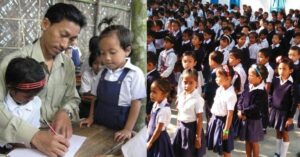

Meet The Former ULFA Militant Bringing 1000s of Jobs, Fixing Schools & Hospitals

“My parents always told me to be kind and help others if you’re capable. Their only expectation of me was that I become a good human being.”

How does one go from an idealistic youth to a militant, to a prisoner and finally a reformer and social worker whose efforts have uplifted tens of thousands of lives? But this is exactly the wonderful and poignant journey of Moni Manik Gogoi, an extraordinary man with an extraordinary life.

Gogoi (53), a resident Shalmari Dighalia village of Upper Assam’s Tingkhang town in Dibrugarh district, had only one objective throughout his life—development for his poverty-stricken people.

This elegant and classy standing lamp is handmade by the craftsmen of Assam using traditional bamboo nets, and will envelop your room in a beautiful warm glow!

Growing up through the seventies and early eighties, what Gogoi saw was rampant poverty. There were occasions when his mother had to beg on the streets so that her family could survive when his father fell ill.

Despite living in an oil-rich region, his village saw no development. There was no infrastructure and no employment prospects for the region’s restless youth. As a consequence, the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), a banned militant outfit that sought to violently overthrow the Indian government with a radical message of economic self-reliance, captured the imagination of many youngsters like Gogoi.

For nearly a decade, Gogoi actively worked for ULFA. But he never took up arms, already proving how special his world-view was.

ULFA & Prison

“In 1987, I first came across the ULFA guhaaris or appeals distributed around my village. Their message for an independent Assam free of poverty and full of opportunities attracted me deeply,” says Moni Manik Gogoi, in a conversation with The Better India.

He was an effective organiser because of his ability to maintain good relations with members of different ethnic, tribal and religious communities.

“When we first met Moni Manik during our active ULFA days, we found that this man had a tremendous influence on the people of areas of operation. People shower great affection on him and the man is so gentle, decent and his thoughts are so noble,” says Mrinal Hazarika, a former commander of an armed ULFA battalion, in a 2017 documentary titled ‘Bejewelled Rebellion’.

However, joining an insurgent group like ULFA meant working underground. In hiding, he worked in districts like Jorhat, Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Sibsagar and others.

“When I joined ULFA, the police were always looking for me. I knew that if I stayed at home, they would catch me. So I was on the run living from one village to another. In 1991, I had gotten married but would stay in a neighbouring village and visit home when possible. By 1994 living in Assam became increasingly difficult with the constant threat of army and police raids. In 1994, along with 150 people, I went to the jungles of Myanmar to ULFA’s training camp in the forests of Myanmar and lived there for a year,” he recalls.

This was just three days before his second son was born.

“But during the training camp, I was reluctant to take up weapons training – even if my life was under threat. I’m a farmer at heart, live close to nature and working towards social welfare is my only desire. I had no desire to kill, and thus became the only one in the camp without weapon’s training. In hindsight, I couldn’t believe they agreed to my condition for no weapons training.” recalls Gogoi.

Before and after joining the camp, he started a whole host of initiatives for his hometown. In 1993, he unofficially started the Tingkhang Kala Kendra — a space for kids to learn how to sing, dance, act and draw. (It was officially opened in 2003 after his association with ULFA ended).

A lot of children learnt drama, theatre, dance, singing, weaving and farming there. Back when he started it, there were 100+ kids. In 1995, after his return from Myanmar, Gogoi also started a music school in his village and a cultural stage as well for locals to perform songs, learn theatre and other cultural activities.

Through 1995, 1996 and 1997, he even helped build hospitals, agricultural farms and organized self-help groups. But living underground came with its costs.

The police and military were still looking for him. His father and a brother who was five years younger than him would regularly face physical and mental abuse by the authorities for not disclosing his current location. In fact, Gogoi’s father died from his injuries after one particularly brutal crackdown.

“All that came to an end in July 1998. Coming down from Jorhat district, I was going to my village for an event. Police entered my home at 3 am and captured me when I was asleep,” remembers Gogoi.

The police took him to Tingkhang Thana and later booked him under TADA. He spent six months in Dibrugarh District Jail, while still earning the love and respect of the people in his village.

Prison was rough. He recalls 1000+ people cramping together, occupying the district jail with bad food, no clean water and clothes, besides the absence of piped water in their toilets. During his stay in prison, he organized the inmates in peaceful protests and even wrote letters to jail authorities and the deputy commissioner, describing the terrible conditions.

“Thanks to my letters, the quality of rice served improved, 200 additional blankets were brought and piped water extended to our bathrooms. Even the jail was renovated from the inside,” he recalls.

For The People

Reflecting on his time with ULFA in prison, he grew increasingly disillusioned with the movement, particularly the extreme violence, and frustrated at the lack of any tangible benefits it had accrued for his people.

“I also understood that an armed struggle against India would bring no real benefits for my people,” he says.

After he was released in 1999, his first port of call wasn’t ULFA, but his village. The people accepted him with open arms.

Soon after his release, he found his first cause. The Lower Primary School that he had attended as a child was going to have its centenary celebrations in January 2000. But the school was in a terrible state.

The committee for the celebrations enlisted him as General Secretary, and he helped them renovate the entire school thanks to funds from Oil India Limited (OIL), a public sector enterprise, under their corporate social responsibility (CSR) arm.

Besides renovating the school, the following years saw OIL assisting him in running skill development programmes for the youth in hospitality, nursing, tailoring, electrician work, etc, in his town.

Thanks to their assistance, he also helped organise 2000 women-led self-help groups in Tinsukia, Sibsagar and Dibrugarh, besides facilitating the construction of community centres, building toilets, poultry farms and opening weaving centres as well. He also oversaw the functioning of a local mobile dispensary.

“Moni Manik Gogoi is a very interesting example of changing times, changing mindsets and changing perceptions in Assam. He got associated with Oil India Ltd with officers like Prasanta Borkakoti and worked on this project called Project Rupantar. [Since 2003] Rupantar has brought about such interesting changes where the farmers are tilling their land with mechanised implements, young people are working computers, the women are weaving in improvised looms, and this has brought about a tremendous economic change in the countryside in and around Naharkatia and Duliajan,” says veteran journalist and author Samudra Gupta Kashyap, in a 2017 documentary called ‘Bejewelled Rebellion’.

Gogoi even went on to facilitate the renovation of hospitals.

“Back in 2001, my brother got mumps, and I had taken him to the Naharani government-run primary health centre–the only hospital that catered to two constituencies of Tingkhang and Naharkatiya. The conditions were horrible. Even the villagers sought me out to fix the Naharani government-run health centre. It had no proper beds, rooms or water supply, and regular electricity supply. The villagers asked me to do something about it,” says Gogoi, who later helped raise Rs 25 lakhs to rebuild parts of it. Of the Rs 25 lakhs, OIL donated Rs 12 lakhs while residents of Tingkhang and Naharkatiya donated Rs 13 lakh.

Even the villagers had contributed their share with beds and helping build rest halls. Looking at the progress his efforts had created, the administration helped set up an operation theatre complex in the hospital. The entire renovation process took about four years. In 2005, he did the same for the hospital at Tingkhang 6 km away from home, which took about 1.5 years.

However, his biggest project is the ongoing Sasoni-Merbil project–Assam’s first big-budget eco-tourism initiative revolving around Merbil lake in an area called Sasoni in the Naharkatiya Tehsil of Dibrugarh district.

Back in early 2010, locals wanted Gogoi to help them build a hospital there, but need the land allotted for it, he saw a Beel (lake-like wetland with static water), which he thought was ideal for an eco-tourism project.

“There, I saw so many migratory birds, fish, flora and fauna, and couldn’t help but notice the potential for this area (measuring around 1550 bighas) to become an eco-tourism destination,” he recalls.

Home to many species of migratory birds, animals like the endangered Indian softshell turtle, medicinal trees, the scope for activities like trekking, boating, building eateries, parks and cottages for boarding, was massive.

Locals initially weren’t too happy with the idea because they just wanted the hospital. He shared his idea with the local Dibrugarh district forest officer and deputy commissioner.

“Gogoi actually explained to me about the potential of this place and showed me around. So I talked to the Deputy Commissioner after coming back. He took an interest in that and then both of us started working on this and finally we thought that its a place which has a lot of potential to develop,” says Anurag Singh, who served as DSF from 2007 to 2011.

Soon, the district administration offered funds for the project under the National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme and other such rural development schemes. OIL too had joined the project as a partner. Eventually, Assam Tourism Development Corporation sanctioned an amount of Rs 3 crore for the project.

Alongside the deputy commissioner, he convinced locals of its potential. On September 26, 2010, they finally inaugurated the project with more than 20,000 people in attendance.

Thus far, Gogoi claims this remarkable project has managed to employ about 50,000+ people in the area working in catering, boating, construction, guest house cottages, and restaurants.

Supporting him through all his endeavours is his wife Dipali. Both Monik and her are high school sweethearts. “She understands me well and has always supported me. Even when I had left home, she never asked me to surrender. My wife believed in the social work I did. Her only request to me was that I stay alive,” he says.

He has no plans of stopping anytime soon and sees immense potential for the region to become a tourism hub in India, which he believes will bring in more money for its people.

“I belong to a poor family. My parents always told me to be kind and help others if you’re capable. Their only expectation of me was that I become a good human being. If I do good work, they said I would never be alone. That has actually come true,” says Gogoi.

Also Read: The Tiffin Box is Transforming a Remote Assam District, Thanks to this IAS Officer

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.