New songs from your favorite artists come out all the time -- and we preview them down below!

New songs from your favorite artists come out all the time -- and we preview them down below!

Over delicate acoustic guitar finger-picking and a lush orchestral score, Linda Ronstadt sings, “’cause I’ve done everything I know to try and make you mine and I think I’m gonna love you for a long long time.”

It’s a line from her 1970 single, Long, Long Time, her first hit as a solo artist.

For this writer, had she only recorded this exquisitely beautiful and haunting song Linda Ronstadt’s place in music history would be assured. But to the delight of music fans worldwide, this was only just the beginning of a storied and wondrous musical journey.

Sales of over 100 million records…winning collaborations with the likes of Neil Young, Randy Newman, Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton, Aaron Neville, Johnny Cash, Gram Parsons, Rosemary Clooney and Frank Sinatra … shelves groaning with every prestigious music award imaginable …

Over four decades of music making, Linda Ronstadt is a consummate song stylist who remains one of popular music’s greatest and most beloved artists.

Blessed with one of the most extraordinary voices in popular music, Ronstadt drew from a deep well of influences ranging from Mexican folk music to Hank Williams, opera to the Everly Brothers. From the sun-kissed country rock splendor of 1974’s Heart like a Wheel to the punchy new wave sass of 1980’s Mad Love, the elegant Great American Songbook craftsmanship of 1983’s What’s New to her all Spanish album, 1987’s Grammy Award winning Canciones de mi Padre, Ronstadt’s wide-screen musical education played a significant role in helping to inspire, shape and inform her career choices.

By the turn of the ’70s she was the most popular female artist of the decade. Multi-platinum albums, a raft of hit singles, sold out concerts–she graced the covers of both Time and Rolling Stone magazine–Ronstadt literally wrote her own ticket, essaying a wide swath of musical styles and genres numbering country, pop, rock, R&B, jazz, new wave, American songbook standards and mariachi.

Time Magazine February 28, 1977

And the one common thread through all of her music? Her peerless interpretative skills, fearless versatility and hard fought integrity.

Now retired from recording and touring as a result of being recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which has tragically robbed her of her singing voice — she released her last album in 2006 and performed her last show in 2009. At age 67, Ronstadt is content in her life, reveling in the joy of parenthood and raising her two children.

She might have vanished from the public eye but that spectacular, rich and robust voice is never far from the airwaves. Her new autobiography, Simple Dreams, chronicles her remarkable life revealing how the fledgling singer was transformed into one of the most popular and enduring artists of her time. Ronstadt wrote the book herself without the aid of a ghost writer and strewn throughout its pages resounds the strong, powerful and authentic voice of a woman who bravely forged her own artistic path.

Ronstadt was kind enough to speak with Rock Cellar Magazine for a feature interview – enjoy our chat below.

Rock Cellar Magazine: Was there anything you learned about yourself during the process of writing the book?

Linda Ronstadt: Well, I learned not to procrastinate. I used to be a procrastinator and this changed all that. (laughs) I wrote every word, for better or for worse. (laughs)

I don’t know what I learned about myself doing the book. Thinking about it, I guess I learned that I have a terrible memory and that I often remember things where events are condensed and dates are very fuzzy to me. I’d remember someone dying five years before she did. They say they have been able to create false memories in mice.

I’m not inclined to brag, as you may have noticed after reading the book. I know certain things are important to readers that you need to touch upon…like when you’re struggling and then you have to describe how you came to succeed.

I remember clearly somebody showing me that You’re No Good was number one on the Billboard pop chart, the Billboard country chart and the Billboard rhythm and blues chart. It turned out it didn’t happen and I’ve corrected it in the book.

I remembered it so clearly and now I think it probably happened but I don’t think it was Billboard magazine; it might have been a local chart. But I also remember thinking what good does this do having this kind of major success because I didn’t care for the way I sang You’re No Good. I didn’t think the vocal was any good.

I remember being disappointed in that so its success was a false success for me.

The success of You’re No Good was not something I was proud about but was rather it was something I was so disappointed in. (laughs)

RCM: That’s surprising to hear. Why didn’t you think the vocal on that song passed muster?

Linda Ronstadt: I was tired and we’d been working on You’re No Good for a long time. I was also a little tired of the song anyway because we’d been doing on stage. I sang it all day and my voice was all worn out and my rhythm was a little off. I just didn’t like it and didn’t like my phrasing on it.

RCM: In your book you state “Our parents sang to us from the time we were babies.”

Linda Ronstadt: I come from a really musical family. Everybody sang in my family. They weren’t doing it on a professional level and weren’t as good as Richard and Linda Thompson’s kids or the McGarrigles but we sang in tune and we sang in time and we sang the things we loved and we sang with each other.

I think it’s really important for people to do their own music. I think we’re very eager to delegate our artistic endeavors and experiences to professionals, like we don’t do our own drawing and painting. We don’t do our own dancing.

Unless you live in New Orleans no one in this country dances (laughs).

It’s a shame. It’s fine to have heroes. It’s good to have people like Adele or Pink or whoever’s a good singer but you need to have your own thing too.

RCM: Did it take you a while to find your own voice?

Linda Ronstadt: It took me about ten years. I started sounding like myself in the late ‘70s. It wasn’t until I actually went to Broadway and came back that I really landed on my voice and oddly enough it was with the Nelson Riddle stuff. I can sing rock and roll and I had a successful career doing it but I wasn’t as personally invested in that as I was singing those standards. Those songs are exquisite works of art; they’re beautifully crafted and are written for singers. (laughs)

And also, the person that I was and the way that I was raised didn’t make me part of that rough and tumble world. Was I there? Yes. Did I try drugs? Of course. Did I like it? Not particularly. It just wasn’t who I was. You go to where you need to go to get music. I always made sure I had a musical reason to be hanging around and I always made sure I had a ride home. Those were the two essentials. (laughs). And you get good songs that way.

RCM: Singing in private and at family functions is one thing, putting yourself out there to sing in public is another. What compelled you to go that route?

Linda Ronstadt: I just wanted to be able to do music all the time. So if I had a job at a bank or had a job driving a cab or teaching English or nursery school I wouldn’t have very much time to do music. From an early age, I was able to get paid singing, not a lot of money but it was enough to eat. I was able to get by singing in whatever kind of a venue I could find to play. I mean I wasn’t fussy, I played in pizza parlors and beatnik dives and all kinds of strange places. I played The Insomniac down in Hermosa Beach, which is now thankfully a parking lot. We played wherever we could get a job and we were lucky to get jobs and happy to get jobs.

Playing a place like the Troubadour in Hollywood was a really big deal. We probably would have paid to have played there. Now you have to pay to play clubs but not back then, we certainly couldn’t have afforded it in those days and thankfully they didn’t have that policy then. They paid us starvation wages but we somehow got by.

RCM: Speaking of the Troubadour, in the late ‘60s you were part of that musical nexus which spawned so many burgeoning artists. How did that club figure into your musical development?

Linda Ronstadt: The Troubadour was probably a less sophisticated version of café society. It actually wasn’t that unsophisticated; there were plenty of sophisticated people coming in and out of there. But it was kind of like a version of the West Coast casual café society. So it was a café in the true sense of the word where there were a lot of artists coming and going there. You’d get something to eat, you’d get a drink, you’d hear a story, and you could have a soft shoulder to cry on, whatever. People really influenced each other in that place. That was a little microcosm for a while where people could see performers in a small place that was sympathetic to music.

After everybody got to be such big stars and music started going in those huge arenas we just didn’t influence each other as much.

All the musicians were surprisingly supportive. Yes, there was a lot of competition and there was a little bit of cut throat activity. I think it shows a lot in the work of the Eagles and Jackson Browne and JD Souther; I knew all of them very well. They were there to support each other. They really did help and encourage each other. They wrote together and they really tried to get the best out of each other and that was impressive because they could have just have easily sliced each other down. I’ve been around situations where everybody was trying to be hipper than thou and pull all of the hip people into one corner of the room and laugh at all the people that weren’t hip.

There was a lot of that going on in the ‘60s around Bob Dylan and around a lot of those English bands. That was sort of the attitude of wanting to get with the hipper side. But I never bought into that. It was so competitive and all about looking down at other people and trying to trip them up and make them look bad. Everybody’s in there at some level just to learn and it gets down finally to, “Can you pull your weight? Can you do the job at hand? Can you make up that harmony or make up that lead lick or figure out that arrangement?” And for me, that’s what really counts, not who’s hipper. (laughs).

Rolling Stone magazine really encouraged that attitude. It was kind of Puritanism and I never liked it.

RCM: Tell us how you found the Mike Nesmith song Different Drum, which became your first major hit with The Stone Poneys.

Linda Ronstadt: See, I had these bluegrass records by the early bluegrass guys and then there were these New York musicians who really loved that music and tried to emulate it like the Greenbriar Boys who used to travel with Joan Baez. They were really wonderful. Their lead singer was John Harold and he was a good singer. In fact, I first heard Different Drum on a record by the Greenbriar Boys and I didn’t know that Mike Nesmith had written it. I knew Mike Nesmith and knew he was a very talented guy but didn’t realize it was his song until after I learned it and had fallen in love with it.

That song had a sentiment that I wanted to say. It was something I wanted to proclaim for myself, which is how I pick all the songs I sing. I picked it and loved the way he sang it and I also loved his treatment of it, which was acoustic. The Stone Poneys were into folk rock and I was trying to make sure the song had a little bit more than just a traditional approach to it. Different Drum wasn’t even a traditional song but already they’d (Capitol Records) taken it and made a synthesis. I wanted to make it a little bit more mine and more of that California thing.

Our producer, Nik Venet, hired this arranger, Jimmy Bond, who’s a darling man, very smart, a good jazz musician and a good arranger for pop stuff. But I was just shocked by the treatment they gave Different Drum.

I hadn’t evolved that arrangement in an organic way, which was the manner in which I usually approach music. I hadn’t done it with the group but had chosen it as a song for myself and I thought it was a hit. I wanted to recut it but Nik wouldn’t go for it.

The version of Different Drum that was a hit was the second time we cut it. We’d cut it first with just guitar, a mandolin and acoustic bass. I didn’t think that version was strong enough so we decided to recut it but then we recut it with the orchestra, which was shocking to me. We only ran through two takes of it and that was it.

We used some players from the Wrecking Crew on that–Don Randi was on harpsichord and Jimmy Gordon on drums. When you had expensive musicians on the clock you didn’t keep them long. Those players in the Wrecking Crew were so good you could book half a session and that would be enough time to get what you wanted recorded properly. We used them on Different Drum because they were the first call studio guys. I didn’t know that world at all; I’d just come from Tucson and I had no clue. I’d just played music with the people that I knew; I didn’t know there were other people you could hire. I was worried about it. It’s not that they weren’t good players–my God, they were vastly better players than we were but they hadn’t evolved along our same path.

They hadn’t absorbed the same musical idiosyncrasies that we had so I felt the recording of Different Drum didn’t sound like us. And I was right; it didn’t sound anything like us. (laughs) But Different Drum was a hit and as it turned out, the way The Stone Poneys sounded wasn’t destined for success.

I felt the songs that Bobby Kimmel was writing for The Stone Poneys were songs that expressed more of his sentiment than mine. He was writing about his own feelings (laughs), which is exactly was he should have been doing. Bobby was a very sensitive writer and I did enjoy his material. Anyhow, so I found Different Drum and I also found a bunch of Laura Nyro songs that I wish I could have discovered ten years later when I actually knew how to sing because I would have loved to have had a shot at those songs. She was an incredible writer and a really first rate singer. She was really an original.

I also found a Jimmy Webb song called Where’s the Playground, Susie and I wanted to change the title to Where’s The Playground, Baby.

Funnily enough, the girl, Susie, who the song was written about wound up marrying my cousin Bobby and she now sings in a band with Bobby Kimmel from The Stone Poneys. (laughs) It’s so funny how all those things come around but I never did get to record that song.

RCM: While growing up, you enjoyed the rich diversity of top 40 radio with acts like Louis Armstrong playing next to The Beatles, Paul Revere and the Raiders alongside Dean Martin. Do you think that diversity impacted on the various genres you so effortlessly tackled through your career?

Linda Ronstadt: Oh, it had a tremendous impact on me. My background at home had that kind of diversity so I resonated with it. We listened to all kinds of different music when I was growing up. My father and mother loved a lot of different types of music. So when I turned the radio on and heard all these different kinds of artists, it had a big impact on me and I’m sure influenced me later in choosing to record all kinds of different styles of music.

RCM: The Stone Poneys opened shows for The Doors and you got to know Jim Morrison.

Linda Ronstadt:

Jim [Morrison] was very soft spoken, quiet and very moody. When he was not drunk he seemed nice enough but as soon as he began to drink he really got very wild so quickly, which was frightening to me.

I’d never been around that kind of heavy drinking and seeing someone like Jim Morrison – who had such a personality – change when he drank was very frightening to me. It was scary to witness when someone seems one way and then they turn into someone else. I was very young and it frightened me.

I used to watch The Doors play every night. They were great. They were a power trio and were one of the best bands I’d ever heard at that point. I thought they were fabulous. I didn’t much care for Morrison’s singing even before we toured with them. The first time I saw them play live was at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go and I think they had just recorded Light My Fire and it hadn’t become a big hit yet. I was very impressed with the group and said, “They’re gonna be a big hit band!” But to be completely frank, I thought if they’d gotten a better singer they’d be a much better group. (laughs)

RCM: Reading your book, I was surprised that you seemed uncomfortable making the move from the Stone Poneys to a solo career.

Linda Ronstadt: You’re right, I was uncomfortable for the simple reason that I never wanted to be a solo artist. I was always trying to get back in a group. That’s why I sang with Dolly (Parton) and Emmylou (Harris) and that’s why I sang with Aaron (Neville). I love singing with other people. I can do things with my voice with other people that I could never do by myself.

RCM: Why is that?

Linda Ronstadt: Because whatever the colors and the textures are in someone’s voice, you try to reflect them, you try to mash ‘em, you try to embellish them and you try to augment them. Those all become things you wouldn’t come upon on your own. It’s very intuitive. Art is like water; you’re just kind of reflecting everything that’s around you. So somebody comes in with sky, somebody comes in with the earth, somebody comes in with the flower and you’re just reflecting all those different things. You’re not thinking about it. It’s not a conscious process; it’s a collaborative process. So when I sing with Emmy I make sounds with my voice that I’d never make with anyone else or on my own. Same way with Aaron. My God, Aaron got stuff out of me vocally that I thought I could never do!

RCM: You were nominated for a Grammy for Best Contemporary Vocal Performance for the song Long, Long Time from the Silk Purse album. It’s a beautiful song and was your first big hit as a solo artist.

Linda Ronstadt: In those days I chose whatever songs I wanted to do and the label paid the bill and I sang it. Then if your records weren’t a hit they didn’t pay the bill the next time. That’s how that works.

I couldn’t get into that way of thinking.

I was very happy I got a hit with Long, Long Time so I could keep recording but I never picked stuff solely because I thought it was a hit. I picked that particular song because it just hit me right between the eyes.

I thought it was one of those amazingly true songs.

Ironically, I ran into the woman that song was written about at the hairdresser out here in Marin County where I get my hair cut (laughs). I really like Long, Long Time but I’m not proud of my vocal on that song. But later on I learned how to sing it better live. I think I found a live version where I think I sang it a lot better. Back then I was doing a funny kind of vibrato thing with my voice; it was kind of like a Billy Goat vibrato and I didn’t like that so much.

I listen to songs of mine from back then and go, “Why was I doing that?” I don’t think there’s anybody alive who does music that doesn’t do that. You look back at what you’ve done and think, “That sounds so weird.”

I can think of the best Jackson Browne song I’ve ever heard and when I tell him he goes, “I shouldn’t have written that line that way, I can write better songs now.” Who knows whether it’s better then or now but Jackson is one of those people who wrote really great songs when he was sixteen. (laughs) He wrote These Days when he was that age and that’s amazing.

RCM: Have you always been hard on yourself as a singer?

Linda Ronstadt: I’ve never liked any of my records. I just hear the vocals and they make me shudder.

I always say there are three elements that go into music. There’s story, there’s voice and there’s musicianship. Some people are stronger in one area than another. I was strong on story and strong on voice but not as strong on musicianship but that came later and I learned after a while. I thought I just couldn’t learn because I didn’t have it. I didn’t realize people spend years in conservatories honing these skills. (laughs) And I never did any of that. I couldn’t read music and wasn’t very proficient at an instrument, which was a huge mistake because I could have been.

I can pick up the guitar and play it but I never really worked at it because there were so many good guitar players around. I mean, why bother? That was a big mistake.

RCM: While you wrote and co-wrote songs, more often than not you recorded outside material. As an interpreter of songs, what were the defining criteria for you that compelled you to say, “I want to record that song”?

Linda Ronstadt: It has to have a line in it, not the whole song but at least one line that just made me just go, “That’s exactly how I feel about my life” and sometimes it could be about the way a chord is voiced in the rhythm pattern. Sometimes it wouldn’t even be about the lyrics, sometimes it could just be about the chords. Jimmy Webb is so good at voicing chords in a way that just rips your stomach open.

I’d be listening to Jimmy, who I love so much, and think I’ve heard him play so many times and say “I’m not gonna cry this time because I’ve heard his music enough times, I’m kind of immune to it now”. And about four seconds later there’ll be something he’ll weave into a chord and I’ll start crying.

I’m not a crier; if someone broke my leg I’d probably spit in their eye but I wouldn’t cry or you could be really mean to me and say mean things to me but it wouldn’t make me cry. But if Jimmy plays one of those voicings or one of those ways that he turns a phrase I just burst into tears instantly.

Rosemary Clooney made me cry when she sang It Might As Well Be Spring on The Today Show; I just couldn’t stop crying.

I was in New Orleans watching The Today Show when Rosemary came on and sang that song and the weirdest thing is my brother Peter, who is the chief of police in Tucson, was thousands of miles away and watching the same show and he cried too. There are just certain things that seem to work in a universal way, maybe it’s genetic, I don’t know.

RCM: Speaking of Jimmy Webb, he penned the sublime Easy For You to Say, which you recorded for your album, Get Closer.

Linda Ronstadt: I love that song. It sounds really simple and it’s a very simple vocal. That’s the first record I worked on with George Massenburg and he taught me his method for overdubbing vocals. That’s one of the first vocals I recorded that wasn’t a live vocal. With that song I was given a chance to really work on it a little bit. The vocal on Easy For You to Say is all about texture and I could texture my voice to get a really full sound.

I was thinking about the sound Steely Dan got on their records—I’m not comparing myself to Steely Dan in any way, they’re much better than I am—but I was going for that smooth, uptown sound than the things I’d been fooling around with before. I was just working on texturing in with the track and the sound of the instruments like Steely Dan would do. By getting to sing it more than once (laughs) and getting to experiment with it I found those different textures that I wouldn’t ordinarily have found just by standing in front of the mic and just opening up and singing. So George and I considered Easy For You to Say our first vocal that we ever really did together.

RCM: In the new Eagles documentary The History of the Eagles, there’s great footage of Glenn Frey and Don Henley playing in your band.

Linda Ronstadt: It was hard to find musicians. First of all, nobody had any money in those days so we couldn’t pay them a lot. Because of that, you couldn’t hire those really good studio players to go on the road with you. And again, because those session players hadn’t come up on our road, they weren’t necessarily appropriate to our music as much as we admired them. A guy like Ricky Nelson or Elvis Presley could afford to hire James Burton. I couldn’t afford to hire someone like that.

So I was always looking for a drummer that wouldn’t just roll over me, that wouldn’t just play right on through the feeling and dynamics. My singing has a lot to do with dynamics and I like more delicate music sometimes ‘cause I’m a girl (laughs). At any rate I was looking for a drummer and I was looking for a whole band to go on the road. We walked through the Troubadour one night and there was this band on stage playing Silver Threads and Golden Needles and they were playing my version. (laughs) and they were playing it so well! (laughs)

I went, “Let’s just get them, they already know our music.” So that’s how we met Don (Henley) and we also hired their guitar player, Richard Bowden. I think at some point I hired Michael Bowden on bass – he was Richard’s cousin. He was a really sweet guy and he also worked for Emmylou (Harris). We used to call him “Ro-Tel” which was a brand of tomatoes. We called him that because he had a tomato red face.

John (Boylan) and I found Don at the same time. He had already spoken to Don because he’d approached him with songs that he had written that he wanted me to record. I didn’t hear a song that I thought was for me but I liked his playing.

Glenn (Frey) was my friend. He was the singing partner of JD Souther who was my boyfriend at the time and I was living with JD. I used to always play with Bernie Leadon who was a really good country rock player but he wasn’t available to go on the road because he was playing with the Flying Burrito Brothers. So I asked Glenn if he would play in my band; it was like, if I can’t get Bernie, let me ask Glenn. I didn’t think Glenn was necessarily the right guy but I knew he would make it more rock and roll.

I liked his playing and I thought he would be good but he wouldn’t be the same as Bernie because he didn’t know how to play all those bendy licks, and he didn’t need to learn them as it turned out. So I introduced Glenn to Don and they started working together. When they wanted to form a band John Boylan suggested Randy Meisner and I suggested they get Bernie Leadon. We said, “If you want to form a band come and work for me while you’re putting it together and you’ll have gigs. When you’re ready to sign a contract you can be your own band” and that’s what happened – and the Eagles were formed.

RCM: In that documentary Don Henley pays you a wonderful and well-deserved compliment. He said your version of Desperado was the definitive one.

Linda Ronstadt: Oh no, Don sang that better than I did. (laughs) My recording of it was awful! Oh my God, the arrangement was horrible. But again I learned how to sing that better on stage. On stage I did it with just a piano and I thought it worked a lot better.

RCM: Take us back to your time hanging out with Gram Parsons and Keith Richards and the song Wild Horses was being birthed. Gram got to it first with The Flying Burrito Brothers, even before The Stones and you also wanted to cut it.

Linda Ronstadt: Keith had just written Wild Horses and he’d already played it for Gram. He also played it that night we were all hanging out together. Gram had already asked him once if he could record it and Keith said, “Well, I’m not so sure. I don’t know if we’re gonna record it but we’ve gotta keep our songs for ourselves.” That night Gram said, “Oh, I really want that song, man. You’ve got so many songs, let me have that one!” I said to myself, he’s never gonna get that song. (laughs) I wanted that song too but I wasn’t gonna ask for it. I knew better. (laughs) As it turns out, Gram cut it first; he was persistent. (laughs)

RCM: In your book you state, “Being the Queen of rock in the ‘70s made me uneasy—I never felt defined by rock and roll”—can you expand on that?

Linda Ronstadt: Well, it was just one of the things I did – but it wasn’t what I did mainly.

When I felt I’d really come home was when I started working with Nelson Riddle and the Mexican band. Those were the two things I thought I did with the most authenticity, that and the work I did with Emmy. We were beating the same bushes and we really knew how to sing with each other.

Emmy makes anybody she sings with sound better. She gives everybody she sings with that incredibly prayerful quality.

I’ve heard her sing with Bob Dylan and I’ve heard her sing with Buddy Miller and I’ve heard her sing with Gram (Parsons) and I’ve heard her sing with me and with Dolly (Parton). She always does a fine job, there’s no getting around it. She has something that’s completely her own. She always shines and she doesn’t disappear into somebody else. I can tend to disappear more into somebody else because I can really blend with them. But Emmy creates a whole new thing, a whole new wing of the building. She doesn’t compete with the lead singer or try to outdo them. She doesn’t try to take it away; she just adds something. That’s really essential.

RCM: That brings up a point you made in the book where you felt that you were best suited to melodic ballads but had to compromise and record up-tempo rockers as well like Heatwave, How Do I Make You, Lies, Back in the U.S.A and It’s So Easy. But in listening to those songs, it sounds like your heart was in it.

Linda Ronstadt: It was, especially with a song like How Do I Make You. I got to do something a little bit more original for myself with that one as opposed to just trying to copy someone else as I did with songs like Heatwave and It’s So Easy. Don’t get me wrong, those kinds of songs were fun to do. But what I really luxuriated in, in terms of being able to find interesting textures in my voice and finding interesting melodies and beautiful harmonic atmospheres, were the standards. When I first started singing those it was just like a whole other world; I just went into another world. It was fabulous.

I felt like I had been completely let out of a box. I felt like there was something more I could do with my voice. I didn’t know what it was but it was always there whispering and saying, “There’s something you’re missing.” And when I started singing that stuff I went, “Oh my God, there it is, all the rest of my voice, it’s all there.”

RCM: You have a long history with Neil Young going back to the early ‘70s when you first met him. Share the experience of singing backgrounds with James Taylor on two of Neil’s signature songs, Heart of Gold and Old Man.

Linda Ronstadt: Those were the really early days when we were young and strong. We worked for two days on a Johnny Cash television show that was filmed in the Ryman Auditorium and everybody was at their best. I think I sang Long, Long Time. James (Taylor) had some new songs that he was performing and Neil sang Old Man. When we weren’t on stage singing we were watching each other. Those were all brand new songs we hadn’t heard before.

Neil [Young] said to James [Taylor] and I, “Come on over and let’s record. Will you come and sing some harmonies?” And I said “Sure, you bet I’ll be there.” (laughs)

Never mind we’d done two full days of filming with early calls to the set. That’s really hard for musicians to come in at nine o’clock in the morning and work long into the night. After we were finished filming we were still ready to go so we went into the studio with Neil and we sang all night long until dawn. It was winter and there was this beautiful snow storm when we came out. We were all sweaty from working in the studio. We were exhausted but we were so exhilarated ‘cause the music was beautiful. You can work for a long time on music you like. I can’t work for five minutes on music I don’t like, I just collapse. I just can’t do it. My voice just won’t do it. I have to go home and lie down. (laughs)

RCM: Years after you first heard it, you recorded Heart like a Wheel by Anna McGarrigle. You say “it rearranged my entire musical landscape”—how so?

Linda Ronstadt: What the McGarrigle’s do, for better or for worse, is art songs. Sometimes they make an attempt at what would be called contemporary pop music but they really write art songs. Someone who writes art songs as a form, like John Jacob Niles who wrote Black is the Colour (Of My True Loves Hair), The Lass From the Low Countree and Go Way From My Window. He was an American art songwriter who based things on traditional folk music but they were also more melodically sophisticated.

In the true sense of the word Gershwin and Rodgers and Hart are art songwriters too but they just happened to write songs that also succeeded as pop songs. They were writing in a pop song direction but they really came out with art songs. So did Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon, even though they worked in a popular genre they were completely art song composers.

Anna came out of that classical, folk music. She wrote that line, “You can’t call it soul, you’ll have to call it heart.” I mean that’s what the McGarrigle’s did. They weren’t afraid of female sentiment at all. We were all out there trying to get tough and funky. It was like Janis Joplin; we were trying to be ballsy. Janis was a wonderful singer and a wonderful artist and I love her. But there were other people who weren’t afraid of unabashed femininity and Janis wasn’t afraid of that either. A lot of what she was singing was a very female sentiment about getting her heart broken.

But we were all out there trying to out funk the guys.

Well, you know, art is not about competition. That’s what you have for horse races and sporting events. But competition is not a good thing in art. You have to try your best but don’t try to do the other guy in.

RCM: You’re No Good is one of your defining songs. It was a labored studio creation, especially on the part of Andrew Gold creating his majestic layered guitar solo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXnYunvwhiY

Linda Ronstadt: I was very very impressed with Peter Asher’s production on that song. Peter is a very very skilled and conscientious record producer. He’s really good at solving problems. Having produced records myself I really know what this is but I’m not as good as he is in terms of troubleshooting in advance, but I learned how to do a lot of that from him. If you’re gonna overdub something and lay a basic track down lots of times you’re just setting up problems for yourself later on.

Peter’s amazing at figuring out what’s eventually going to go there. He’s just a really really good record producer. The basic track of You’re No Good was a deliberate attempt to change the arrangement from the one I’d been doing onstage because I was tired of it and I thought we could do it better. I think I sang our original version on television once on The Midnight Special and that was the way we’d been doing it on stage. So we went into the studio and what happened was the guitar player Eddie Black started playing (imitates notes) and then Kenny Edwards put his bass part on there and echoed it playing it an octave lower. Andrew (Gold) was playing drums and then he overdubbed his piano part and then he overdubbed all his guitars.

So they started working on those guitar parts. I always had ideas about the arrangements but at some point I saw that they knew what they were doing. Andrew had something in mind and I wanted to hear what it was and he wanted to put it down. I went out to dinner for about an hour and half with Albert Brooks and I came back and they put this on and it was really good (laughs).

I really liked it and Albert at some point said, “I’m wondering why at some point this turns into a Beatle record?” He was right. It did sound like a Beatle record but it also sounded like something of ours that was band-driven. Peter Asher was not happy with Albert’s remark and he was kind of pissed off. While he was off scowling, our engineer, Val Garay, accidentally erased it. (laughs) It was very tense in there; it was not a good atmosphere.

Andrew was just exhausted from having done it but he was able to replicate it. Like I said, we were young in those days and we could stay up all night on the natch. We didn’t need drugs, we just needed music. (laughs)

RCM: Have your kids ever played you Van Halen’s cover of You’re No Good?

Linda Ronstadt: No, I’ve never heard it. That would be interesting to hear.

RCM: Let’s talk about 1980’s Mad Love album, which found you dipping into the New Wave zeitgeist of the time.

Linda Ronstadt: I wasn’t trying to do new wave songs; I was doing the songs that were available to me at the time. There were two new writers, Mark Goldenberg and Billy Steinberg. Mark wrote a few songs for the album including Justine, Mad Love and Cost of Love and he was in a band called The Cretones. Billy wrote How Do I Make You. They were two songwriters who were introduced to me by Wendy Waldman from Bryndle. She said, “I know these two great songwriters, you’ve got to hear them.”

I thought they were good songs. I didn’t think in terms of new wave or being trendy. They were younger guys writing these songs that I thought were good, so I recorded them. I recorded them with my band, most of the same guys that I’d been working with except we added “Kooch”, Danny Kortchmar from James Taylor’s band.

I thought they were good songs. I didn’t think in terms of new wave or being trendy. They were younger guys writing these songs that I thought were good, so I recorded them. I recorded them with my band, most of the same guys that I’d been working with except we added “Kooch”, Danny Kortchmar from James Taylor’s band.

He played fabulously on that album. Danny’s solo on Hurts So Bad is one of my favorite things on any of my recordings.

He’s a great player and I love his work; he’s got great arrangement ideas and he just gave that record a shape and a sound and an energy that was absolutely new for us. Danny had more to do with that record evolving the way it did than anybody. I finally learned how to sing by the time we did Mad Love. I was really starting to get it. Something was starting to click for me on that record. I don’t know if it was that successful of a record for me but it was when I started stepping out as a singer.

RCM: Russ Kunkel’s introductory drum roll on How Do I Make You ignites the song, informing it with incredible power and energy.

Linda Ronstadt: I agree. Russ got to stretch out a little bit by playing with Danny. Danny stepped into our band into that configuration and got different stuff from all the musicians who’d been playing with me for some time. It’s like singing, when I sing with Dolly or Emmy I sing in a different way. When we got a different guitar player in the band it just energized us and everybody sang and played differently.

RCM: I Can’t Let Go must have been a song you loved growing up?

Linda Ronstadt: Definitely. I was probably nineteen when the Hollies had that record out, I loved that song and I loved singing it because it was such a big reach. Again, I think I sang it better on stage than my version on Mad Love. That’s a really hard vocal, it’s so high. That song is very hard to sing. You’ve got to have a lot of energy in a certain part of your voice and there’s a lot of muscle. It’s a muscle song and I grew those muscles after I was out on the road for ten nights. After we’d been on the road for ten days I could really sing that song.

RCM: Mad Love showcases a wonderful array of songs—Look Out For My Love from Neil Young to three songs by Elvis Costello—Party Girl, Talking in the Dark, and Girls Talk. You’d also recorded Alison on your Living in the U.S.A. album.

Linda Ronstadt: I saw Elvis Costello play at one of those Hollywood clubs in the late ‘70s; I think it was at The Roxy. I particularly liked “Alison” because I had a girlfriend who had just gotten married and was on a rocky path in her life. She’s still a really dear friend and I sang that song for her. Then I did a few more Elvis Costello songs for Mad Love. I really loved Party Girl in particular. I’m sure to this day people have an impression of me as someone who’s sort of frivolous (recites lyrics)…”They say I’m nothing but a party girl.” That song really struck me. I loved singing that song. I used to sing that song until I’d be practically hallucinating.

The notes at the end are so high, (recites lyrics) …“I can give you anything but time”. I’d get oxygen deprivation (laughing) and start to see strange things during that ending. It would take me a little while to recover; I’d almost fall over. Party Girl is definitely a muscle song. (laughs)

RCM: At the time, your covers of those Elvis Costello ignited a controversy when he came out in the press and bashed your versions.

Linda Ronstadt: No, he didn’t like it. I heard later that he changed his mind about my versions and feels differently now. I think it’s hard for some artists who have a certain image of themselves, a certain image of who they are and where they fit in the musical hierarchy.

When you write a song you have to let that go because it assumes a life of its own and starts growing legs and arms.

I think that Elvis felt that any changes in those songs would be threatening to who he was and how he was perceived. I was very mainstream so again, it’s that party girl thing; people think I was frivolous so maybe Elvis thought I was frivolous. My musicianship was pretty suspicious for a long time. I don’t have the musicianship that Bonnie Raitt has so I’m sure that he was aware of that. He’s a really fine musician and I think that particular point did not escape him. (laughs) Hey, I would have agreed with him. I have great respect for Elvis Costello as a musician.

I’m really sad that I never got a chance to record a song of his that he wrote with Burt Bacharach called I Still Have That Other Girl because I lost my voice. I have Parkinson’s disease. I just found out about it eight months ago. I’ve had it for about twelve years. Parkinson’s takes your voice first, that’s where it shows up first. I was singing and struggling so much for years not knowing I had Parkinson’s disease. At the height of my ability to sing I think I could have sung I Still Have That Other Girl really well. I’d recorded another Burt Bacharach song, If Anyone Had a Heart and got a really nice letter from Burt saying he loved the way I sang it. It was really sweet.

RCM: Right around the same time as the Mad Love album, you recorded a lesser known duet with Mark Hudson on a song called Not Afraid to Love by the Hudson Brothers, which percolates with tons of energy and passion.

Linda Ronstadt: I haven’t heard that song since we recorded it. I didn’t even know that it was ever released. I thought The Hudson Brothers were really good. Mark was a really talented writer.

RCM: It appeared on the band’s Damn Those Kids album.

Linda Ronstadt: I’d like to hear that again.

RCM: In the book you make a surprising admission, “Between the ages of forty to fifty I did some of my best singing.”

Linda Ronstadt: My musicianship had really improved. After all those years of struggling I learned a lot of stuff. My ability to listen has also really improved. Working with George Massenburg refined my ability to hear. Working with Peter Asher gave me the ability to think in a much more organized and deliberate way. Peter was really good at that. I learned so much from Peter. So I had more tools in my tool box and I just learned how to do it better.

A lot of people like Jackson (Browne) and Jimmy Webb came to the table as young people so much better prepared than I ever was. They also had a lot more talent. I think either one of those guys has a lot more musical talent than I have. But it doesn’t matter because we’re not competing. (laughs) But at any rate, they were unusually gifted.

Same goes for Joni Mitchell and Bonnie Raitt. There’s a real example. Bonnie’s mother, Marjorie, was the piano accompanist for her father, John Raitt, who was a famous singer. Bonnie was born being her own accompanist (laughs). She was so loaded with talent. I saw her play at the Troubadour the first night she got to town. She got up and sat on a stool with her acoustic guitar and I thought, “Oh my God, another one of these girls with confessional songs.” We used to call them “therapy songs” and we were all kind of rolling our eyes. Then she started playing and we all just fell on the floor. It was one of the most incredible things I ever heard and still is. Bonnie is a really first-rate singer. Jennifer Warnes was also singing that night too and she’s also one of my all-time favorite singers. People used to say we sounded alike. She certainly wasn’t trying to copy me nor was I trying to copy her but we had similar sounding voices.

RCM: From your perspective, what makes a great singer?

Linda Ronstadt: There’s something extra. There’s an extra clarity. There’s an extra insistence and an extra sense of desperation and emergency that comes out of what they sing. It’s like the difference between a siren and a car horn. A siren is a whole other thing. You’ve just got to get this guy to the hospital before he dies of a heart attack. A car horn is “Please get out my way, I’m gonna turn left here.” I think great singers are sirens. They have an insistence and urgency.

RCM: You’ve covered a few songs by Brian Wilson. Can you characterize what makes him such a special writer?

Linda Ronstadt: I just love him and I love his work. I think there’s no filter on what he says. He’s such a pure person. It sounds patronizing to say that he’s childlike because he’s a grown man but it’s beyond that. There’s a purity about the way that he expresses himself that’s just so straightforward. He’s a true genius as a musician and I love the way that he writes harmonies and the way the words fit them in that pure straight forward way. He’s one of the few that were able to structure harmonies and voicings like the great classical masters.

His Gershwin album was beautiful but I like when he does his own stuff best.

A latter day song of his that I really wanted to sing was Love and Mercy. I also love I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times. I did In My Room for my Dedicated to the One I Love album and Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder) on my Winter Light record.

Don’t Talk is one of the most exquisite and beautifully constructed songs I’ve ever sung; the range and the melody came right out of the faerie bowers. In Ireland they say the faerie’s music was the most beautiful of all. They say the only reason the Irish music is so good is they got it from the faeries.

Don’t Talk is just a beautiful melody. I got to work with Brian when he sang background vocals on Adios and he showed me how he did it. He overdubbed himself on the same melody five times and it makes a chorus effect. He’d put a track down and I thought. “That’s out of tune.” He’d lean over to the board and he would mix it just right and it would turn into cream. It was perfectly in tune. I learned so much from Brian.

RCM: Is there one song that you regret not cutting, “the one that got away”?

Linda Ronstadt: I would’ve liked to have been able to record a version of the Elvis Costello/Burt Bacharach song, I’ve Still Got That Other Girl; that’s the one I really wished I could have sung. There’s also a song by Kate and Anna McGarrigle called Tell My Sister that I know I could have sung well. When I hear that song I go, “Oh man, why didn’t I record that?!”

RCM: Being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease prompted your retirement from touring and recording.

Linda Ronstadt: Yeah, I had to stop.

I couldn’t sing at all. It was like being a water skier and you’re skiing along on the top of the water and your skis are at the surface of the water and you’re floating along. But after I got Parkinson’s disease it was like I was skiing and my skis were still at the top of the water but I was underwater. I couldn’t steer anything. I couldn’t control pitch, and I couldn’t control texture.

There’s a huge amount of things you do when you sing. The way that your larynx makes sounds has to do with repetitive muscular movements. That’s what you really can’t do with Parkinson’s disease. It’s like I can start to walk and my legs will go the first couple of steps but then they don’t want to do it again. It’s like brushing your teeth; your hands will go up and down a couple of times and then they stop. So that’s what would happen with my voice. My voice would start to make sounds and then stop.

I knew there was something wrong and I kept going to the doctor. I was seeing the doctor who later saw Adele when she had her problem. He said, “There’s nothing wrong with your larynx”. In fact, he said that I had the best larynx he’d ever seen on a singer that had been using it as much as I had. (laughs) Somehow I managed to take care of it. I knew the cause of my not being able to sing wasn’t emotional. I knew it had to be physical. I knew it was muscular but I didn’t know I had Parkinson’s disease. It didn’t occur to me to go to a neurologist.

RCM: Is there anything you can do to strengthen your voice?

Linda Ronstadt: No. I did plenty of voice exercises. I just can’t do the voice exercises to strengthen my voice. There’s just no neurological juice. With Parkinson’s disease the brain cells that make dopamine are destroyed. So you can’t make the dopamine and you don’t get the neurological impulse to make the muscle.

It’s a drag. I’m glad I can still talk. It’s affected my speaking voice. I can’t be as expressive when speaking.

I’m trying to record the audio version of my book and it’s really hard. (laughs) I’m missing the whole top end of my speaking voice just like I was missing the whole top end of my singing voice. But it functions and I can get my point across. (laughs)

RCM: For a woman with self professed “simple dreams”, your life turned out to be much grander and richer than you ever imagined.

Linda Ronstadt: I never thought I’d have such a great life. It never occurred to me. (laughs) My little motto has always been “Shoemaker stick to your last.” A shoemaker makes a shoe using a device called a last so I stuck to my last.

I loved to sing and I tried to play music that reflected and told my story and made me feel passionate. That was my main ambition. And I was lucky that I had hits, which was surprising to me. (laughs)

Published on 2013/09/14

Holed away in his family’s music room, 18 year-old Brian Wilson, future music genius/visionary of The Beach Boys, is cocooned […]

Read More

Published on 2013/10/03

When rockers want to convey rage, frustration, pain or ecstasy, nothing works like an ear-splitting scream. Some rockers’ shrieks are […]

Read MoreMusic Books

Feature Everybody Loves Me By Leland Sklar

Check out more items

CDs/Vinyls/Box Sets

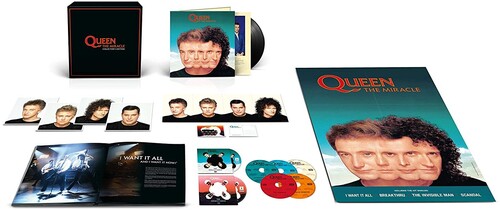

Feature The Miracle: Collector's Edition Box Set by Queen

Check out more items

T-shirts & Apparel

Feature Rolling Stores 60 Tongue Tee

Check out more items

Check out all Rock'N'Roll Items, CDs, Albums, Vinyls, Special Box Sets, T-shirts, and more... Latest News

Published on 2024/04/11

This month’s Top 11 entry finds Frank Mastropolo breaking down some of the best and most notable songs about dreams […]

Read More

Published on 2024/04/11

It’s fair to say that the debut album by The Smiths helped shape and define the genre we now know […]

Read More

Published on 2024/04/11

Collective Soul is ready to celebrate — and in recognition of the long-running alternative/pop band’s 30th anniversary in 2024, the […]

Read More

Published on 2024/04/11

Trey Anastasio and Phish will release Evolve, their first new studio album in over four years and 16th overall, on […]

Read More

Published on 2024/04/11

April 5 saw the release of the Dream EP, a new three-song EP from Dreamcar, the indie/pop project featuring No […]

Read More