The official commemoration of the first world war focused mainly on men. The national leaders and the multitude of troops who fought were men. Some attention has been drawn to the women whose husbands were in the forces with many being widowed and to the nurses who cared for wounded and dying soldiers. A minority worked close to the frontline in France and Belgium, often putting their own lives in danger. Many more looked after casualties once they were brought back to Britain. Birmingham University became a huge military hospital, where hundreds of nurses treated 64,000 patients.

It is usually overlooked that working class women played an important role ensuring that the soldiers had adequate ammunition. It was clear from the outset that British troops did not have enough shells, bombs and bullets. Private owners expanded their output in 1914, and following the appointment of David Lloyd George as munitions minister in 2015 the process accelerated with two major pieces of legislation, including the Munitions of War Act.

The government was empowered both to control private factories and set up its own, and women were summoned to enlist on a register for work. Strikes were prohibited. Promises were made, but never fully kept, that the women would receive decent pay with skilled workers on the same wage as men. By the end of the war, 4,285 controlled establishments and 103 state ones were in operation. The factories were spread all over Britain, particularly in east London and Glasgow.

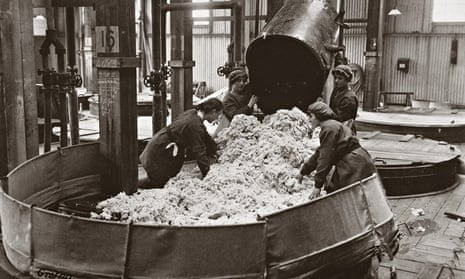

By far the largest was HM Factory Gretna in southern Scotland, which produced cordite – a complex system involving nitric and sulphuric acids, nitroglycerine, gun cotton, mineral jelly, alcohol and ether. The final product went into gun cartridges which, when fired, released the gases that propelled bullets and shells. The process was so dangerous that the various stages were undertaken in different buildings.

In 1915, the government built not only factories but also facilities for a new community at Gretna and Eastriggs. Houses and flats were constructed for staff and married couples, which were of such a high standard that they are still in use, and nearer the factories 85 barrack-type huts housed the female workers. A cookhouse, bakery, public halls, churches and railway lines were also built in a development that stretched for nine miles. Thirty thousand labourers, many of them Irish, were brought in to work on the construction sites. Remarkably, it was completed by mid-1916 at a cost of £5m.

By 1917, HM Factory Gretna was producing 800 tonnes of cordite a week – more than from all the other plants combined.

The 9,000 female factory workers included many former domestic staff and shop assistants. In his account of the facility’s development, Gordon Routledge highlights the visit of Arthur Conan Doyle, who wrote a glowing report on “perhaps the most remarkable place in the world.” Not only did it provide the army with essential equipment, it was also a community with good living conditions, a cinema and dance hall. Conan Doyle was particularly impressed by the “smiling khaki-clad girls who … stir the devil’s porridge”.

The women’s lives, however, were not as easy as sometimes portrayed. The suffragette and novelist Rebecca West admired the “pretty young girls” but also noted that they were contained on a site “ringed with barbed war entanglements and patrolled by sentries”. Their enjoyment of community facilities was limited by long working hours, sometimes stretching into the night. Their only free day was Sunday, and public transport was limited with trains to Carlisle cancelled because alcohol was on sale there. Even trips to see their families must have been a problem.

The women lived in huts consisting of a large living room with only wooden forms to sit on and small bedrooms with curtains but no doors. Residents complained of intense cold, particularly in the bitter winter of 1917.

Their earnings of between 30 shillings and £2 a week were almost certainly higher than their previous wages, but a substantial deduction was made for lodgings and meals.

They were also subject to a police service that stopped strangers getting in and the women getting out. They also searched every woman before work to ensure they were not carrying any item likely to cause an explosion if dropped into the porridge, particularly hairgrips and buttons. The discovery of any such item meant a fine of sixpence.

The women faced daily danger, and not just from explosions. Toxic fumes made many of them ill and sapped their energy. At times, workers were found asleep on the factory floor and deaths were not unknown.

The number of female workers in munitions factories nationwide is estimated at up to a million. They were often known as canary girls because their skin would turn yellow if it came into contact with sulphur. Routledge puts the number of deaths from poisoning and explosions at around 300, excluding those who died subsequently of illnesses caught at the factories.

Conan Doyle records that seeing the workers turned him into an advocate for votes for women, but the legislation of 1918 set the voting age at 31. Given that many of the munitions workers were young, their reward was delayed. The factories were closed soon after the war ended and unemployed women took second place to men seeking work after being demobbed. The female munitions workers showed courage and a readiness to toil that was overlooked during the war, and posters never portrayed the vital contribution they made to Britain’s victory. Neither was much written about their efforts after the war. A new museum exploring the history of HM Factory Gretna has been opened in Eastriggs near some of the remains of the factories and women’s accommodation. On the centenary of the opening of the factory, a public event should be held there to recreate the stirring of the devil’s porridge.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion