By Katherine Jacobsen

The COVID-19 pandemic has sent public health officials scrambling, the global economy into shock, and governments everywhere into crisis. It has also reshaped the way journalists work, not least because many authorities in many countries have cited the contagion as a reason to crack down on the news media.

Certain dangers will subside with time: a vaccine for COVID-19 should ultimately protect people, including journalists, from spreading or contracting the virus. But some of the measures put into place that restrict press freedom – whether intended or not — could continue well into the future, experts say.

It is possible that responses to the coronavirus could shift the long-term paradigm for journalism in unforeseen ways, in the same way the attacks of September 11, 2001, fueled the global expansion of anti-terrorism laws – and in turn, ushered in an uptick in the jailing of journalists that continues today.

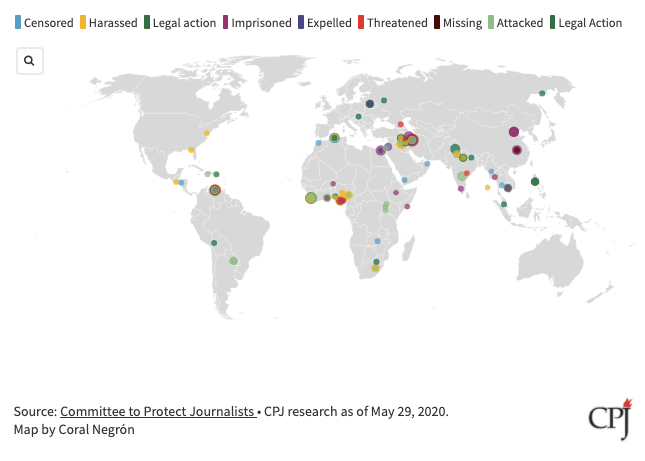

Global press freedom violations that CPJ has documented in relation to the pandemic can roughly be divided into 10 categories to monitor (with examples cited):

1. Laws against “fake news”

The pandemic has provided governments with a new excuse to wield laws criminalizing the spread of “fake news,” “misinformation,” or “false information” — and offered a reason to implement new ones. Over the past seven years, the number of journalists imprisoned on charges of “fake news” or “false news” has climbed, according to CPJ research.

Carlos Gaio, a U.K.-based senior legal officer with the Media Legal Defence Initiative, told CPJ that “fake news” laws will continue to spread as governments try to control messaging about the virus, affecting journalists and fact-checkers alike. “It’s a very complicated subject to outlaw something like that [and it] is very, very dangerous,” Gaio said.

Disinformation is a real problem, but these legal measures give governments latitude to decide what they consider to be false, sending a chilling message to critical journalists. In the U.S., President Donald Trump frequently disparages the media’s COVID-19 coverage and uses the term “fake news” when he disagrees with reporting, a strategy that CPJ has found effectively discredits the media and erodes public trust. It serves as a green light for authoritarians to deride and prosecute their own press.

- South Africa on March 18 criminalized disinformation about the pandemic with penalties that include hefty fines and jail time – a particularly worrying move since the country often serves as a regional model.

- Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, on April 6 made it illegal for media outlets to “transmit or allow the transmission” of “false information.” Violators could face up to six months in prison and fines up to $5000.

2. Jailing journalists

Arresting journalists has long been a tactic of authoritarian governments looking to silence critical reporting; at least 250 journalists were jailed worldwide at CPJ’s last annual count in December. With COVID-19 in circulation, imprisonment could be deadly; journalists are held in unsanitary conditions and forced into close proximity with others who could be infected. CPJ and more than 190 partner organizations have called on authorities worldwide to release all journalists jailed because of their work.

Nonetheless, arrests continue.

- In India, authorities in Tamil Nadu state arrested on April 23 the founder of SimpliCity news portal and accused him of violating the antiquated Epidemic Diseases Act and other laws. The website had alleged government corruption in food distribution efforts related to the pandemic.

- Jordan’s military arrested two journalists for satellite channel Roya TV on April 10 in relation to a report on worker complaints about the economic impact of a curfew.

- Somali authorities arrested an editor for Goobjoog Media Group on April 14 and accused him of spreading false news and offending the president’s honor after the journalist posted criticism on Facebook of the government’s handling of the crisis.

3. Suspending free speech

Some governments’ emergency measures have revoked or suspended the right to free speech for the duration of the emergency.

- Liberia’s constitution protects freedom of expression “save during an emergency” and affords presidential power to “suspend or affect certain rights, freedoms and guarantees” during a state of emergency like the one imposed April 11.

- Honduras on March 16 declared a temporary state of emergency that suspended some articles of the constitution, including the one that protects the right to free expression (though the government reversed that measure days later).

4. Blunt censorship, online and off

Authorities in several countries suspended newspaper distribution and printing in what they called an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19. Elsewhere, media regulators have blocked websites or removed articles with critical coverage.

- Jordan, Oman, Morocco, Yemen, and Iran all suspended newspaper distribution in March.

- Tajikistan blocked independent news website Akhbor on April 9, after it reported critically on the government.

- Russia’s media regulator, Roskomnadzor, ordered radio station Ekho Moskvy to take down an interview with a disease expert, and news website Govorit Magadan to remove an article about a local pneumonia death.

5. Threatening and harassing journalists, online and off

Government officials and private citizens alike have responded to critical reporting on the pandemic response with violence and threats. In places where the reporting environment was already hazardous, the situation has grown more fraught.

- Chechnya’s leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, threatened a Novaya Gazeta reporter after she wrote on April 12 that Chechens had stopped reporting coronavirus symptoms for fear of being labeled “terrorists.”

- Haitian journalists were assaulted by unidentified men at the government’s National Identification Office on April 2 as they investigated claims that the office was violating COVID-19 guidelines on social distancing.

- Ghanaian soldiers enforcing restrictions related to the pandemic assaulted journalists in two separate incidents in April.

6. Accreditation requirements and restricted freedom of movement

Authorities have restricted journalists’ ability to move about freely, such as if they want to report during curfews, or enter hospitals to get a first-hand account of health care. Sometimes the press is granted special access, but requiring members of the media to have government-issued press credentials allows leaders to decide who gets counted as a journalist.

CPJ research shows that this leaves open the possibility that they will exclude those not affiliated with major outlets or those who report critically on the authorities.

- Indian police assaulted at least four journalists in three separate incidents in Hyderabad and Delhi on March 23 as they transited to or from work during the lockdown, even though national authorities have stated that journalists are exempt from the restrictions.

- Nigeria required journalists to carry a valid identification card to move around certain locked down areas, including the capital Abuja, and designated only 16 journalists as allowed to enter the president’s villa.

7. Restricted access to information

Laws on freedom of information that allow journalists to request government data and records have been suspended. Government proceedings that journalists usually attend have moved online, with varying degrees of access for the press. In the U.S., Trump’s antagonism to journalists sets a poor example for U.S. state and local officials.

Gaio told CPJ that these trends are likely to persist. “[Governments] will make it more difficult for officials to provide information. Access to information will take longer, and it will make it more complicated for journalists to access public spaces because of infection risks,” he said.

- Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro on March 23 signed a measure into law that suspends deadlines for public authorities and institutions to respond to requests for information, and does away with appeals in case of denial. (Brazil’s Supreme Court overturned the measure on April 30, according to news reports.)

- United States governors and mayors have created a patchwork of access to press conferences around the country. In Florida, the governor on March 28 barred one reporter from attending a press conference after she asked about social distancing measures.

8. Expulsions and visa restrictions

In order to control the narrative of how the government is responding to COVID-19, some states are being inhospitable to foreign media, which in some places has traditionally enjoyed greater latitude than locals to report critically.

- China and the United States have been engaged in a tit-for-tat over journalist access since early in 2020. Among the developments: In February, China forced out three Wall Street Journal reporters, ostensibly in retaliation for a headline on an opinion piece about COVID-19. In March, the U.S. imposed a limit of 100 on the number of visas for Chinese state media; China retaliated by terminating visas for at least 13 U.S. reporters from The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal.

- Egypt expelled Guardian reporter Ruth Michaelson in retaliation for her report on March 15 that cast doubt on the government’s official statistics regarding the pandemic.

9. Surveillance and contact tracing

Governments around the world are monitoring mobile phone location data and testing or rolling out new tracking apps to follow the spread of COVID-19, according to news reports. the surveillance could imperil source confidentiality. The systems are introduced with limited oversight, and could endure long after the pandemic.

“There’s always a concern that emergency situations create new baseline expectations for what kind of surveillance the government is authorized to conduct. We certainly saw this through 9-11, but I think the same issue is presented here,” said Carrie DeCell, a staff attorney with the Knight First Amendment Institute in New York. “Actions that might be justified in that particular context certainly would not be justified once governments get a handle on this pandemic and once the crisis subsides somewhere in the near future.”

David Maass, a senior investigative researcher at the San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, agreed that once law enforcement is given a new technology, it’s difficult to take it back. “We’ve seen that today they’re using it for this very dangerous virus, but we don’t know what will happen later.”

- Telecom companies in Italy, Germany, and Austria are turning over location data to public health officials, though aggregated and anonymized; governments in South Korea and South Africa are monitoring individual cell phone locations, and Israel authorized security agents to access location and other data from millions of mobile phone users.

10. Emergency Measures

Authoritarian rulers can take an opportunistic approach to emergency measures that criminalize or restrict newsgathering activities, as CPJ has documented previously.

- Hungary’s parliament on March 30 approved a set of emergency laws enabling Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to rule by decree.

- Thailand introduced on March 26 a state of emergency that allows the government to “correct” reports it considers incorrect and allows for charges against journalists under the Computer Crimes Act, which carries five-year prison penalties for violations.

With many countries still under states of emergency that grant authorities power to rule by decree — and the virus only beginning to take hold in some developing countries – even more restrictions could be on the way.

Katherine Jacobsen is CPJ’s U.S. research associate. Before joining CPJ as a news editor in 2017, Jacobsen worked for The Associated Press in Moscow and as a freelancer in Ukraine, where her writing appeared in outlets including Businessweek, U.S. News and World Report, Foreign Policy, and Al-Jazeera.