This blog post has been written by the Ti Group, Access’s learning partner. It is based on interviews with 12 witnesses who were or are directly involved in the process as well as a review of all of the internal documentation as well as what is public. Where an opinion is expressed, this is the Ti Group’s interpretation of these sources unless otherwise stated. The TI Group would like to thank all of those who gave up their time for interviews and provided full access to documents.

Previously in the story of Total Impact… we learned that investing an endowment to make a difference as well as make a return happened because the Cabinet Office required it. Then we saw that the right people coming together mattered as much as the process and that they shared an energy and enthusiasm to do something different. So what of the process?

By the late summer of 2015, Access had a mandate to build a Total Impact approach to its endowment, and a capable team who were nonetheless aware that they weren’t the first to think about this challenge. The assumption was that it would probably be straightforward enough to call the people that had done it before and clone the best processes.

It didn’t turn out to be that simple.

Viewed from the vantage point of 2019, it seems obvious that the market wasn’t accustomed to something like Total Impact because there hadn’t been the demand. At the time, though, it was a bit of surprise that so few other foundations had explored Total Impact investing for their endowments. As mentioned last time, there were a few notable exceptions like FB Heron, KL Felicitas and Panahpur in the UK (remember that James Perry from Panahpur became chair of the endowment working group for Access and Martin Rich sat on its Investment Committee). However, the first two of these were in the US. Closer to home, others like Barrow Cadbury Trust and City Bridge Trust had begun experimenting with impact investing by carving-out a proportion (in their cases 5% or a little less) of their endowment as a test; something that was a rarity, but rich in learning.

The general scarcity of practice meant that if Access was going to do Total Impact the way it wanted to, in the context of a 10-year lifespan to spend its endowment as well as invest it, there wasn’t a format to copy: it was going to have to design this itself.

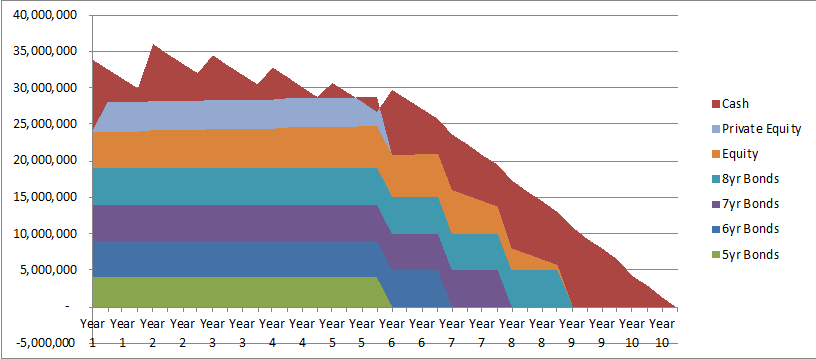

The exam question set by Cabinet Office in Access’s founding document was to invest the endowment for impact, protect the capital and keep it available for spending on programmes. That set the tone for the financial modelling of Total Impact and meant that things were pointing towards investing in bonds: charity bonds, preferably, with a safety-net of some cash available for unexpected demands from Access’s programmes. Equity or private equity, perhaps in property, would be a smaller proportion. This shaped the financial model built by Martin Rich (from the endowment working group) and Janie Oliver (from the executive team). The first graph was built for the £36m that was available immediately:

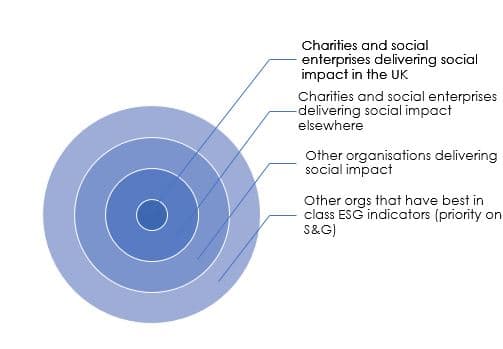

Attention then turned to the impact model: the challenges here were to represent the range of possible impacts from low to high, in line with Access’s mission to support charities and social enterprises yet to be reached by social investment; and the spectrum of risk in any impact investments.

The imaginative leap taken by the team was to represent these dimensions in one place, by drawing a bullseye, just like the one on a dartboard or at an archery competition. It looked like this:

Cash for programmes could be considered the fifth circle.

This disarmingly simple design included plenty of room for judgment and decision-making by Access and its future asset managers. This was a deliberate design feature, negotiated over several months of endowment working group meetings in the summer and autumn of 2015. As one interviewee put it, “Tackling an enormous system and getting the transparency was step one.” Another observed that “Lots of people start with ‘I can’t get everything in the middle so I won’t bother trying.’ [The bullseye means] You can still have some success even without getting everything in the middle.”

So the team’s hypothesis was that they would invest as much of the endowment as possible in the centre of the bullseye (tier 1) and fill up the other tiers if they couldn’t find enough deals with healthy enough returns that didn’t lock-up Access’s money for too long, because they needed it for their programmes. It was going to be a constant negotiation between risk, return, impact, and liquidity/length, bearing in need the mind for fast access to the money. Some members of the group were “worried about the breadth of choice of investments if impact was defined too narrowly”. Conversely, it was felt that this approach offered a balance, prioritising impact as well as allowing some flexibility.

It would later turn out that nearly 50% ended up in the bullseye but, at the beginning, nobody knew how it would turn out. The guidebook hadn’t been written yet.

The lack of a guidebook led Access to realise three things at this stage of Total Impact:

- It needed the right external asset manager – crucially one that shared its values – to pool their expertise and work together in this uncharted territory;

- It needed to keep the endowment working group, to sustain the values and intentions of Access as Total Impact evolved from a theory into a live experiment. (This would become the Endowment Investment Committee.); and

- It ought to distil its knowledge into an investment policy to guide an asset manager, and for anyone else to look at if they were interested. (Although it was not written at this point, the current version can be found here.)

As winter arrived in 2015, the search for an asset manager was getting started. It would turn out to be an interesting process.

Coming up next time…

The curious market and why £60m doesn’t always get you what you want.