The Doctors Who Bill You While You’re Unconscious

A fifth of U.S. patients get surprise bills from surgery—even if their surgeon and hospital are in-network.

Let’s say you need to get minor surgery, such as repairing some torn knee cartilage. If you have insurance, you would probably call the hospital or your insurer ahead of time to be sure that the hospital was “in network” with your insurance. If you’re extra savvy, you might double-check that the surgeon who will be operating on you is in-network, too.

I should be good, you might think. You reason that you won’t face any unexpected charges beyond your insurance’s co-pay, because the point of an insurance network is to funnel you to doctors and hospitals that your insurance will cover. But in fact, it’s more complicated than that. Americans often get staggering bills from providers they didn’t realize would participate in their surgery.

Many health-care horror stories begin with the receipt of this kind of “surprise bill”—a bill, often in the thousands of dollars, that a patient wasn’t expecting, and which often reflects the difference between what the provider believes it should be paid for the service and what the insurer actually paid them. These bills can accrue interest and end up on your credit report. Debt collectors can hound you to pay in unusual ways, and even garnish your wages. You often can negotiate with the hospital to reduce your payment, but that process takes time and skills that not everyone has.

A growing body of research suggests that this nightmare scenario is fairly common for Americans. And now, a new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association has found that surprise bills might be even more common than previously estimated: They happen about a fifth of the time that a patient has an elective surgery at an in-network hospital with an in-network surgeon. Having a surprise out-of-network bill raised the total bill by an average of $14,083. The dollars racked up while many patients were unconscious, and an out-of-network specialist simply walked into the room.

For the study, the authors looked at 347,356 people nationwide who were insured with a major private insurer. (The authors declined to name the company.) By reviewing bills from seven common elective procedures undergone from 2012 to 2017, including the aforementioned knee-cartilage procedure and hysterectomies, they found that the surprise bills came most often from anesthesiologists, who put patients to sleep before procedures, and surgical assistants, who do everything from aid in an operation to check on the patient afterward. Though the hospital might be in-network, these specialists might not work for the hospital, but simply treat patients there. The out-of-network surgical assistants charged more, at $3,633 on average, than did the anesthesiologists, at $1,219.

To the University of Michigan researcher Karan Chhabra, the lead author of the study, the most surprising thing is that surgeons can often choose their own assistants, but not their anesthesiologists. So why might surgeons pick out-of-network surgical assistants? “My hope is that it’s an accident,” Chhabra told me. “[Doctors] don’t always talk about which insurance everyone accepts.” Of course, most doctors are acting in good faith, but, he added, “my concern is that in some cases it might be happening intentionally to sort of exploit patients.” For example, surgeons might be teaming up with out-of-network assistants, and vice versa, to get more money from patients.

Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told me that though this study highlighted anesthesiologists and surgical assistants, surprise bills can also come from out-of-network pathologists, who analyze tissue and blood samples, or radiologists, who examine X-rays and MRIs. No matter who the surprise bills come from, “you don’t pick these people. You don’t know them,” Pollitz said. “You learn their name when the bill comes.”

The results in the new JAMA study are similar to, though slightly higher than, findings from the Kaiser Family Foundation. The health-care nonprofit recently found that about 18 percent of emergency visits and 16 percent of inpatient admissions result in surprise out-of-network bills. People who go to the hospital with a heart attack are especially vulnerable to surprise bills, it found.

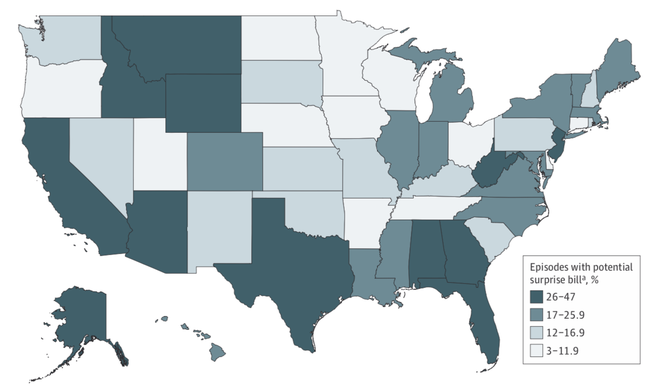

The surprise bills were also more likely to come if there were surgical complications, perhaps because as the procedure grows more complex, more people get involved in treating it. The risk of getting a surprise bill was higher on Affordable Care Act exchange plans compared with other plans, possibly because Obamacare plans have so-called narrow networks, with fewer participating doctors to keep costs down. There was also some variation among the states: Alaska had the highest rate of surprise bills, at 46 percent, and Nebraska had the lowest, at 3 percent.

It’s hard to know what’s behind the variation in surprise billing among the states. It could have something to do with the number of physicians in an area or the percentage of them that take a given insurance plan, Chhabra said. It could also have to do with venture-capital companies investing in physician practices, Pollitz said, and reasoning that “if you don’t accept many or any insurance networks … you can bill whatever you want.”

The data gave Chhabra a bleak impression of the U.S. health-care system. “It’s way too hard for a well-intentioned patient to come out unscathed,” he told me. “The way we set the system up is really putting patients last.”

Legislation is making its way through Congress that would put a stop to these bills. For care at an in-network hospital, the legislation would make it so that out-of-network doctors would have to be covered, and patients would pay the amount they would regularly pay for in-network care. President Donald Trump has expressed support for this measure, but doctors’ groups are still quarreling with insurers over how much exactly they would get paid under this proposal.

The new study was accompanied by an editorial by Karen Joynt Maddox, an assistant professor at Washington University School of Medicine, and Edward Livingston, the deputy editor of JAMA, calling on surgeons to “speak out” against surprise billing, and for Congress to pass the surprise-billing legislation. In the meantime, the next time you get surgery, it might be worth asking ahead of time if every provider who treats you will be in-network. It might not prevent a giant bill—but at least you won’t be surprised.