Sweeping new internet censorship rules have gone into effect in China, prompting concerns that authorities will further control information and online debate as the country reels from the coronavirus outbreak.

China’s cybersecurity administration has since Saturday implemented a set of new regulations on the governance of the “online information content ecosystem” that encourage “positive” content while barring material deemed “negative” or illegal.

The regulations, released last year, come as Chinese internet users have become increasingly critical of censorship because of the removal of news and comments about the government’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak. Volunteers have been preserving removed content while internet users have been trying new ways to evade censors.

On Monday, the hashtag, “Online news eco-system governance” had been viewed more than 3 million times on Weibo. But some news accounts posting articles on the topic had disabled the comment sections. On other posts, users wrote: “In the future there will be only good news, and no bad news.”

“They only want us to see what they want us to see, and hear what they want us to hear,” another wrote. “This is basically the internet version of social policing,” another said.

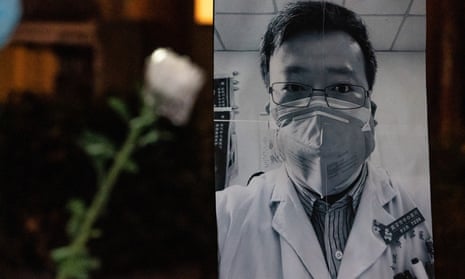

“What about Li Wenliang?” one use wrote, referring to the late whistleblower doctor in Wuhan who attempted to speak out about the virus early on in the crisis. Li’s death prompted calls for China to protect the fight of freedom of speech, as outlined in the country’s constitution.

Censorship in the form on restrictions on content have been steadily increasing over the last few years, with platforms taking down LGBT and feminist content deemed as “in violation” of regulations. Fan fiction website the Archive of Our Own, featuring some LGBT content, appears to have been blocked since 29 February.

The rules, which consolidate previous provisions, go further and encouraged content producers to promote ideological content like the socialist theory of Xi Jinping in a “comprehensive, accurate and vivid way.” Content should promote unity and stability as well as underline China’s economic achievements.

Stil, the rules are vague in their definitions of what constitutes “negative content,” which under the rules include “sensationalising headlines”, “excessive celebrity gossip” as well as “sexual innuendo” and broadly any content that can have a “negative impact”.

“It is harder to imagine how [these standards] will play out in the more interactive online setting where every citizen can become a content creator,” wrote Jeremy Daum, senior fellow at the Yale law school’s Paul Tsai China centre who has translated the regulations.

“Imagine trying to understand whether a blog or forum post’s title is too sensational, or trying to track down all ‘sexual innuendo’ online in twitter posts and comments sections.”

One commentator on Weibo said: “Such meaningless rules. In addition to providing the government more excuses, it’s not even clear how this should work.”

Additional reporting by Lillian Yang