Joshua Harris was just 22 in 1997 when he published I Kissed Dating Goodbye, a dating guidebook for young Christians that advised them to do anything but. Dating was a “training ground for divorce”, he argued in the book, which sold almost 1m copies worldwide. It also made Harris a superstar in the Christian purity movement, a pro-abstinence crusade that began in evangelical churches in the 1990s and became well-known in the purity ring-wearing hands of Jessica Simpson and the Jonas Brothers. Many authors came after Harris – John and Stasi Eldredge, Hayley DiMarco, Tim and Beverly LaHaye – all of them in the US, where religious publishing is worth $1.22bn (£1bn) a year.

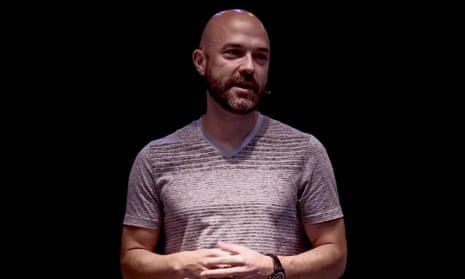

Now 44, Harris made headlines this week when he revealed he no longer considers himself a Christian. He has been issuing apologies for his own books over the last decade, even making a documentary called I Survived Kissing Dating Goodbye. On his Instagram this week, he wrote: “I have lived in repentance for the past several years – repenting of my self-righteousness, my fear-based approach to life, the teaching of my books, my views of women in the church, and my approach to parenting to name a few.”

Dianna E Anderson, who left the purity movement in her 20s and is the author of Damaged Goods: New Perspectives on Christian Purity, says its relationship guides have inflicted lasting damage on young people desperate to preserve their holiness while battling hormones.

“As a woman, I was taught that women don’t feel or experience desire, so I suppressed any and all thoughts along that way, to the point where I was practically asexual all the way up until I was 23, and I didn’t date until I was 25,” she says. “Turns out it’s really hard to date when you’re a super-repressed purity-obsessed evangelical.”

Most Christian purity guidebooks dish out similar advice. The golden rule: no sex before marriage, ever. The relationships are always heterosexual and monogamous, while the sex is always deeply conventional – a mindset that has left a generation of Christian teens muddled on the “purity” of acts like oral sex, and inspired the Garfunkel and Oates tune The Loophole.

Male desire is treated as animalistic and uncontrollable, with many writers – including Harris – advising that men should avoid the company of women who aren’t their wives. (This was once called “the Billy Graham rule”, after the evangelical preacher who advocated it, but is increasingly rechristened “the Mike Pence rule”.) In his 2005 book Sex Is Not the Problem (Lust is), Harris supported a strict interpretation of Matthew 5:28, where even glancing at someone attractive on the bus was a sin. Anderson calls it the “There’s No Such Thing As a Random Boner principle”, where “lust becomes a thoughtcrime … every single hormonal moment becomes a life-death struggle for your soul and something to repent of. That’s such a huge weight!”

Anderson still lives with the after-effects of being raised on such ideas. As a teenager, she believed that women didn’t feel arousal and men were uncontrollable, which “caused me to imagine that losing my virginity would essentially be rape. That if I wasn’t married, then the only other way I would lose my purity would be if I wasn’t strong enough and a date raped me. Of course, I didn’t see it as rape – I saw it as a man being animalistic and just giving in to his sin. I had no mechanism for understanding that I could possibly consent, and that it would be something I would want to do. In my teenage, evangelical imagination, I hoped and prayed to be put in a scary sexual assault situation so that I could prove how faithful I was to God.”

Harris is now leaving his wife after 21 years of marriage. Anderson says disillusionment is not uncommon in a movement built on the fallacy that if you marry young and abstain, you’ll be happy. But she does not think others will follow Harris’s lead, as criticism tends to make them double down on their beliefs. “You see this throughout the Southern Baptist Convention, and through the abuse scandals at Harris’s former denomination, Sovereign Grace Ministries. They refuse to acknowledge that a sexual ethic based simply on telling women they have to say no until they’re married, at which point they cannot say no any more, is flawed.”

For many like Anderson, Harris’s apology is too late, having spawned a whole subgenre of books by authors who won’t also recognise the damage they have done.

“I don’t think evangelicals should be contributing to the conversation about purity and sex anymore. It’s time for them to listen,” she says. “As a queer woman, I was so repressed that I didn’t discover my own queer identity until I was in my late 20s, and I feel like important parts of myself were stolen from me because of this theology. At this point, it’s their job to listen. Unfortunately, they don’t seem ready to.”