I have this irrational fear of passing out in the shower. It's not the risk of splitting my head open that scares me, or that no one would find me. It's the idea that someone could. Most likely, my boyfriend Ben would be the one to discover my hairless body, trying not to panic as he frantically dialed 911. Unconscious me would be wheeled into a florescent-bright E.R., my bald head on display, and I'd be exposed. I wouldn't have my wigs or scarves or hats to cover myself up, and I wouldn't have that power back for days.

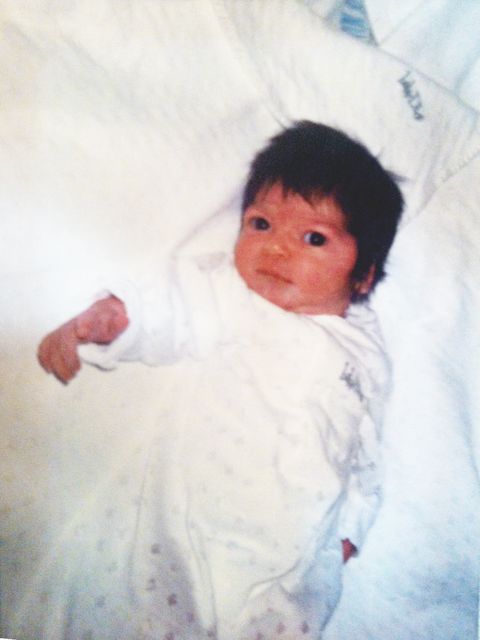

Before I lost my hair, I looked like this:

And I had a nice little cookie-cutter life. My then-boyfriend and I lived in a sunny San Francisco apartment, which I moved into from New York after dating long-distance for about 18 months. He worked in finance and I was an editor at a digital start-up that focuses on dispensing career advice to millennial women. On Saturday nights he made pizza from scratch and on weeknights I made things like a roast chicken or bolognese. Sometimes we went out. Sometimes we slow-danced in the kitchen, a vinyl record playing on an old turntable in the other room, while the pasta was cooking.

By the time we broke up, I looked like this:

My thick head of hair took about 90 days to go. It started in the shower, the water pressure dislodging long swaths. Knots formed in my comb, the touch of the plastic prongs enough to pull the strands away from my scalp. I woke up to hair on my pillow and swept it up from our hardwood floors.

I batted a once-a-day crying average. My tears peaked the day my ex, lying next to me, told me he was no longer sure if he saw a future with me. I asked for time. I stood on the side of the road outside of our fancy Sonoma retreat, the cars surging past me and the vineyards across the street, and called my mom. I called my mom a lot during those first few months of losing my hair.

Before my mom and dad knew my gender, they knew I had a mop on my head. "Look at all that hair!" the doctor said within seconds of delivering me, then announced that I was a girl.

It wasn't just my head. I was covered in hair. As soon as I was old enough to realize it, I spent an exorbitant amount of time trying to get rid of it. One day in elementary school, some of the other third graders made fun of my hairy legs, so I came home and asked my mom to shave them. At 8 years old, I stood in the bathtub wearing a bright green bathing suit with pink and white flowers as my mom gave me a final warning. "You know, once I do this, you're going to have to keep doing this forever." I nodded, do it, and she put her dollar-store razor to my skin, gently going from ankle to knee, knee to hip. And that's how I did it up until 16 months ago.

In July of 2015, my dermatologist, Dr. Lavanya Krishnan, told me my hair was rapidly falling out because I had alopecia areata. She offered me a tissue box and explained in a delicate tone that it's an auto-immune disease that can be triggered by anything — stress, even a bad cold that "flipped a switch" in my immune system. Essentially, my body started treating the cells that make the pigment in my hair follicles as enemies and went into attack mode. Alopecia areata affects 6.6 million people in the U.S. And for most, the hair loss is limited to small, round bald patches. Another, rarer form is totalis, which claims all the hair on your scalp. The rarest is universalis — the loss of everything, down to the stuff you get during puberty. (Hey, no more waxing!) During that first appointment, Dr. Krishnan warned me that I may lose my eyebrows and eyelashes too. I refused to believe that would happen, but I think she knew I had a long journey ahead of me.

Whenever I explain alopecia areata to someone in real life, they usually ask me how I got it, and I say I have no idea — that while it can happen randomly to kids and teens, for adults it's often caused by stress and sometimes takes place about two to three months after a traumatic or substantial life event. But the idea that I have no clue why or when my alopecia started is a lie.

Before I had an irrational fear of fainting in the shower, I had an irrational fear of HIV. One frigid January evening at dinner with friends in New York, I used a toilet that I realized was dirty only after turning around to flush it. Afterward, I convinced myself that the diluted spot of blood I'd seen was infected, and that it somehow infected me. I knew better, and I sure wasn't proud of it, but nothing could stop my "what ifs." When I still felt frozen in fear a few weeks later, I went to an urgent care facility in Manhattan and got a rapid response HIV test. The doctor printed and signed a physical piece of paper as a constant reminder, whenever I needed it, that I was negative. Soon that certificate of health started to feel more like a Band-Aid. I convinced myself that there was still room for error and called the urgent care office to speak with the doctor again, but he declined, so I got tested again. And then a third time when I had my annual OBGYN check-up at the end of the year. Those results finally convinced me, but I just invented another health scare and then another, leading up to July 1, 2015, when those first clumps of hair filled my sink.

By day, I was a polished young professional, known for my bubbly personality at the fitness magazine where I worked before moving to San Francisco, and I maintained that veneer whether I was at drinks with colleagues or working out with friends. By night, I'd spend hours Googling my irrational fears — pouring over message boards, Q&A pages, WebMD — because I needed to prepare. Throughout my mid-twenties, I convinced myself that I had everything from stomach ulcers to throat cancer. I figured the worst was bound to happen, and I would rather be prepared than caught off-guard.

It was hard for me to fathom how other people existed without anxiety, because it always felt so ingrained in me. Through therapy, I eventually realized that I didn't have to live that way. While there's a stigma around medication for mental health, I have no shame in sharing that a 60 milligram daily dose of Cymbalta has lifted a weight off my shoulders. But before I found that relief in February of 2016, I still had to make it through those first daunting summer months of developing alopecia universalis, a month-long "break" with my boyfriend just before the holidays and finally a painful breakup shortly after the New Year.

When my hair first started to go, my ex would say over and over, "I just want you to be okay." I had moved away from my family, friends and everything else I knew to live with him in San Francisco. I convinced myself that I needed to skip the emotional aspect of my hair loss and be okay — for him, and so that I didn't become a complete failure at this major life step.

But while I tried hard to ignore it, losing my hair is what finally cracked my happy, bubbly facade. I was never just the "Devin" everyone knew as the perky editor and Suzy Homemaker Chef. It was all an act to cover the sharp edges that poked — at worries, at fears. But as the season turned from summer to fall, even as I was losing my eyebrows and lashes, I still thought I could keep up an outward appearance of "okay." Before Christmas, for example, I hosted a cookie decorating party at my place.

That night morphed into what I imagine must happen to women who are trying to get pregnant but can't — you suddenly see pregnant women everywhere and are constantly orbiting around people having conversations about babies, even when you're just standing in line for your morning coffee. Never before had I noticed how often people talk about hair. After we spread red and green icing over our cookies, we all went out to dinner with our significant others. A few drinks in, my friend, someone who knew about my alopecia diagnosis and whom I normally admire for her candid opinions, went on a diatribe against a celebrity who'd recently shaved her head. "A woman needs to be feminine — and you need some hair to be feminine," was the last thing I heard before I excused myself to the restroom and cried.

The more I tried opening up to people about my hair loss, the more I realized that people who aren't in your shoes rarely know what the heck to say to you when you're going through a crisis. "At least you don't have cancer" is a well-meaning comment that I hear often, which makes me feel ashamed. "I know, and I'm so grateful for that," is what I usually say back, but inside I've shut down in the way that we often do when we're reminded that we could have it so much worse.

It IS a big deal.

When I hear that from a friend, it's like knocking open a fire hydrant. I'm able to go back to those first few days of running my hands through my hair, feeling it fall between my fingers, and all of that raw shock and fear is still there, and I'm able to let it out. I ugly-cry — big fat, snotty tears — and it feels so freaking good.

This was the last time I went out in public with my real hair: July 19, 2015, at the Georgia wedding of one of my sorority sisters and close friends today. Other sorority sisters — ones I hadn't seen in years until that weekend — started knocking on the bathroom door as I was getting ready so that they could get ready too, and I frantically scooped up thick webs of hair off the beige-tiled floor so they wouldn't see. Then I tied a colorful scarf around my head and walked out the door.

I spent a lot of money on scarves at first, but after this wedding, I knew I was not living with the small-round-patches kind of alopecia areata and started looking for wigs. I had a hard time even saying the word out loud. Wig. It felt foreign on my tongue. Alone one late-July afternoon, I went to a shop near the Zuckerberg San Francisco Hospital, where a gentle older man let me try on various lengths and colors.

"Does your kitchen faucet have a nozzle?" he asked me.

I felt overwhelmed and said I didn't know, but he was asking because he wanted to teach me how to wash the wig.

"You want to let the shampoo set in the hair for a few minutes, then rinse it — but don't soak it — so that the water goes down in one direction, like this."

I left the shop $1,500 poorer, got the wig cut and dyed, and then spent a cab ride home taking selfies, trying to pick one to send to my mom. I'm not good at selfies and only got into a groove once I was back at home, on my couch. Finally, I chose the one on the left. A few minutes later, I took the one on the right, and kept it to myself.

A few weeks later, in August, I got bangs cut into my wig to hide my increasingly sparse eyebrows. I was seeing a therapist by this point to help me navigate my rapid hair loss and crumbling relationship, and at the beginning of one session she mentioned an NPR segment about a magazine story, featuring women with hair loss due to chemotherapy and for other reasons. When I googled it on my own later that day, I discovered Carly Severn, a British woman who lived in the Bay Area and had lost her hair to alopecia areata at age 19. She changed everything for me. Through YouTube tutorials, she taught me how to draw natural-looking eyebrows and thick, winged eyeliner that would help conceal a strip of false eyelashes. That became my look, and once I figured that out, life became a little easier.

Like Carly, I started wearing beanies at the gym or on hikes with friends. And I bought a second wig, cut into a short bob, that I wore to the beach or while running errands around town. Eventually, it would become the wig my boyfriend Ben likes the most, and what helped me to feel sexy again. (PS: In a you-can't-make-this-up turn of events, when Ben and I met, it wasn't until well into our first date that I found out he developed alopecia universalis too, when he was a teenager.)

Currently, there is no cure for alopecia areata, though there are promising clinical trials out there. (I've tried one, but the medication didn't work for me.) While there is a slim chance that my hair could grow back randomly, I have to assume that my hair loss is permanent.

I grew up loving hair, and all the things that came with it. One sensory aspect I miss the most is reading in bed with my hair still wet from the shower, soaking my pillow and dripping onto my t-shirt, and smelling the strawberry scent of Clairol Herbal Essences shampoo. I realized recently that just because I lost mine doesn't mean I have to stop caring about it. Now, Hair Wash Days bring me joy. Every two weeks, I can smell faint whiffs of shampoo on my damp wig. My wig dries overnight and in the morning before work, I carefully run my straightener over small batches, watching with pure delight as they fall into bouncy curls.

If you asked me if I wanted my hair back again, I'd say "yes" without a blink or a breath. But I wouldn't take back how I felt about it, or even the swift and painful breakup that took place one year ago today as a result. After months of trying, I eventually had to accept the fact that my relationship wasn't strong enough to overcome my diagnosis, because in a way, it had made me into a new person. Rather, a deeper, more honest version of myself: Someone who isn't afraid to show emotion even if it's messy sometimes, and who is more compassionate with others.

I had a relatively easy life before I lost my hair, and I understand now that back then, I couldn't fully empathize with people in pain. When I tried out for the dance team in high school, I got in. When I picked my first-choice sorority in college, they picked me too. When I applied to my dream job at Glamour magazine after graduation, they hired me. And I just didn't feel that deeply when other people in my life confronted loss. I sympathized with them, and tried to console them, but it was like trying to speak another language. I couldn't really recognize their pain, and now I can. My relationships are stronger and deeper today because of that important lesson. Now, I don't just try to make everything okay right away. I listen. I ask questions. I say go ahead and cry; big fat, snotty tears are good.

My therapists have always helped me confront my fears by asking me what I would do if they became a reality, Let's say you tested positive for HIV. What would happen next? What would you be afraid of? When you do that, you're able to work through your fears and see that maybe you don't need to be so scared after all. Eventually things just become your reality. You'll know nothing other than to be strong, and your voice will be there waiting for you when you decide it's time to use it.

Note: In the summer of 2017, Devin started a clinical trial that resulted in full regrowth with no known side effects and is now taking a similar medication, all under the guidance of her current dermatologist Dr. Brett King. If you have been diagnosed with alopecia, you are encouraged to email Devin at devin.tomb@gmail.com for more information.

Devin is the head of content at The Muse and was previously executive editor of Prevention.com. Her work has appeared in Cosmopolitan, The Cut, and SELF.