In the middle of a field in South Carolina, Alethea Thompson closed her eyes and attempted to sense her way forward. Thompson, now 35, had spent years trying to find a spiritual home and had decided to try something new. This exercise was meant to teach her to “to trust in your ability to sense things and know that you’re not going to fall, you’re not going to get hurt,” she says. And was part of her training to become a Jedi.

After 12 years with the Force Academy, an online community that provides educational courses on Jediism, Thompson is today a Jedi master. She explains that the Force Academy and most Jedi organisations don’t prescribe strict rituals: there are no requirements on diet or clothing and no mass-style services. Jedis do, however, follow a code of ethics that centres on resisting negative emotions and promoting peace. They also believe in the Force – the ubiquitous energy field described in the Star Wars movies – and mindfulness is central to their belief system. “The foundation of who we are is meditation,” says Thompson. “I will meditate for about 30 minutes, but it’s not always the same kind of meditation. So, I don’t sit there all the time and just hum. Meditation comes in many forms and that’s what I try to teach in the community.”

To most people, Jedis are the priestly, lightsaber-wielding warriors that existed a long time ago, in a fictional galaxy far, far away. Their creator, the Star Wars writer and director George Lucas, seems to have been heavily influenced by real religions and philosophies such as Buddhism, Taoism, Kabbalah and the medieval code of chivalry. This gives verisimilitude to the Jedi religion in the films. However, the real-world religion arguably has origins in an internet prank almost 20 years ago.

In the run-up to the 2001 UK census, an email went round encouraging people to record their religion on the form as Jedi, insisting that, if 10,000 people were to do so, Jediism would become a “fully recognised and legal religion”. “Do it because you love Star Wars ... or just to annoy people,” the email read. In the end, 390,127 people did just that; in Brighton and Hove, 2.6% of census respondents said they were Jedis. John Pullinger, the director of reporting and analysis at Britain’s Office for National Statistics, said at the time the campaign was quite helpful. “Census agencies worldwide report difficulties encouraging those in their late teens and 20s to complete their forms. We suspect that the Jedi response was most common in precisely this age group.”

Yet among the hundreds of thousands of pranksters were people who truly believed they could feel the Force. Since the census, various attempts have been made to codify Jedi beliefs into a coherent religion, such as the Church of Jediism, founded by 20-year-old Daniel Jones in 2006 in Anglesey, Wales.

But with its roots in a film aimed at children, Jediism is wide open for mockery. For instance, followers have to explain that they don’t worship Yoda and, in fact, spend most of their time striving for spiritual growth and self-improvement rather than trying to shoot lightning bolts from their fingertips.

Today the UK Jedi community is estimated to have about 2,000 members – similar to the number of Scientologists in the country. However, their sincerity and numbers didn’t sway the Charity Commission, which in 2016 rejected an application for charitable status from the Temple of the Jedi Order, a Jedi organisation started in Beaumont, Texas.

This rejection may be just as well, as many Jedis consider Jediism a philosophy rather than a religion, a spiritual operating system on which any religious programme can run. Followers say you can be a Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Christian or even an atheist Jedi.

Thompson herself had a complicated journey to Jediism. Her early childhood was difficult and she was taken into foster care. After she returned to her mother’s home a year later, she was raised as a Catholic. But she became disillusioned after learning how the church regarded Mary. “It bothered me that this belief system would say you only worship one deity, but they treated Mary like a goddess,” she says. When she was 13, Thompson decided to worship the Sumerian gods Inanna and Enki. Then a close friend introduced her to the Force Academy.

There was one sticking point: “I hate Star Wars!” she says. “I felt like it was a Western space opera.” She was convinced only after hearing that the Force Academy aims to make Jediism compatible with other faiths.

Today, Thompson credits the spiritual practise with making her more tolerant, contemplative and empathetic. The Jedi, she says, had a “solid plan” on how she could become a “helpful force in the world”.

Others say it has even saved their lives. Vishwa Jay, 45, lives in Salt Lake City, Utah, and is a teacher of Buddhist philosophy, as well as the founder of a Jedi school. His early life was chaotic; he was taken into care aged seven and, before turning 18, had lived in five children’s homes and had more than 70 foster placements. This unrelenting displacement meant Jay emerged as an angry young man without meaningful relationships. His anger got him into fights, but he says even this was because he was trying to connect with people. “I got into underground fighting. Suddenly, I had friends for the first time and I didn’t know how to handle it.” Jay was put off the bare-knuckle scene only after an opponent attacked him with an aluminium baseball bat.

In his early 20s, Jay got in trouble with the police. He ended up going to see a Hindu swami called Mrs Stone. “I tend to try and be fairly rational about things. I was having a hard time accepting the reality of anything that she was trying to teach me on a spiritual level,” Jay explains. Stone asked him what he held sacred. “Being the rather smart ass that I was, I said Star Wars. She said: ‘Star Wars, hmm, that’s a great place to start.’ Immediately, at that moment, I knew I was doomed,” he says.

Jay began by studying the philosophy in the films and meditating. “One of the things that I learned from the Jedi philosophy was that being emotionally stable means facing the darkness within you. One of the foster homes I was living in had farms. And one of the things they do is take cow manure. After a while, it turns into fertiliser. So, the way that I explain it is you have to work through all of your bullshit in order to get something to grow.”

Jay, now a father of five, is no longer an angry young man using fists to make friends. He says much of his new happiness is down to Mrs Stone. “I’m pretty sure that I would have ended up in the grave by now because I had no knowledge of myself. I had no real concern about anyone other than myself.”

Jay promised his partner, who is not a Jedi, that he would not steer his children to Jediism, although his eldest daughter has found it herself. “She decided that, since it worked for me, it will probably work for her. In the last year she’s started learning a bit about the philosophy.” Does his Jedi Zen help, looking after five kids? “It does. Most people would be completely off their nog just trying to keep up.”

Jay H Tepley, 38, is a meditation teacher based in London. Before she had even watched the films, people called her a Jedi. “Because of mind mastery. I teach people to make their minds stronger and repel other people’s mental influence. I teach people to become better, stronger versions of themselves,” she says.

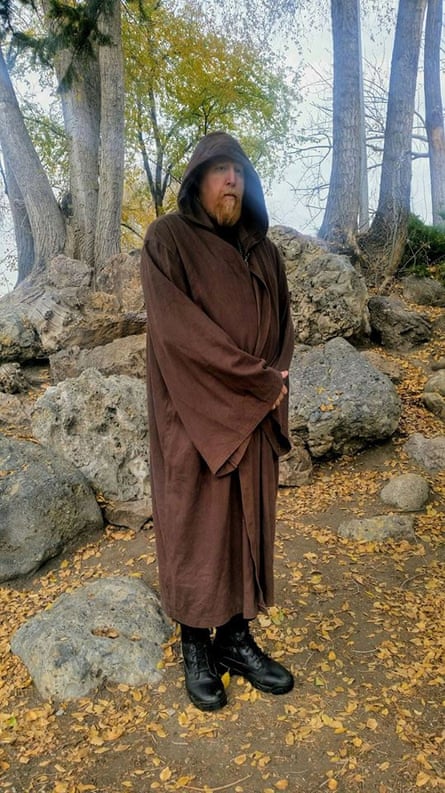

Is she a real Jedi? “Well, it depends what you mean. I’m not a Jedi in this world’s understanding; in terms of people being fans of the films and just dressing up in some peculiar way. I’m more of an actual Jedi from the film. If it were possible for them to travel here, they would recognise me as one of them.” This is not to say she doesn’t wear robes and, as well as teaching meditation, she teaches fencing at her lightsaber club. “Fencing is a great way of training your muscles, your focus and your sense of balance at the same time,” Tepley says.

A true Jedi is never without their lightsaber. After all, in Attack of the Clones, Obi Wan Kenobi tells Anakin Skywalker: “This weapon is your life.” Everett Ratcliffe, who goes by the Jedi name Arisaig Winterthorn, concurs. “I use a lightsaber because it’s really, really fun to use and it gets me out there every single day.” Ratcliffe, 26, is from Canada, but lives in Loughborough, Leicestershire. He discovered Jediism after leaving the Canadian army. “When I came to the Jedi path, I was using a cane to walk from an injury acquired in training during my time in the forces. I was fat, I hated myself and my mind was slipping as my life lacked direction. Now, I’m healthy,” Ratcliffe says. After recovering from his injury, Ratcliffe began practising lightsaber flow, a fencing form that entails spinning a sword or staff in intricate spirals. “It’s really intensive on the body and there’s just so much to learn to keep getting better at it.”

In the Star Wars films, the Force is the supernatural energy that allows Jedis to levitate objects, confuse Stormtroopers and attack people from a distance. Among followers of Jediism, the Force is interpreted in many ways, but most consider it a metaphor rather than something that helps them choke people like Darth Vader. For Ratcliffe, it is an omnipresent energy field. “I gave myself to the Force and the Force gave me everything,” he says. Can you feel this Force? “Of course. Anyone can. Every time you drink a glass of water you’re feeling the Force. Anything that can be experienced is an experience in the Force.”

But he says: “You ask 10 Jedi, you’ll get 10 different answers.” He is not wrong: for Tepley, the Force is the energy that underlines our entire existence; Thompson thinks it accounts for miracles; Jay believes it might have been responsible for the big bang. Richard Sroka, a programme analyst from Portland, Oregon, says the Force feels like a wellspring. “It feels like being a lot more alive, a lot more energetic,” he says. “You’re not worrying about tomorrow, you’re not worrying about yesterday. You’re living precisely when you are.”

Like Jay, Sroka struggled with anger, and the nostalgia he had for the films drew him to Jediism. “It’s the first thing that clicked,” he says. After immersing himself in Jedi philosophy, Sroka felt better able to control his temper. “When I start to feel angry, I take a step back, view where it’s coming from, identify what’s causing it and find the solutions to it. That’s where a lot of my connection to Jediism begins. It also taught me that sometimes you’ve got to disengage; you’re not always going to be able to get through the situation.”

Should we be mocking this belief system that sprung from our local multiplexes? Speaking to Jedi followers, it becomes clear that the lessons Jediism teaches are things that can be learned at Sunday school: help others, help yourself, embrace the light and resist the dark. In other words, be righteous and resist temptation. Sroka is philosophical about the fact most people won’t take it seriously. “It came from a movie and people don’t quite get it and that’s fine,” he says. Yet, he points out, that doesn’t mean it cannot help people. “When I go to work out, I have the mental image of Kratos from God of War,” he says referring to a popular video game. “Am I going to be able to hold two axes and do all those crazy stunts? Am I going to have those giant muscles? No. Am I going to have a great beard? Probably not, but if that’s what gets me up and moving then why is that a bad thing?”