996, Olin, the head coach of Baytown Lee, had to go all the way to the University of Illinois to obtain them.

The coaches were seeking a new way to progress their young quarterbacks in the new spread offenses that were developing, and the governing body of Texas high school athletics, the University Interscholastic League, had just passed a rule that allowed its high schools to compete in 7-on-7 games.

The variation of football was an easy way to keep their players active over the summer, and it honed the most basic skills that are necessary in a passing offense: throwing and catching.

The first 7-on-7 tournament in Texas was held that year at the University of Houston. By 1998, that group of coaches grew it into a statewide tournament.

Olin saw the benefits in his football program at Baytown Lee, which produced seven Division I quarterbacks in a row — including Iowa’s Drew Tate, who threw the Hail Mary that beat LSU 30-25 in the 2005 Capital One Bowl.

“It’s been 22 years now of throwing and catching, and you’re bound to get better,” said Olin, who retired in 2012 after 26 years of coaching. “It’s the reason for where we are today.”

The LHSAA has not sanctioned 7-on-7 in Louisiana, and high schools within the state have only began to compete independently within the past 10 years. For the most part, 7-on-7 in Louisiana has only been able to highly function on a private level — with elite athletes seeking out travel teams like the Louisiana Bootleggers, coached by former LSU safety Ryan Clark.

“I think (7-on-7) has helped the development of the position in a way that a lot of folks are hesitant to agree with,” Simmons said. “I think that the reality is, it goes hand-in-hand with quarterbacks being prepared.”

And 7-on-7 has another allure: The massive exposure it can give recruits at national events such as the Nike Opening and the Elite 11 tournaments, which are crawling annually with recruiting writers and college scouts.

Can't see video below? Click here.

Coach 'em up

The 7-on-7 variation of football is really only the first step in advanced quarterback training, said Jake Heaps, a former NFL quarterback who signed with BYU as the No. 4 pro-style quarterback in 2010.

“I think there’s a big misperception that it’s the best,” said Heaps, who said he competed in the first Scout.com tournament in Las Vegas in 2008. “If it’s done right, it can be a phenomenal tool. But there’s a lot of bad habits that can happen — especially if you don’t have a coach helping you with your decisions on the field.”

That leads to what Simmons said is the main driving force in quarterback development: private quarterback training.

Heaps, who attended Skyline High in Sammamish, Washington, said the best training he received came from his private coach, Taylor Barton — a former quarterback for the Washington Huskies.

“It’s ultimately the No. 1 thing kids can do to help their game,” said Heaps, who trains quarterbacks in Washington. “There’s an evolution of quarterbacks being groomed at an earlier age where they’re more mechanically sound and ready to play than they ever were before.”

And with the proliferation of complicated college offenses, Barton said, advanced high school quarterbacks are at a premium.

“Fifteen years ago, college coaches could look at a guy and say ‘He’s raw, but he has mechanics, and he has upside,’ and they can spend some time developing him,” said Barton, who founded Alliance QB Academy, a quarterback training program in the Northwest. “Nowadays, systems are so complex, they don’t have time to work on a guy. They need a guy that’s really polished. … The whole industry has changed.”

Naturally, quarterback trainers tend to be in the regions where there is the highest concentration of elite quarterback recruits.

In California, trainer George Whitfield has privately coached several NFL quarterbacks, such as the Titans’ Marcus Mariota.

In Georgia, which has produced 16 top-10 quarterbacks in the past 10 years, Atlanta-based trainer Quincy Avery has coached players like the Texans’ Deshaun Watson.

When Barton was starting his academy, there was some resistance by local parents.

“Some people didn’t understand,” he said. “I mean, there’s AAU basketball. Select baseball. They just know. But when (private quarterback training) started, people were like ‘What?’ We’re still in those stages. Now, more trainers are established. It’s more known and commonplace.”

There is an economic barrier, Barton acknowledges.

Private training can cost up to thousands of dollars. Some communities might not be willing to pay for the privilege, and some regions might just not have a market for it.

THIBODAUX — As he prepared this week to host the 23rd annual Manning Passing Academy alongside sons Cooper, Peyton and Eli, Archie Manning cou…

Backyard passing game

Although the annual Manning Passing Academy is in Thibodaux, there isn’t a major presence for private quarterback training in Louisiana.

There are a few minor presences, such as National Football Academies, which hosted a camp at St. Thomas More Catholic in 2006. Since then, Shane Savoie, the offensive coordinator at St. Thomas More, has studied passing techniques and now trains quarterbacks in Louisiana for NFA.

“I really fell in love with how they taught quarterback play, how they broke it down to biomechanics rather than just, 'This is what so-and-so does, and this is how so-and-so does it on Sundays,' ” said Savoie, who also works with the Manning Academy and said he has trained nearly 80 quarterbacks in the past decade. “Their whole approach was answering the ‘Why?’ with biomechanics, and the scientific rationale behind all that really intrigued me. It moved me from ‘Do I just think I’m making the kid better?’ to ‘Am I actually teaching him something that will make him cognitively and physically better because it’s based in science?' ”

The coming years will show whether 7-on-7 and private quarterback training will take root in Louisiana.

The number of elite quarterbacks is already ascending: Ponchatoula's T.J. Finley is ranked the No. 8 pro-style quarterback in the class of 2020 and is committed to LSU.

"I think you're going to see us grow," Savoie said.