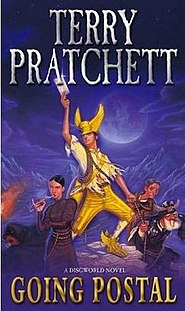

I have to warn you now that this is going to be one of those posts in which I blather on about how many different types of wonderful Terry Pratchett’s novels are. Going Postal is Pratchett at the peak of his powers. Incidentally it also made by far the best television adaptation, which I think successfully captures the spirit of the novel and retains almost all the central ingredients.

Going Postal is a devastating attack on the rapacious form of asset stripping capitalism. In the novel the clacks, the Discworld telegraph system, has been taken over by an aggressive consortium of bankers interested only in squeezing profit from their new enterprise. To this end they refuse to invest in maintenance of the system, cut corners, and put the safety of their staff at risk. The chief engineer Mr Pony, who stays with the company, knows the lives of his workers are being put at risk but protects himself with copies of warning memos. He is a deeply sad figure, but all too recognisable in late-stage early 20th century capitalism. Pratchett dismantles surgically the smoke and mirrors behind high-finance:

“But, in truth, it had not exactly been gold, or even the promise of gold, but more like the fantasy of gold, the fairy dream that the gold is there, at the end of the rainbow, and will continue to be there forever – provided, naturally, that you don’t go and look. This is known as finance.“

So what happens? Moist von Lipwig, a consummate swindler, is hanged for his crimes. His still living body is recovered from the scaffold, resuscitated and taken before the Patrician. Vetinari presents him with a choice: become Postmaster General of the city’s postal service or death. Moist takes the job, intending to run away at the earliest possible opportunity. However, his probation officer, a golem named Mr Pump (after his former occupation), brings him back to Ankh-Morpork, where Vetinari explains escape from a golem is impossible. So the Post Office it is.

The scale of the challenge is soon revealed. The Post Office has not operated for many years, and the building is full of undelivered mail and pigeon dung. Four previous recently appointed Postmasters have died in suspicious circumstances. Of the many portraits in Going Postal one of the most relevant (although I think they are all relevant) is of Reacher Gilt, the chair of the Grand Trunk Company which runs the clacks. Gilt is a financial pirate who operates in plain sight – he even has a parrot that squawks “twelve and a half per cent” (= pieces of eight, not the worst joke in the novel). Gilt has a penthouse office in Tump Tower and has ambitions to become Patrician one day – see what Pratchett was hinting at there? It is quickly apparent that Gilt is the villain of the piece, is behind the deaths of the previous Postmasters, and plans to remove Moist as soon as possible.

This is just the beginning of an extraordinarily action-packed novel – there’s a wonderfully rich cast of junior characters such as pin-collector Stanley Howler; Sachrissa Cripslock, reporter for the Ankh-Morpork Times (first introduced in The Truth); and Anghammarad, a nineteen thousand year-old golem waiting for the end of the world. There’s a fire, a visit to the Mended Drum, a race to Genua, and guest appearances from the Watch and the wizards of the Unseen University, to mention just a few highlights. Romance is provided by another of Pratchett’s amazing strong women: golem-rights activist and chain smoker Adora Belle Dearheart. It’s all utterly wonderful. Moist is another brilliantly realised creation in all his complexity and carries the weight of the narrative effortlessly. The moment he realises his responsibility for Adora’s loss of her job (which the television adaptation made even more dramatic in a very effective edit) is extraordinary.

This is also the Discworld novel where the GNU tradition originates. John Dearheart, murdered brother of Adora, is remembered by his colleagues on the clacks by a piece of code – “GNU John Dearheart” – which echoes his name up and down the lines. “G” means that the message must be passed on, “N” means “not logged”, and “U” means the message should be turned around at the end of a line. (This is of course a tech joke: GNU is a free operating system, “GNU’s not Unix”.) The code causes John’s name to be repeated indefinitely throughout the system, because: “A man is not dead while his name is still spoken“, a phrase with so much more resonance since Sir Terry’s passing.

I know I have said this many times before, but Pratchett is a profound moral philosopher and this novel is over-flowing with insights into the human condition:

“There was no safety. There was no pride. All there was, was money. Everything became money, and money became everything. Money treated us as if we were things, and we died.

In fact, I am giving serious consideration to starting my own minor religion based on the words of wisdom found in Going Postal alone. If you read a sentence like this in a book of philosophy you would almost certainly nod your head in agreement and appreciate the author’s wisdom and sagacity;

“all freedom is limited, artificial, and therefore illusory, a shared hallucination at best. No sane mortal is truly free, because true freedom is so terrible that only the mad or the divine can face it with open eyes.

I used to always say Night Watch was Pratchett’s finest novel – having re-read Going Postal I am no longer quite so sure.

Yes, I loved this one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was an incredible read. So ridiculously fun and with an amazing cast of characters. I absolutely loved it! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of his best

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Book review: Making Money (Discworld 36) by Sir Terry Pratchett, 2007 – The Reading Bug

Pingback: Book review: Raising Steam (Discworld 40), by Sir Terry Pratchett, 2013 – The Reading Bug