One of the great joys of preparing soil where vegetables will flourish is pissing on it together as a family to add a healthy, free-flowing, and free-of-cost nitrogen dose, which otherwise would be flushed down the toilet. My seven-year-old daughter, Josie, and I have been urinating away in the bright air of spring’s lengthening days in the Catskill Mountains, where I live, and where Josie, who spends most of the year with her mother in New York City, 140 miles to the south, often comes to visit. We sing songs as we piss. “Springtime for Hitler” is a favorite, followed by “We Will Rock You.”

Last year, with Josie and my girlfriend, Viva, who was born and raised in the Catskills, we built and tended the first productive vegetable garden of our lives. I was 45 years old, a latecomer to the soil. The garden eventually fed us with such bounty that we were freed, if only fleetingly, from the agricultural-industrial complex.

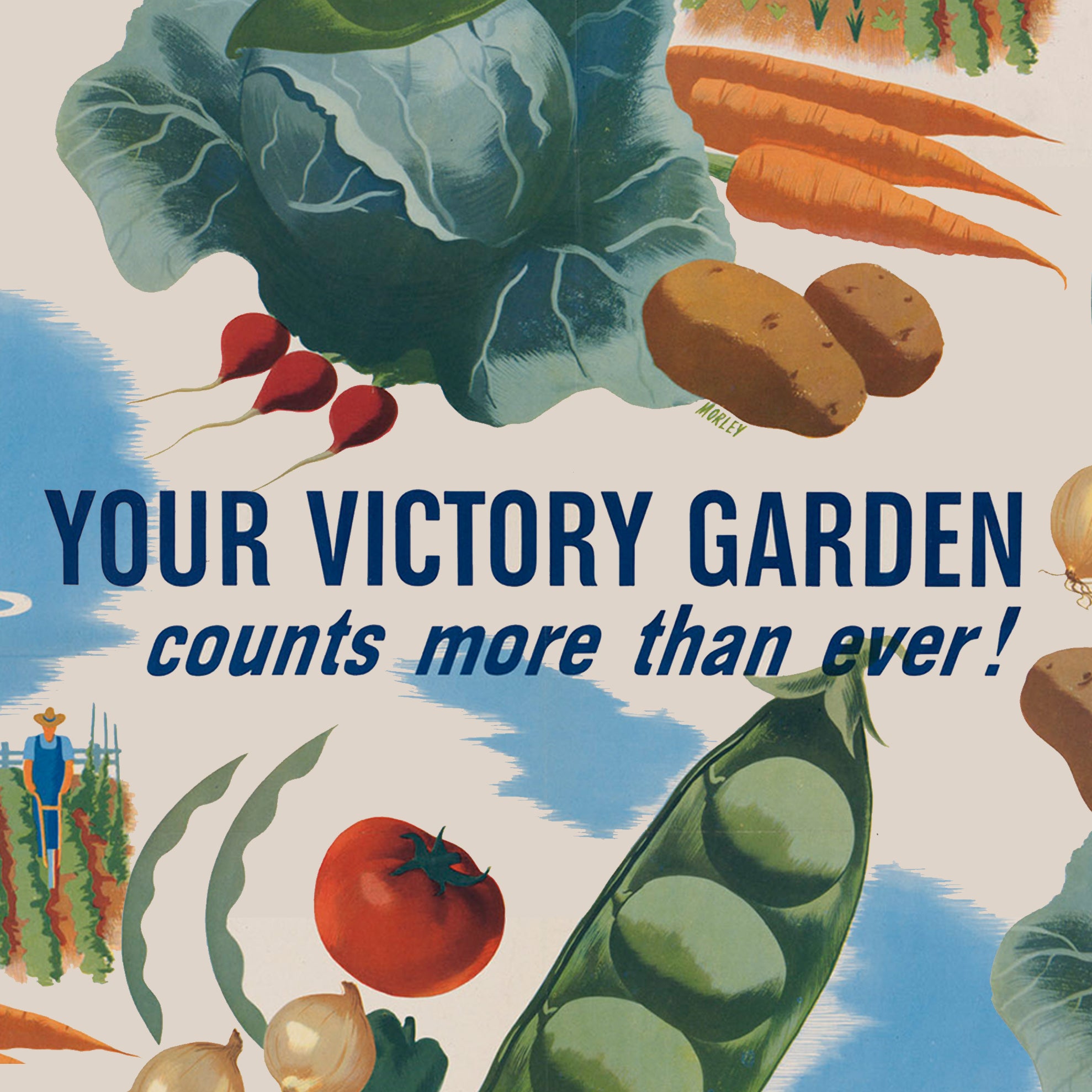

A year later, in the spring of 2020, a sizable number of my fellow Americans, prodded by the COVID-19 pandemic, appear to have joined in the tilling of soil. Used to constant, unquestioned plenty, and shocked at seeing empty supermarket shelves, the good citizens got the message that a backup plan, a kind of prepper-lite initiative, might be in order. Fearful of going hungry, they have apparently started trying to grow their own vegetables at rates not seen since the collective Victory Garden movements of the First and Second World Wars. The rise of the modern coronavirus garden may be one of the unintended positive consequences of the pandemic.

It’s strange now to think that when Viva broached the idea of a food garden in the spring of 2019, I didn’t want any part of it. I was putting the finishing touches on a new book, and I told her a garden would be a pain in the ass, a lot of work—and it was.

We had no idea what we were doing, and the first season was a process of muddling through. Our nine acres sit at 2,400 feet, on a ridge in agricultural zone 5A, which means an average last-frost date of mid-May, but it can be later than that. It’s a place of long winters, windstorms, lake-effect snow from the west, and early-autumn cold—the classic elements of a short growing season. The soil is rocky and thin, and our house is surrounded by forests of maple, beech, birch, and hemlock that shade out the light. We would either have to chop them down in numbers unacceptable to me or make do with what patches of sun we could find.

Last spring, a month before the final frosts of May, we sowed kale, cucumbers, zucchini, peppers, pole beans, and tomatoes in little starter pots that festooned the rooms of the house. It was done in haphazard fashion and in a race against time, because we were late with the planting. The sprouts huddled pitifully against windows facing east, their tiny tender leaves leaning together, bent as if in prayer toward what little sun they could get. We watered and fertilized and watched and waited.

In a humble 20-by-20-foot plot beside the house, we prepared the soil, which was full of weeds and rocks. The old saying about the Catskills goes that God made the earth in seven days and on the eighth day smashed boulders and threw the fragments at our mountains. So we picked and hauled rock and dug out tough, sinewy roots, working under gnat attack on the few warm, clear days we got but more often laboring in cold fog or drizzling rain. We tilled and turned the soil, added outrageously expensive compost bought at the feed store in town, and urinated, and then tilled and turned some more. We ground eggshells into fragments and sprinkled them in the dirt bed to add calcium, and we threw in our coffee grinds, though not too much, because that would acidify the soil.

We started to think about the future, the next season. If compost was so expensive, why not produce it ourselves? We began the process in a pile near the house, using organic nitrogen-rich matter like vegetable scraps, tea leaves, more coffee grinds, and even the gum Josie chewed. Mixed with the nitrogen, we added the organic carbon of cardboard, newsprint, paper towels, beard trimmings, lint from our dryer, leaves, twigs, and cut grasses. When I described our nascent pile to a friend who had years of experience in composting, she said it was “redneck,” which I figured was OK. It would take six months to produce soil from our jettisoned crap, but better to have soil than put it in a landfill.

For a city boy like me, born and raised in Brooklyn, where I had spent most of my adult life, this was all very new. Once you get your hands in soil—really get dirty with it, feel it under your fingernails—there’s a change in perspective, and you’re someone different. You’ve opened the tiniest of windows onto the ecological reality of the forces that sustain human existence, the biogeophysical relationships of water, sunlight, air, earth. Quite suddenly, what seemed mysterious quotients—say, the balance of phosphorus, nitrogen, carbon, and potassium—become commonalities of understanding and, eventually, of wisdom. The plants that depend on all those factors in harmony rise up, or they don’t.

It’s hard to express the pride and lovingness and delight in seeing a plant germinate, and grow tall and hardy, and then flower and put fruit out. When the crop came fresh and healthy last summer—there wasn’t a hint of blight, and no insects attacked it—I felt a bit like Viva and I had brought green babies into adulthood. We will never not do it again.

Go to any number of online seed purveyors nowadays, like Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, Savers Exchange, and Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, and you’ll find them stripped of supplies, often cutting off orders. Home Depot’s website says that virtually all the seeds it sells online are out of stock.

This kind of panic buying has been happening across the country. Forbes recently reported on a “rush of people buying gardening supplies” in California’s Sonoma County. Oregon State University’s Master Gardener program offered an online vegetable course, made free through the end of April, and the Facebook posting about it was shared 26,000 times. The executive chairman of Burpee, the nation’s largest seed retailer, told NPR that he had never seen a spike in seed purchases this large and widespread.

Do these things signal a turn toward something lasting and meaningful, a new era of localized food production led by a new generation of gardeners? Or is the seed rush a mindless herd dynamic driven by fear? Will people put in the time and labor to garden once the pandemic is over?

At the height of the Victory Garden movement during World War II, Americans took to tilling soil in such large numbers—cultivating food in pots on fire escapes and rooftops, in backyard plots, in empty city lots, and in rural and urban spaces alike—that as many as 20 million new gardens produced an estimated 40 percent of the nation’s fresh vegetables.

With collective determination, we could probably replicate (and perhaps eclipse) that productivity today and do it on a human scale in a manner that’s decentralized, locally controlled, and outside the ag monopoly, thereby making ourselves, as individual citizens, hyper-resilient to systemic supply shocks. In an ideal world, this type of social and economic resilience is exactly what the pandemic will teach us we need.

This spring, with Josie out of the closed New York City school system, she and Viva and I again planted seeds together. “Daddy, Daddy, wake up! Alert!” she shouted one dawn in March, and Viva and I woke up startled, thinking something was wrong.

No, it was just that the peppers had sprouted.

We had been talking the night before about the difficulty of growing peppers, how they needed just the right measure of heat and light, how in the stingy sun and enduring cold of zone 5A they might not do well.

But now they’d come up, and Josie was mad with joy, exactly as a child should be at the sight of food emerging from soil she’s seeded. As it happens, Josie would never have gotten to see those first germinations of spring if it weren’t for the fact that she was homeschooling with me, holed up in the mountains far from the viral epicenter—she would have been in New York, in a room with four walls, at her school. In a silver lining to the pandemic, horticulture, hands-on, was now a daily part of her curriculum.